Escalating rivalry between Algeria and Morocco closes the Maghreb-Europe pipeline

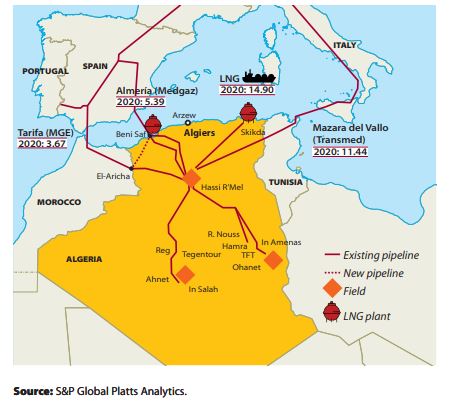

A 1,600-kilometre pipeline which lies empty is an unusual sight. All the more so when it links two continents (Africa and Europe) and four countries (Algeria, Morocco, Spain and Portugal). Building its underwater section under the Strait of Gibraltar was a technical feat of the Italian company Saipem which, in the early 1980s, had conceived and constructed the first underwater gas pipeline in the world linking Tunisia and Italy, under the Strait of Sicily. The flow of gas in the Enrico Mattei pipeline which carries Algerian gas to Italy through Tunisia has never been interrupted since 1983. Nor have the exports of Algerian liquefied natural gas (LNG) - through a revolutionary process developed by Shell in Arzew in the early 1960s. The first ever shipment of LNG left Arzew for Canvey Island in the Thames in 1964. The crisis in the Maghreb has parallels with the recurring tensions between Russia and Ukraine which pushed Russia to build the Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines to avoid depending on transit through Ukraine. Except that in Algeria’s case, the Medgaz which links Algeria directly to Spain via the Mediterranean Sea already exists. However, as from 1 November, Algerian gas is no longer exported to and through Morocco, through the Maghreb-Europe Gas Pipeline (also known as Pere Duran Farell pipeline) which has been up and running since 1996. The gas sales agreement between Algeria and Morocco expired on the same date as the transit contracts linking Spain and Portugal to Morocco, as well as Algeria’s gas sales contracts via the Maghreb-Europe Gas Pipeline (MGE).

As Russia blows hot and cold over a possible increase in its gas deliveries to the EU, as neither Saudi Arabia nor Russia have done anything to promote an increase in the supply of oil and gas that could have helped to curb the rise in prices of these hydrocarbons, particularly gas, the Spanish foreign minister has received “the guarantee of gas supply from Algeria to Spain, as well as the commitment to satisfy Spanish demand”. Thus, in this context, Spain has, since late summer, been receiving a greater volume of gas through the two lines supplying it from Algeria than the contractual volume. Sonatrach, Algeria state oil and gas company, might be able to export the equivalent of 2 billion cubic meters (bcm)/annum of additional LNG to Spain. Algeria could also increase it gas exports to Italy via the Transmed gasline if Italy and Spain can find a way of swapping gas.

As they try to maximise their gas and LNG contracts with other suppliers, Spain and Portugal face a very tight market, but at least Spain has a 60 bcm/annum regasification capacity which is way above its consumption of 32 bcm in 2019. Petrostrategies calculates that the closure of the TransMed could cost Spain as much as $4 bn/annum, though Algeria might take their long-standing relationship with the country into account and sell LNG to the latter more cheaply than is available on the spot market. The cost of the closure to Portugal is estimated by the same source to be about $2.2 bn/annum. Morocco for its part will have to fall back on other energy sources, though it has asked Spain to consider setting up a reverse-flow system on the MGE. Such a system requires time and money to set up. The Alawi kingdom will have to increase output from its coal-fired plants and, if it is available, import more electricity from Spain.

The MGE has a capacity of 13 bcm but, in 2019, only 7 bcm was passing through the pipeline, of which 2.5 bcm destined to Portugal. Medgaz will have a capacity of 10.3 bcm by the end of the year but an estimated 8 bcm is already allocated to contracts with several buyers supplying Spain, thus leaving only 2.3 bcm available to supply the Iberian Peninsula via Medgaz. Algerian gas exports to Spain account for a fluctuating 20%-50% of that country’s import needs.

