Cities and regions for a blue economy

The blue economy can be a driver of sustainable economic development, but it is both subject and a contributor to climate change and environmental degradation.

Ocean health starts with freshwater health, but freshwater and ocean policies are disconnected, and water security is a blind spot in blue economy strategies.

Subnational governments are competent in policy areas that can improve water quality, such as water and sanitation, waste management and land use; and their investment responsibilities in grey and green infrastructure can foster resilience to growing water risks.

1. Understanding the blue economy

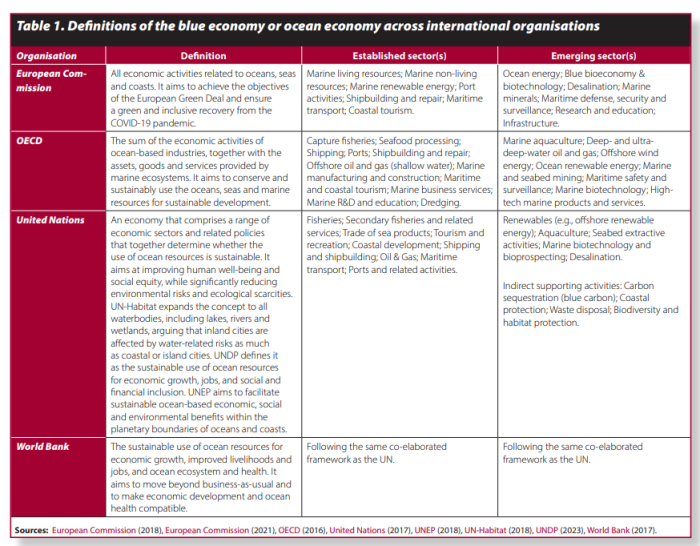

There is no single definition of blue, ocean or marine economy, which are often used. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) defines the ocean economy as “the sum of the economic activities of ocean-based industries, together with the assets, goods and services provided by marine ecosystems” (OECD, 2016), and divides ocean-based into “established” and “emerging” sectors. The classification of sectors differs from one framework to another: the EC and UN-World Bank propose a synthesised classification of 14 and 15 sectors respectively, while the OECD has a more detailed classification of 21 sectors (see table 1).

Considering only established sectors, the OECD conservatively valued the ocean economy at USD 1.5 trillion annually in 2010, accounting for around 2.5% of global GDP and 30 million direct job. In a business-as-usual scenario, in 2030, these sectors are anticipated to employ over 40 million people and to grow to more than USD 3 trillion, maintaining its share of 2.5% of total global GVA (Gross Value Added). Across almost all sectors, employment would grow faster than average for the world economy.

Economic growth and employment in many countries, regions and cities hinge upon water and ocean-based economic activities. For instance, Cambodia’s blue economy has been valued at USD 2.4 billion in 2015, accounting for around 16% of the country’s GDP and 2.4 million jobs (World Bank, 2023). In the state of California (United States), 1 in 9 jobs connects to port-related activity; in the state of Louisiana, the inland Port of South Louisiana ranks first in the country in terms of dry bulk cargo handled. In Barcelona (Spain), 15 000 people are employed in the blue economy, while in the region of Andalusia,the ocean economy accounts for around 10% of workers and 10.5% of GDP. However, given the range of differing definitions of the blue economy or ocean economy across countries, regions and cities, these estimates are challenging to compare – even within the same jurisdiction. For instance, the blue economy strategy of the city of Barcelona (Spain) highlights that estimates of the value of the blue economy are not comparable between the city, the region and the central government, as all three levels of government have different definitions of its scope.

