China and the Global South: trade, investment and rescue loans

The Global South occupies an increasingly important place in China’s trade and investment flows. This grouping of countries is allowing China to diversify its imports, secure new markets and reduce its vulnerabilities as it engages in a strategic competition with the West. Currently, three out of every four dollars that China invests go to countries participating in the Belt and Road Initiative, where the Asian giant is emerging as a funding alternative in times of crisis. This greater presence brings greater geopolitical influence, but it is not without its challenges.

The Global South: a more positive view of China’s trade boom

At the end of the 1970s, China embarked on a series of economic reforms that would take its share of global goods exports from barely 1% to 15% in the space of 40 years. This was to the detriment of the exports of Europe, the United States and Japan, which experienced severe industrial decline. The defining moment of this process was China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. It was a milestone that allowed the country to leverage its manufacturing power and integrate into the global value chains ushered in by globalisation.

The structure of China’s trade remained virtually unchanged from early 1990 to 2001, a period in which high-income countries accounted for 70% of its commercial dealings. Today, however, these countries “only” represent 50% of Chinese trade, while the Global South has hit 40%1, thanks to greater economic growth and China’s readiness to diversify its transactions and reduce its reliance on the West2.

By region, Asia accounts for nearly half of China’s trade activity. The Global South countries located in Southeast Asia are particularly important (15% of the trade) because they are close at hand and integrated into the value chains of Chinese products. South America, the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa, meanwhile, account for over 20% of China’s imports, largely thanks to their natural resources.

But these intense trade relations have spawned major economic dependencies, especially for certain countries in Central and Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands3. Turkmenistan and Timor-Leste, for example, rely on China as the destination for 70% and 60% of their exports, respectively. In general, raw materials exporting countries are more dependent on China. There are regions, however, like North Africa and the Middle East, whose countries’ trade is more diversified and where China’s economic influence is more limited.

This trade growth is without precedent in recent history. It was possible thanks to the nature of the Chinese economy and policies that kept manufacturing costs low, but which caused friction with the West. This was especially true of the granting of state subsidies and restrictions on foreign investment, measures that were taken to protect its companies from competition and on national security grounds. China also received particular criticism for alleged appropriation of intellectual property and currency manipulation to support its exports. In addition, the West sees China’s trade surplus as a weakness and Chinese dominance of key technologies for the green and digital transitions raises fears that the trade imbalance will become permanent and jeopardise supply security.

From the Global South’s viewpoint, however, the perception and impact of China’s commercial rise is very different. Most of these economies are net importers of goods and they have benefited from greater affordability of global consumer prices triggered by the increase in Chinese exports, and from the rise in China’s demand for raw materials. Some economies, moreover, like those in Southeast Asia, have profited from the boom by tapping into the Asian giant’s production value chains. Others, like Brazil, have gained from the trade tensions between the United States and China and the measures taken by the authorities in Beijing to diversify imports.

To date, China’s commercial success over the last few decades has not been predicated on seeking trade agreements4. Rather, to a large extent, it has been the result of its industrial and diplomatic policy. And yet in 2022 the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) came into effect. It is the world’s largest trade deal and China is spearheading it in the hope it will be a major driver of regional trade from hereon in5. Ironically, the initiative arose to counter the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the US-driven agreement to isolate China that collapsed during the Trump administration.

China can be expected to retain its trading edge for the foreseeable future. But that dominance could be eroded by the slowdown of its economy, rising labour costs, population decline, the growing weight of domestic consumption in GDP (which will mean a rise in imports over exports) and the policies adopted by Western economies to counter their reliance on the Asian country. In these circumstances, and thanks in part to the infrastructure improvements linked to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Global South’s position as a trading partner of China will only be cemented.

China, the main investor in the Global South

China has ranked as the world’s second largest investor since 2015. It launched the “Going Out” strategy in 1999 and targeted Global South regions especially. But it was not until 2014 that China added a more strategic dimension to its role as an investor abroad with the launch of the BRI, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Silk Road Fund.

The BRI’s chief purpose was to create multiple trade routes – overland through Central Asia and by sea across Southeast Asia – to provide supply alternatives to transit through the straits controlled by the United States and its allies. The initiative also sought to offer an outlet to the country’s surplus production capacity, particularly in the manufacturing sector and construction, as the economy slowed and the property market cooled, as well as promote the development of its interior provinces. To boot, the BRI also served as a new “discursive framework” to cover and provide coherence to the multiple investments already flowing into the Global South. Abroad, the BRI helped to close the infrastructure gap in developing countries and would become a key element of China’s influence and leadership, serving to consolidate economic interdependence.