Mistrust between Algeria and Morocco runs deep

In a note circulated among the group of non-aligned on 16 July, the Moroccan embassy to the United Nations (UN) wrote that “the valiant people of the Kabyle region” of Algeria deserve to fully enjoy their “right to self-determination”. A month later, paying the first official visit to Morocco by an Israeli foreign minister, Yair Lapid discussed with his Moroccan counterpart their “concern about the role played by Algeria in the region” notably its close links with Iran. The economic fallout of Morocco’s recent hardball diplomacy with Germany, Spain and now Algeria is now clear for all to see. The political crisis was thus not a bolt out of the blue which raises the question of whyMorocco and the two Iberian countries did nothing to avoid a looming gas shortage “by concluding a transit agreement”. The oil and gas weekly Petrostrategies pointed out a month ago that, had this been done,“Algeria would then have renewed its gas contracts to Morocco, Spain and Portugal. Despite the eruption of the political crisis, Algiers would have been forced to honour its commitments in order to maintain its credibility as a reliable supplier”. Algeria has scrupulously honoured its foreign gas contracts ever since it started exporting gas, in LNG form, to the United Kingdom in 1964 and by pipeline to Italy in 1983.

As the two north African countries turn their back on one another the high hopes of industrial cooperation which existed in 1996 have been dashed and with them the opportunity of creating a chemical Maghreb which would have inserted the region more closely into world trade. Hundreds of thousands of potential jobs will go missing in a region where youth unemployment and poverty are high, and rising. The pipeline could have brought greater wealth and stability. It has come to symbolise the lack of leadership which has bedevilled North Africa for decades. Algerian and Moroccan rulers have been incapable of building any form of regional economic cooperation that would have given younger people hope of a better future and the Maghreb a voice on the world stage.

The mistrust between Algeria and Morocco goes back nearly six decades. Competition to be the leading regional power is at the heart of this bitter rivalry which has prevented broader economic cooperation between North African countries from Tunisia to Mauretania. Failure to open borders and encourage trade and investment across the Maghreb has shaved at least 2 percentage points off growth, encouraged the flight of capital, and denied a region where unemployment is high massive amounts of investment, both private and public, national and international. Neither the EU nor the United States has been able - critics would argue, willing, to bring the two countries closer.

The Western Sahara is, in diplomatic terms, a frozen conflict. When the former US Secretary of State, James Baker, headed the UN mission on the Western Sahara at the turn of the century, he acknowledged that “the UN can only be as effective as its member states… the member states don’t want to solve it, so it is not going to be solved”. Seventeen years after he made that statement, nothing much has changed. The international status of the former Spanish colony remains in limbo but Morocco is unlikely to relinquish its claim. The US recognition of Morocco’s sovereignty over the Western Sahara announced by Donald Trump just before he left office “makes no sense” and has “a negative impact on the West Saharan question” according to Robert Malley who, on 21 January 2021 relinquished the presidency of the International Crisis Group to become the special US envoyfor Iran.

Europe never engaged strategically with North Africa

The empty pipeline also speaks an EU unable to think strategically about a region which is important for its security because its member states are divided. The revolts which spread across the Arab lands in 2011, the more active role played by Turkey and certain middle East monarchies, let alone China, in the Mediterranean have been met, in the Maghreb, by a failure of Europe’s political imagination. Europe has failed to live up to the challenge of its turbulent frontiers and the arc of crisis which, for a quarter of a century, spread from the Baltic states to Morocco. The EU and the US have allowed Russia to build up its military assets by accumulating strategic and tactical mistakes in Iraq, Libya and Syria. The West has indulged in wars of choice which have destabilised a region bedevilled by long-standing domestic and regional conflicts.

One of the key reasons the EU never engaged with North Africa is that it never offered the region the kind of economic integration that Germany did to its Eastern European hinterland. By heavily investing in industrial sites in the East, and fully leveraging its comparative advantages, Germany made it a “verlängerte werkbank” (a workshop extended to the East).

In the late 1990s, the EU had taken to portraying itself as a “normative” power. While the Union lacked the attributes of traditional military superpower it could project global leadership by promoting such norms as democracy, rule of law, human rights and social solidarity. Such lofty aspirations however never formed the real basis of German, or for that matter French foreign policy. The German decision to go ahead with Nord Stream 2 was inspired by “wandel durch handel” (change through trade). North Africa and Eastern Europe do not share the same historical or economic account but Northern Mediterranean countries might and should have followed Germany’s example vis a vis their Maghrebi counterpart. Yet, it was never the intention of France, the key player in this game, to offer its former colonies a partnership in industrial development. This speaks of a failure of France’s political imagination.

The EU promoted its “normative” power in North Africa but never any industrial policy which might have benefited Maghreb countries as a whole. In such circumstances, the enhanced economic cooperation offered by the Barcelona Process in 1995 failed to live up to its promise because it never went beyond dressing up existing mercantilist practises, particularly those France enjoyed, in new garb. It failed to address the opportunities offered by oil and gas, phosphates and fertilisers and the broader chemicals industry at a time when the European chemical landscape was vanishing and being remodelled in a radical way. The EU failed to spot the rapidly growing demand for fertiliser that the relentless increase in world food consumption would require.