The blue economy also includes the ecosystem services or non-market benefits provided by freshwater, coastal and marine ecosystems (e.g. natural river systems, wetlands, mangroves and coral reefs), such as carbon storage, flood protection, food provision and cultural values. Globally, ecosystem services are worth 1.5 times total GDP (OECD, 2021). In the European Union, an average EUR 400 billion of ecosystem services are generated on a 10km coastal zone (European Commission, 2023). Coral ecosystems alone contribute an estimated USD 172 billion per year to the world economy with benefits such as food and raw materials, water purification, recreation and biodiversity (OECD, 2022). Mangroves across several Indonesian regions provide valuable ecosystem services (e.g., coastal protection, climate regulation, raw materials provision) that contribute to human wellbeing, providing on average USD 15 000 and 50 000 per hectare per year in benefits in Java and Bali respectively (WWF, 2022). Investing in natural assets such as mangroves and coral reefs can be beneficial for tourism as well as flood protection, carbon capture and biodiversity. For instance, investing USD 1 in mangrove conservation and restoration can generate a financial, environmental and health benefit of USD 3-17 over a 30-year period (Ocean Panel, 2020).

The blue economy holds some of the keys to unlocking the energy transition. Water-based renewable energy (e.g. offshore wind power, floating solar panels or tidal energy) can power the clean energy transition; aquaculture solutions (e.g. oyster reefs) can mitigate coastal flood risks; and blue bioeconomy and biotechnology (e.g. seaweed farming) can capture carbon and nutrient pollution. The number of global ocean renewable energy inventions grew 7% annually on average between 2000 and 2019 (OECD, 2023). Offshore wind provided just 0.3% of global electricity supply in 2018, but it has the potential to generate more than 420 000 terawatt-hours per year worldwide, which represents 18 times current global electricity demand (OECD, 2022).

However, the blue economy can be an important source of carbon emissions, pollution and other environmental stressors. Maritime transport alone accounted for almost 3% of global CO2 emissions in 2018, and pollution from shipping (e.g. noise, untreated sewage and oil spills) affects both freshwater and marine habitats and biodiversity. Moreover, ghost fishing gear contributes to around 10% of plastic pollution in the ocean (Greenpeace, 2019), and resource-intensive activities such as tourism and coastal development can be large water abstractors and waste generators. For example, coastal tourism in Greece leads to a 26% increase in plastic waste influx, contributing to the 11 500 tonnes of plastic leaking into the Mediterranean every year, 28% of which stems from sea-based sources such as ghost fishing equipment (WWF, 2019). An international review of water use in tourism suggested that direct water use in tourism varied between 80 to 2000 litres per tourist per day, depending on the geographic location and the type of hotel (Gössling et al., 2012), significantly above the average consumption of 124 litres per day in Europe (EurEau, 2021).

Several blue economy strategies consider the importance of “greening” the blue economy (e.g. through decarbonisation or pollution mitigation) and preserving ocean and coastal ecosystems. For instance, Portugal’s National Ocean Strategy (2021-2030) has 9 strategic goals including decarbonisation, supporting the country’s efforts to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 while improving the health of marine and coastal ecosystems. At subnational level, the state of Washington’s (US) Maritime Blue Strategy (2022) aims to accelerate the decarbonisation of its maritime industry through technological innovations, infrastructure, and incentives to facilitate local, coastal, and international maritime operations (e.g. modernisation of state and regional ferries and shore-side infrastructure with cleaner low-carbon fuels). Similarly, the Port of Vigo’s (Spain) Blue Growth Plan (2021-2027) has set a target to become a carbon sink by 2030 by increasing renewable energy use in port operations and business activities, using cleaner alternative fuels such as hydrogen on ships, and fostering seabed regeneration and CO2 sequestration through artificial reefs, for instance.

Recognising the potential of the blue economy for sustainable economic development and the need to protect coastal and marine ecosystems, a growing number of international declarations and frameworks aim to boost its contribution to sustainable development agendas. Against the backdrop of the Paris Agreement on climate, the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (2015) and the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030), the blue economy discussion has seen:

• Statements of intent making the blue economy a priority for sustainable economic development at global and regional levels, with the Nairobi Statement of Intent on Advancing the Global Sustainable Blue Economy (2018), the Jakarta Declaration on Blue Economy (2017) and the Communication on a new approach for a sustainable blue economy in the European Union (2021).