In order to achieve these goals, China modified its policy of accumulating foreign reserves after amassing nearly $4tn, three times the reserves of Japan – the world’s second largest reserve holder – and an amount equivalent to the GDP of Germany. Stockpiling reserves boosts an economy’s capacity to tackle crises. But it also has the adverse effect, from China’s point of view, of bankrolling the US government and economy. This is because currency reserves are deposited in the central bank (People’s Bank of China – PBOC) and invested in US Treasury bonds and other largely dollar-denominated assets. Foreign investment, then, allowed China to find an outlet for its reserve surplus, bypass funding the United States and place assets out of reach of possible sanctions. The chief recipients of the Chinese investment would be countries located in the Global South, particularly those with rich resources and located at key geographical points on global trade routes6.

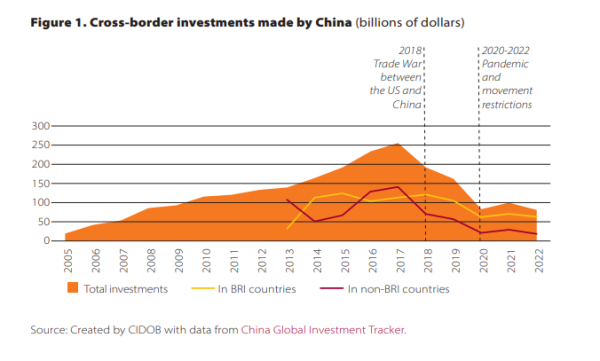

Before the launch of this initiative, the countries that now form part of the BRI were the recipients of 23% of Chinese investment. Data from the American Enterprise Institute7 (AEI) show that since 2014, on average they have been the recipients of over 60% of the investment flows and since 2020 they have received three out of every four dollars the Asian country invests. That reflects these countries’ growing importance for China and the Asian giant’s waning appetite for investment in Western countries, and the obstacles in place, because of the strategic competition with the United States and greater scrutiny of its investments.

By sector, energy (38%), transport (24%) and metals (9%) have captured 70% of the investment flows into countries that today form part of the BRI since 2005, while 60% of projects have been connected to infrastructure construction. By country, the chief Global South recipients to date are Brazil (which is not part of the BRI), Pakistan, Indonesia and Saudi Arabia. By region, Latin America has gained importance at the expense of Sub-Saharan Africa in the quest for commodities. China, meanwhile, is now one of the top five investors in cumulative terms in 16 countries8, which enhances its geoeconomic influence over them.

Yet success in terms of investment volume and access to natural resources has been overshadowed by repayment difficulties in up to 60% of the loans extended from China. This is partly due to the issue of relatively vague guidance on the part of China’s central administration and massive, fragmented and ill-coordinated implementation involving a huge number of actors9 and different economic agencies (Hameiri and Jones, 2018). Also, they are usually high-risk financial operations.

This increase in bad loans gave rise to a slight slowdown in Chinese investment in BRI countries in 2019 (Figure 1) and prompted reflection on how projects were being executed. In addition, Chinese investments had sparked local resentment over labour and environmental transgressions, fears of natural resource hoarding and a lack of quality and over-presence of Chinese companies and labour on some projects, which limited the benefit of the investments10.

Following an investment slump between 2020 and 2022 owing to the pandemic, restrictions on movement and the economic downturn in China, Xi Jinping announced during the Third Belt and Road Summit a new stage of investments with smaller projects focused on the ecological and digital transition, and more control of corruption and the quality of projects. In addition to responding to some of the failures and criticisms against the BRI, this redirection of investments towards closer to home could help dodging Western tariffs and sanctions.

China’s new role as a lender of last resort

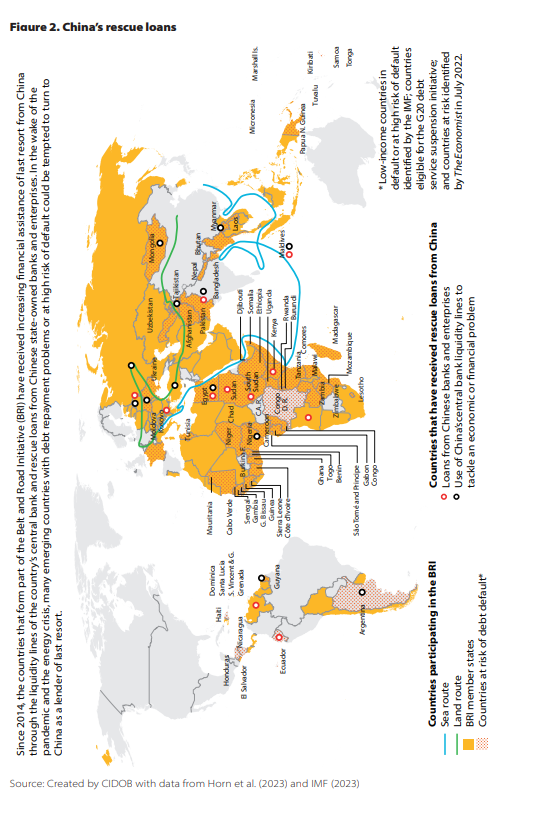

In the face of the deteriorating repayment capacity of many countries, China has decided to act as a lender of last resort (see Figure 2). Its central bank (PBOC) and rescue loans from state-owned banks and enterprises provide financially distressed economies with liquidity and protect Chinese companies and lenders from being hit by defaults.