Never did EU leaders, or north African ones for that matter, consider the opportunities of a “chemical Maghreb”, where the joint use of phosphates – of which Morocco has huge reserves, gas and sulphur – which Algeria enjoys in abundance to which could be added ammonia, to take advantage of the fast migration of chemical industries from northern Europe to the southern hemisphere. Chemicals such as vitamins, colouring agents, industrial dyes, to quote but a few, have left Europe. The Gulf has built a powerful chemical industry, not so Algeria and Morocco. Algeria derives 95% of its export income from oil and gas, unchanged from 40 years ago, a symbol of failed economic policy. Morocco in contrast has through its nimble phosphate monopoly, OCP Group, built up a network of joint ventures across Africa and in Brazil. Fertilisers derived from phosphates have been leveraged using management techniques worthy of any well managed international company.

The EU’s lack of deep economic engagement with the Maghreb is also the consequence of France’s stubborn defence of its interests in its former colonies. The emergence of new outside actors such as China, Turkey, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and older players such as Russia has allowed often precarious north African ruling elites to leverage new sources of military, trade and political ties to reduce their overdependence on Europe. So far, US has not disengaged from the region. It is playing an active role in Tunisia, is engaged with Algeria in guaranteeing the security of Tunisia’s borders with Libya, and does not appears averse to Algerian security forces playing a greater role in Mali as France slowly disengages from its military commitment there.

Sonatrach is a wounded giant

Sonatrach meanwhile has been through so many scandals and corruption trials over ten years that it is the shadow of its former self. It is a testimony to the skills of its engineers that the proud company of the 80s and 90s has not been destroyed. Export earnings grew by 45% to $12.6bn during the first five months of 2021 over the corresponding period last year, so that the entire year can be expected to yield $35bn. In terms of investments and projects, the company which claims to have made 18 new discoveries last year has updated the volumes of hydrocarbons in place, to two and a half times what they were in 2019. This statistical sleight of hand fools no one in Algeria where falsifying statistics, notably on hard currency reserves, has become the norm in recent years. Nonetheless, Sonatrach’s decision to revive its policy of forming partnerships with foreign companies following the adoption of a new law on hydrocarbons in 2019 has given it a new advantage.

Sonatrach stopped importing diesel and gasoline in 2020, and started exporting them for the first time in ten years but this had more to do with collapsing demand in Algeria due to Covid-19 that anything else. Imports will increase again as projects to build a new refinery and a polypropylene plant in Hassi Messaoud, in collaboration with TotalEnergies and with Turkey are just that: projects on which building has not yet started. Over the 2020-2025 period, capital expenditure is expected to total $40bn, 51% of which will be in its national currency. An often overlooked point is that Algeria holds the third largest unconventional gas reserves in the world. Fears are widespread in Algeria today that developing such reserves could endanger the deep Saharan aquifers but technology is moving fast. In a few years’ time, far safer methods of extraction might be available.

Away from the hydrocarbons sector, the country’s economy, with a few exceptions, is in free fall. The State appears to be incapable of enacting deep economic reforms. It tried to do so thirty years ago but internal opposition got the better of the reformers. Political turmoil has not prevented Algeria being a very reliable providers of gas to all its foreign partners but joint ventures outside the exploration and production of hydrocarbons are few and far between, ruled out by a Jurassic parc regulatory policy and the endless game of managerial game of chairs which comes as a result of recent political turmoil.

Will the Maghreb decouple from Europe?

The closure of the Maghreb-Europe pipeline will further encourage the economic decoupling of countries on the two shores of the Western Mediterranean. Turkey and China are both developing their trade and investment ties in the region while Morocco is building new ones across west Africa and, in OCP’s case, across the world. Russia’s military presence is meanwhile growing in North Africa and the Sahel countries while relations between France and Algeria are going through their worse crisis in decades. As France draws down its forces in Mali, Algeria will step up its presence. As the tectonic plates move in the region, the EU has no new ideas, let alone policies to offer. Might Chinese companies integrate the Maghreb in the years ahead? Such an outcome is less far-fetched that it might appear but the onus will be on North African countries. Europe might even be tempted by some kind of triangular perspective. The EU’s incapacity to think strategically about North West Africa and the wider Mediterranean region points to its influence declining further as we move into the second quarter of the 21st century.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24241/NotesInt.2021/260/en

E-ISSN: 2013-4428