• Guiding principles for a sustainable blue economy including the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 14 – Life below water), UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEPFI) Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles and the Chennai High-Level Principles on Sustainable and Resilient Blue/Ocean-based Economy (2023) adopted by members of the G20.

• International treaties aiming to protect the ocean from existing and emerging stressors, such as the ongoing meetings of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee established to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment (2022-2024), and the Treaty on the High Seas adopted by the UN General Assembly’s Intergovernmental Conference on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (2023).

• However, few of these national strategies, declarations and frameworks recognise subnational governments’ crucial role in marine and freshwater conservation, water-related risk prevention and the blue economy. Recognising that subnational governments have a key but often underexploited role to play in unleashing the potential of a sustainable blue economy, the OECD programme on Cities and Regions for a Blue Economy aims to shed light on how a territorial approach to the blue economy can leverage place-based policies and subnational government competences to accelerate efforts towards sustainable blue economies.

2. Water security as a condition for thriving blue economies

Shedding light on the link between the blue economy and water security

Climate change magnifies water risks, which the OECD (n.d.) defines as “the risk of too much, too little, too polluted water and disruption to freshwater systems”, by affecting the water cycle: more than 90% of natural disasters are related to water (UNEP, n.d.). Achieving water security means maintaining acceptable levels of these four water risks (OECD, 2013). Rooted in seas, coasts, rivers or lakes, blue economy sectors are particularly vulnerable to water-related risks in freshwater, coastal and marine environments, which are inextricably linked to one another. For instance, 72% of fish and invertebrate species representing 77% of total catch are estimated to be linked to river flows at some point in their life cycle (Broadley et al., 2022).

Water risks can have severe economic impacts, especially in cities, which generate around 60% of GDP and employment in OECD countries. For example, a drought can cost up to 6% of GDP per annum by 2050 (World Bank, 2016), reduce a city’s economic growth by up to 12% (Zaveri et al., 2021) and damage buildings and infrastructure due to the expansion and retraction of soils and land subsidence. Droughts, floods, and storms could wipe USD 5.6 trillion from global GDP between 2022 and 2050 (Aquanomics, 2023). “Too little” water can make rivers too shallow for fluvial transport or energy generation, with ripple effects beyond the blue economy. Shipping on the Rhine river was down 27% in 2018 due to low water levels, leading German industrial production to fall by 1.5%, and the production of chemicals and pharmaceuticals to drop by 10% for three months (OECD, 2023). Since mid-August, the persistent drought in the Panama Canal region has compelled authorities to impose traffic restrictions, resulting in a bottleneck of more than 100 large vessels transporting commodities thought to be worth billions of dollars (Earth.org, 2023). The Panama Canal anticipates a reduction of approximately USD 200 million in revenue during its upcoming fiscal year due to these crossing restrictions (Reuters, 2023).

Floods, sea level rise and coastal erosion can disrupt marine and freshwater ecosystems while damaging waterfront infrastructure and assets such as ports and shipyards. With almost 11% of the global population living in Low Elevation Coastal Zones in 2020 (IPCC, 2022), sea level rise is projected to affect 800 million people living in one of the 570 cities exposed to sea level rise of at least 0.5 metre (C40 Cities, 2018). In the state of California (US), which has the largest ocean economy in the country valued at over USD 44 billion annually, USD 8-10 billion of existing property value is likely to be underwater by 2050, and an additional USD 6-10 billion to be at risk during high tides. In the San Francisco Bay Area alone, 104 000 existing jobs and the creation of 85 000 new jobs could be threatened by sea-level rise in the next 40-100 years (Ocean & Climate Platform, 2023).