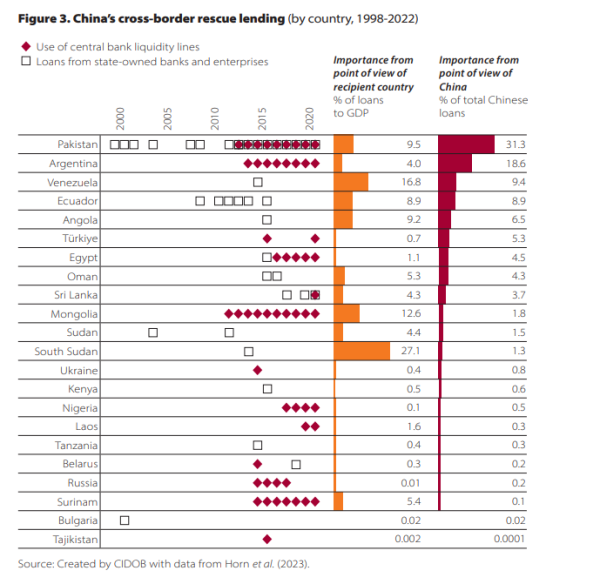

From the standpoint of the recipient countries (Figure 3), South Sudan, Venezuela, Mongolia, Pakistan, Angola and Ecuador have benefited most (with assistance in excess of 9% of their GDP). Pakistan and Argentina, however, are the countries to which China has allocated most resources.

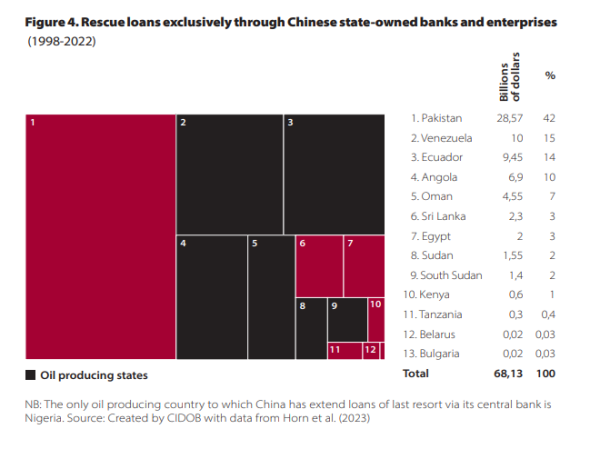

Apart from the PBOC’s emergency liquidity lines, most of the rescue operations carried out by China have been administered bilaterally through the China Development Bank (CDB) and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE). The rescue loans through Chinese banks and enterprises – not through the PBOC – have been extended almost entirely to Pakistan and oil producing countries (Figure 4). Although for several years now loans to countries with serious repayment difficulties, like Venezuela or Angola, have been severely curtailed and are only issued to countries with a clear geostrategic value, like Pakistan. In general, in debt terms, the nations most exposed to China are low-income, raw materials exporting, heavily indebted developing countries, like Angola, Ecuador, Niger or Venezuela (Horn et al. 2019).

China, then, has emerged as a major development financier and a real alternative to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Western economic order in times of crisis11. China’s loans have high interest rates, but they entail no interference in the recipient countries’ domestic affairs, nor do they come with demands for economic policy adjustments like those that triggered broad resentment from developing countries towards the United States in the 1980s, or towards the EU on the part of Greece in 2012. The only political conditionality China stipulates is respect for the “one China principle”. In addition, it must be said that China’s role as a lender of last resort challenges accusations that it is seeking to ensnare these countries in a debt trap. It could opt for seizing the collateral (e.g. infrastructures) in the event of default, instead of granting new loans and accepting the risk of non-payment.

Lastly, it should be noted that China has adapted contracts and sovereign debt to maximise the odds of recouping the investment in countries where capital inflows have traditionally been low owing to scant legal security and high probability of default. Accordingly, the main clause Chinese creditors have introduced is exclusion from the Paris Club and other collective restructuring initiatives (Horn et al. 2021). This saves them from having to write off the debts and playing a subordinate role to Western countries or multilateral institutions. While that has allowed the growth of Chinese financial flows into developing countries, now it is stymying debt restructuring efforts in a context in which there are also more private creditors with which to negotiate. In this regard, China’s participation in G20 debt relief initiatives for low-income countries during the pandemic shows its willingness to collaborate in the multilateral sphere.