Water pollution from land-based sources can wreak havoc on both freshwater and marine ecosystems. Currently, about 60% of plastic marine debris is estimated to originate from urban centres, and around 80% of marine pollution comes from land-based sources such as untreated sewage (UNEP, 2021). The cost of water pollution exceeds billions of US dollars annually in OECD countries (OECD, 2017): for instance, in the US, the loss in lakefront property values due to nutrient pollution, which causes eutrophication and can trigger toxic algal blooms, has been estimated to cost between USD 300 million and USD 2.8 billion. Plastic pollution affects rivers and oceans alike: to date, 30 mega tonnes (Mt) of plastics have accumulated oceans, but more than triple that amount – 109 Mt – has piled up in rivers (OECD, 2022). Plastic pollution alone costs fisheries in the Gulf of Thailand USD 23 million per year (IUCN, 2020) and around EUR 13 million per year to the Scottish fishing industry (KIMO, 2010).

Exacerbated by climate change, phenomena such as acidification, freshwater and marine heatwaves adversely impact fisheries, tourism and the ecosystem services provided by waterbodies (e.g. recreation, carbon capture and water purification). Marine heatwaves, whose frequency has doubled since the 1980s, can cause long-lasting or irreversible damage to many marine species, leading to mass mortality events and ultimately threating food security (OCP, 2023). Ocean warming and acidification cause damage to coral reefs (e.g. bleaching), which increases coastal flood risk and dampens reef-related tourism. In the state of Queensland (Australia), for example, the bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef could cause the loss of 1 million visitors to the region each year, equivalent to at least AUD 1 billion in tourism spending and 10 000 jobs (Australian Climate Council, 2017). In the state of Florida (US), coral reef degradation could increase the coastal flood risk to more than 7 300 people, costing an additional USD 823 million every year (Storlazzi et al., 2023).

Water security in blue economy policy

Despite the intrinsic link between water resilience and economic resilience, water security is generally a blind spot of national and subnational blue economy strategies, which tend to focus on boosting blue economy growth. Nevertheless, some blue economy strategies make the connection between the blue economy and water security. For instance, the US Blue Economy Strategic Plan (2021) piloted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) aims to increase the resilience of the country’s coasts and oceans as well as the Great Lakes communities. The Blue Economy Vision for Scotland (2022) insists that the country’s marine and inter-linked freshwater and coastal environments need to be sustainably managed, restored and resilient to climate change.

Protecting and restoring the coastal and marine environment is considered in some strategies, but the resilience of coastal and marine environments and related economic activities is not often linked to freshwater resilience. This may be due to most blue economy strategies being led by government departments responsible for economic development or oceans, and freshwater and oceans often belonging to separate departments. Globally, government entities responsible for ocean health are often not the decision-makers or regulators of many of the activities that threaten its well-being in freshwater and on land (SIWI, 2020). The IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (2019) highlights that water-related governance arrangements (e.g., marine protected areas, spatial plans and water management systems) are often too fragmented across administrative boundaries and sectors to provide integrated responses to the increasing and cascading risks from climate-related changes in the ocean and/or cryosphere. A counter-example is the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management, a newly created government entity responsible for protecting, restoring and ensuring the sustainable use of freshwater and marine resources, including fisheries management. Similarly, one of the departmental mandates of Fisheries and Oceans Canada is to protect oceans, freshwater and aquatic ecosystems through science, in collaboration with indigenous communities.

3. The case for resilient, inclusive, sustainable and circular (RISC-proof) blue economies: a comprehensive framework

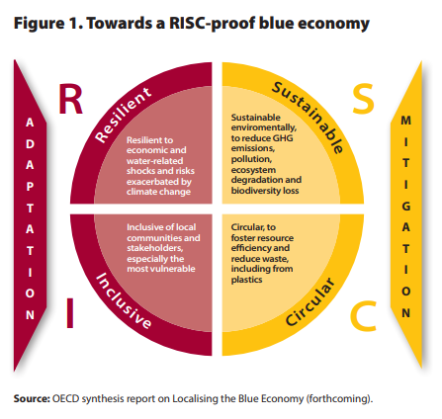

The blue economy has both a direct (e.g. pollution) and indirect (e.g. climate change) impact on freshwater, coastal and marine ecosystems. The literature reveals the dual dynamics at play. On the one hand, the blue economy is increasingly vulnerable to climate change, which mainly manifests through disruptions to the water cycle. This underscores the need for a blue economy that is resilient to climate change and inclusive of local communities adversely affected by water-related risks. On the other hand, as a potentially significant source of carbon emissions and pollution, blue economies should embrace sustainability by striking a balance between economic growth and environmental preservation while integrating circularity to minimise waste and promote resource efficiency.

The OECD programme on Cities and Regions for a Blue Economy therefore suggests a framework encapsulating four dimensions that national and subnational governments ought to consider in the context of the blue economy: resilience, inclusiveness, sustainability and circularity (Figure 1).

The Programme suggests that governments should aim for a blue economy that is:

• Resilient to water-related risks exacerbated by climate change by using tools to ensure water security (e.g. disaster risk reduction, nature-based solutions, water pollution prevention, etc.). For example, in the French overseas archipelago of Guadeloupe, 400 companies in the fields of commerce, services and fishing experienced a combined revenue loss of nearly EUR 5 million in the first half of 2015 alone as a result of sargassum proliferation (CCI-IG, 2016). To tackle this issue, Guadeloupe joined the Sargassum Algae Cooperation Programme, which aims to strengthen the resilience of Caribbean territories by facilitating knowledge-sharing for sargassum management and valuation (e.g. to decontaminate agricultural soils loaded with pesticides).

• Inclusive of local communities and stakeholders through engagement, employment opportunities in the blue economy and the protection of the most vulnerable (e.g. those living in informal settlements or sub-standard housing) from water risks. For example, the 2018 Maritime Strategy of Catalonia (Spain) prioritises community-led fishing management structures based on co-management, where each stakeholder interested in achieving sustainable fishing can participate with equal decision-making power and take on shared responsibilities in the co-management process. The strategy also aims to increase the share of women employed in fisheries and aquaculture, as they currently make up just 2.6% of the Catalan workforce in the sector. The Seine-Normandie Water Agency (France) organised Water Stakeholder Forums in 2022 to discuss the implementation of the Water Development and Management Plan (SDAGE) for 2022-2027 with around 900 local stakeholders. The Plan includes measures to protect and restore wetlands while limiting new coastal developments; collect and treat wastewater discharges from ports, boats, and campsites; and anticipate the need for drinking water in areas of demographic and tourist development to control water abstraction and prevent saline intrusion.

• Sustainable environmentally, by limiting greenhouse gas emissions and pollution from blue economy sectors, sustainably managing coastal, marine and freshwater resources (e.g. fish and minerals) and conserving freshwater, coastal and marine ecosystems (e.g. wetlands). To promote sustainability, the Port of Seattle’s (US) Smith Cove Blue Carbon Pilot Project is restoring underwater habitats and biodiversity, particularly with oysters, to sequester carbon, filter water and mitigate flood risk. In the port of Valencia (Spain), CO2 emissions dropped 30% between 2008 and 2019 despite activity growing 42%, due to initiatives such as fleet replacement with hybrid and electric vehicles, the adoption of cleaner fuels like liquid natural gas (LNG) and hydrogen, and the upgrade of lighting systems in port areas.

• Circular, to foster resource efficiency and reduce waste, by using resources efficiently and keeping resources in use for as long as possible, preventing waste and transforming waste and/or by-products into resources. As part of a circular economy, the city of Rotterdam, Netherlands has created Blue City in 2019, a platform and accelerator for circular entrepreneurs that contribute to reducing waste and pollution by reusing existing products and materials. The nautical and naval industries of the region of New Aquitaine (France) and the state of Washington (US) carry out repair activities to maintain existing commercial and recreational vessels, thus keeping existing resources in use for as long as possible.

To foster resilient, inclusive, sustainable and circular blue economies, the preliminary results of the OECD Programme on Cities and Regions for a Blue Economy point to three emerging priorities.