In the short term, China’s new role as a lender of last resort and its participation in the debt restructuring processes of countries in distress will become increasingly important to how it is perceived and to its geoeconomic influence over a Global South12 that will continue to arbitrate between the Asian giant and other powers in pursuit of its own economic agency. Whether China maintains its investment flows into these countries in absolute terms will also be key. Their volume determines the interest created and restricts the influence of other initiatives, like the EU Global Gateway. A sudden stop in Chinese capital inflows, meanwhile, could cause financial problems in some of these economies. China therefore has a crucial financial role to play in the fortunes of the Global South.

References

American Enterprise Institute. China Global Investment Tracker [Database] https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/

IMF (2023) List of LIC DSAs for PRGT-Eligible Countries as of February 28, 2023 [Database] https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/49da23a2-bcc9-5593-bc96-470cae6b3665/content

Gelpern, Anna. et al. “How China Lends. A Rare Look into 100 Debt Contracts with Foreign Governments”. Economic Policy, 2022.

Hameiri, Shahar and Lee Jones “China challenges global governance? Chinese international development finance and the AIIB” International Affairs, Vol. 94, nº3 (May 2018), p. 573–593.

Horn, Sebastian Andreas; Reinhart, Carmen M. and Christoph Trebesch. “China’s overseas lending”, Journal of International Economics, vol. 133 (2021), p.1-32.

Horn, Sebastian Andreas; Parks, Bradley Christopher; Reinhart, Carmen M. and Christoph Trebesch. “China as an International Lender of Last Resort”. World Bank Policy Research working paper, 10380 (2023).

Molnar, Margit; Yan, Tin and Yusha Li, «China’s outward direct investment and its impact on the domestic economy“. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1685 (2021).

The Economist “The 53 fragile emerging economies” The Economist. (July 20, 2022). https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2022/07/20/the-53-fragile-emerging-economies

Notes:

1- Estimate based on data from the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) software from the World Bank and correcting Hong Kong’s distorting effect on trade statistics. The last reference year is 2019 in order to disregard the upturn in demand for industrial goods during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2- See Appendix, Tables 1 and 2.

3- See Appendix, Tables 3 and 4.

4- China has only signed 16 trade agreements (ASEAN, Asia Pacific Trade Agreement – APTA, with Australia, Chile, Costa Rica, Georgia, Hong Kong, South Korea, Macao, Mauritius, New Zealand, Singapore, Iceland, Pakistan, Peru and Switzerland), representing 15 countries and 30% of global GDP.

5- This free trade agreement among 15 countries of East Asia and the Pacific covers a third of the world’s economy. The UN’s trade division calculates that it will remove 90% of tariffs and increase interregional exports by $42bn.

6- Appendix, Table 5.

7- The China Global Investment Tracker is the main source of open data on China’s foreign investments. These investments are characterised by their opacity and difficulty in tracking. According to Gelpern et al. (2021), Chinese contracts contain unusual confidentiality clauses that forbid the borrowers to reveal the terms or even the existence of the debt, while Horn et al. (2019) estimate that 50% of the loans to developing countries are not gathered in IMF or World Bank statistics. AEI data make no distinction between development aid and the rest of the investments because in China’s case both are frequently used to fund the same type of infrastructure projects.

8- China is the main foreign investor in Tajikistan, Cambodia, Kyrgyzstan and Sri Lanka; and the second largest in Niger, Myanmar, Mongolia, Zambia, Nepal and Bangladesh.

9- Prominent agencies responsible for BRI implementation are ministries (primarily the Foreign Ministry – MFA, the Ministry of Commerce – MOFCOM, the latter being the more dominant, and the Ministry of Finance, which holds the purse strings); the National Development and Reform Commission, which spearheaded the design of the BRI and grants budget; commercial and institutional banks, including the Export-Import Bank (Exim Bank) and the China Development Bank (which grant loans close to commercial interest rates); and provincial governments and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). On top of all this is the role played by private companies, which in some cases have accounted for nearly half of Chinese investment abroad.

10- Much of the infrastructure financed by China’s loans is built by Chinese firms, which sometimes means the cash may never leave the country.

11- Between 2016 and 2021, China loaned $185bn to 22 countries, equivalent to 34% of what the IMF loaned globally in the same period. China is the world’s largest bilateral creditor (Horn et al. 2019).

12- China is the main bilateral creditor of over half the 73 low-income countries eligible for the G20 debt service suspension initiative. China holds over 20% of the total debt of 22 of those countries, although just six countries (Angola, Ethiopia, Kenya, Laos, Pakistan and Zambia) account for more than half of the Chinese loans.