First, better explore the role of subnational governments. Few of the mounting international declarations and agreements and national strategies related to oceans and the blue economy recognise the importance of a localised approach that leverages the role of place-based solutions, even though many of the most powerful tools for water security – land use, spatial planning, waste and water management – are in the hands of subnational governments. Cities and regions can also invest in infrastructure and nature-based solutions to mitigate flood risk and improve the resilience of local economies. They are also guardians of local culture and traditions linked to water-related economic activities, which can help ensure that solutions win the approval and active support of local communities. More broadly, cities and regions are crucial to achieving the SDGs: at least 105 of the 169 SDG targets will not be achieved without proper engagement and co-ordination with local and regional governments (OECD, 2020).

Second, foster policy coherence across oceans, freshwater and land. Ocean and freshwater decision-making are often disconnected from one another, even though healthy oceans start with healthy freshwater. If freshwater and land do not have a seat at the ocean decision-making table, the ocean’s main environmental stressors risk being overlooked. Similarly, coastal and inland cities cannot be disconnected from the basins they sit in. Basin organisations, which are set up by political authorities, or in response to stakeholder demands, deal with water resource management issues in river basins, lake basins, or across important aquifers. They can help cities and regions tackle the risks of “too much”, “too little” and “too polluted” water and unlock the potential of the blue economy through engaging stakeholders across catchments, planning, coordination, data collection and monitoring.

Third, create the right enabling environment. For a resilient, inclusive, sustainable and circular blue economy to thrive in cities and regions, technical solutions are not enough. Subnational governments need to find new funding mechanisms to support marine and freshwater protection; set sound incentives and frameworks to catalyse investments; develop partnerships with private actors, community organisations, cooperatives, think tanks and research institutes and stimulate blue entrepreneurship; create synergies across policies such as spatial planning, waste, energy, transport that affect the quantity and quality of water; and foster dialogue between scientists and policy makers, amongst others. These solutions are outlined in the Multi-Stakeholder Pledge on Localising the Blue Economy developed by the OECD in partnership with Atlantic Cities, International Association of Cities and Ports (AIVP), ICLEI - Local Governments for Sustainability, International Network of Basin Organisations (INBO), Ocean & Climate Platform, Resilient Cities Network, and United Cities and Local Governments Africa (UCLG-Africa).

4. Conclusion

The blue economy is gaining traction as a means of combining economic growth with environmental protection, health and wellbeing. Considered as the sum of economic activities taking places in oceans, coasts, rivers and lakes, the blue economy can be a powerful driver of sustainable development in coastal and inland cities, regions and countries. However, the blue economy is both subject and a contributor to climate change, water risks and environmental degradation. This raises the need for a blue economy that is resilient to climate change; inclusive of local communities; sustainable, by balancing economic growth with environmental preservation; and circular, to minimise waste and promote resource efficiency. A review of the existing literature, including international declarations and agreements, national and subnational strategies related to the ocean and blue economy, reveals that water security and subnational governments are often absent from considerations. Further research may focus on:

• Elucidating the link between freshwater and marine ecosystems and the blue economy;

• Highlighting how the blue economy can both magnify water risks (e.g. through unsustainable fishing practices and coastal development) and mitigate them (e.g. through sustainable aquaculture and ecosystem-based approaches to coastal management);

• Documenting how “territorialising” the blue economy, i.e. tailoring blue economy strategies and policies to local and regional needs, marine and freshwater ecosystems, cultural practices and economic priorities, can make measures more effective and integrated, with co-benefits for other policy areas (e.g. climate mitigation, climate adaptation and water security);

• Better understanding roles and responsibilities across levels of government in managing ocean, coastal and freshwater resources based on institutional frameworks, capacities and priorities.

Authors:

Oriana Romano, Head of Unit, Water Governance, Blue and Circular Economy, OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities (CFE)

Juliette Lassman, Policy Analyst, Water Governance, Blue and Circular Economy, OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities (CFE)

Georges Laimé, Junior Policy Analyst, Water Governance, Blue and Circular Economy, OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities (CFE)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24241/NotesInt.2023/296/en

The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the OECD or of its member countries

All the publications express the opinions of their individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CIDOB as an institution.