V4 Migration Policy: Conflicting Narratives and Interpretative Frameworks

During the migration crisis of 2015-2016, the Visegrad (V4) countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) articulated a very pronounced and distinctive stance on the highly debated issue. The V4’s approach basically stood against the open-door policy attributed to Germany and Sweden (and the European Union in general) and thus the central European countries and their suggestions raised interest (and eyebrows) all over Europe and the world.

Consequently, many different narratives have been formed regarding V4 migration policy. The different political, economic and social actors of the European public interpreted the four countries’ stance from various perspectives, framing it in different contexts: some saw it as a consequence of the “illiberal” tendencies in the region while others considered the Visegrad approach as proof of the European east-west divide.

When one tries to systematically analyse the different narratives about V4 migration policy, it becomes evident that almost all of them can be put into three categories, which (intentionally or unintentionally) also resonate with the main schools of International Relations (IR) and foreign policy analysis (FPA). The first considers migration policy as a consequence of state interests and geopolitical circumstances using neorealist reasoning. The second group of narratives uses domestic party politics as the best explanatory factor of the V4’s foreign policy on migration issues, echoing the neoliberal institutionalist approach. The third category, which uses the basic principles of social constructivist methodology, explains the central European bloc’s approach to migration based on particular identities and norms in the Visegrad countries.

In the following pages, the authors seek to describe the three types of narrative on V4 migration policy; while, at the end, we compare them on the basis of their explanatory value. The strict separation and comparison of these interpretative frameworks serves two broad aims. First, avoiding the mixed usage of IR traditions prevents us from mixing separate methodologies. Second, it also helps us to differentiate between the causes of the Visegrad behaviour, whether it is a structural necessity or, for example, part of a domestic political strategy. Our analysis aims at answering why this policy emerged among the Visegrad countries and not in other regions of the EU.

The migration policy of the Visegrad countries

The bloc consisting of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia first articulated its common position on migration in September 2015 and several times afterwards (Visegrad Group,2015a). On the basis of these statements, we can summarise V4 migration policy in three points:

a. Protecting the external borders of the EU and underlining the importance of fulfilling the obligations deriving from the EU acquis

Preserving the integrity of the external borders of the European Union has served as a cornerstone for Visegrad migration policy. The reasoning behind putting the emphasis on this question is built on the interpretation of the obligations originating from the European legal norms, especially the Schengen Agreement and the Dublin Regulation. Facilitating the free movement of people within the territories of participating countries (mostly EU member states), the Schengen Agreement requires further regulation among and attention from its signatories to preserve the integrity of the system and the security of its members, since they apply common rules on people crossing European borders coming from third countries. The Dublin Regulation – another important tool within the Schengen framework from this perspective – deals with the question of asylum seekers.

The migration crisis of 2015 challenged these rules and made their consistent fulfilment quite difficult, especially due to the different approaches implemented by member states. In accordance with the Schengen system, internal borders were reintroduced temporarily by Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden and Norway. According to the V4’s approach, in order to avoid the collapse of the system, further steps were necessary to protect the external borders of the Schengen area. This is why Hungary closed its border with Serbia and Croatia, as Slovenia also did with Croatia. Another cornerstone of the V4’s migration policy is standing against internal border closing and against the idea of a mini-Schengen, which was proposed by the Dutch presidency in order to develop a smaller open border area made up of the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany and Austria, which would work together and control its external borders more carefully (Euractiv, 2016).

On the other hand, Visegrad countries also advocate the reform of the Dublin Regulation. But until the member states reach an agreement on that, they have to fulfil the existing rules which require the protection of external borders (Visegrad Group, 2016a). On the other hand, according to the V4’s policies, the effective functioning of the Dublin system is indispensable and the allocation mechanism and penalty system for refusing to comply with it, which means that the Commission proposes a sanction of €250,000 per refugee, is unacceptable (Visegrad Group, 2016b).

b. Effective management of the root causes of migration flows, which could help reduce the number of migrants

In order to lift the pressure created by the migration crisis, the Visegrad countries propose to seek solutions outside the EU, an idea that basically consists of two parts. First, one has to identify and deal with the root causes of migration. “Continuing the support to the international coalition fighting Da’esh in Iraq and Syria and providing various means of contribution (political, military and humanitarian) to the efforts of the coalition and to the stabilization of Iraq as tangible forms of tackling the root causes of the migration flows” (Visegrad Group, 2015a). Second, the Visegrad countries propose to increase financial, technical and expert support for the origin and transit countries (Visegrad Group, 2015b) of migration. Another recurrent element of the V4’s rhetoric is to reiterate the concept of “hotspots” (Visegrad Group, 2015b; 2016a) inside and outside the EU, besides underlining the importance of developing both FRONTEX and EURODAC. It was in this framework that the V4 welcomed the EU-Turkey deal too.

c. Refusing Germany’s open-door migration policy

On the basis of the above-described points, there is a decisive difference between the migration policies of Germany and that of the V4 countries, who fully disagree with the so-called “open-door policy” (DW, 2016). The political conflict surfaced most clearly regarding the different proposals for a quota-based refugee relocation system. First, in September 2015, the member states agreed to relocate 120,000 refugees from Greece and Italy, a decision which was refused by the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania. Poland, despite its previous rhetoric, voted in favour of the proposition. Nonetheless, after the change of government in Warsaw, the V4 stood united against a new proposal submitted by the European Commission in May 2016 aiming to relocate 400,000 people in need of international protection. Beside these three points, the V4 also agree on and advocate the importance of consensus-based decision-making among the member states on European integration (Visegrad Group, 2016c). This consensus is important for the central European states in connection with the implementation of the EU-Turkey deal, the protection of the external borders of the EU with proper border management, the establishment of fully functioning hotspots, the implementation of an effective return policy and the treatment of the roots of migration.

Conflicting narratives of the V4 migration policy

Due to the highly politicised nature of the debates regarding migration policy, it is useful to interpret Visegrad migration policy through the different schools of thought of International Relations theory. Using consistent methodological frameworks, one can set up three separate narratives on the subject, namely, explanations focusing on: state interests and geopolitics (neorealism), domestic politics and party competition (neoliberalism), and social values (constructivism). This way we can avoid superficial analyses and labelling.

Geopolitics and intra-European competition: the neorealist narrative

It is not self-explanatory to view migration through the lenses of geopolitics and geopolitical struggles. Many considered the cross-border movement of people a consequence of globalisation – the victory of the new world order over the traditional territorial state system. Nonetheless, after a closer examination, one can clearly see that geopolitical considerations did not cease to shape state responses to migration. “Across the world”, argues Roderick Parkes, “countries are not only trying to reassert control of their borders but to use people flows and differences of population size for geostrategic gain” (Parkes, 2015: 1).

Interpreting migration policies based on these premises (and neglecting domestic aspects) is also in accordance with the most mainstream traditions of IR theory and, specifically, neorealism. Migration has not been on the top of the agenda for this school of thought, since it was considered to be a part of “low politics”. Nevertheless, after 1990 – due to theoretical advancements and the growing volume of the cross-border movement of people – the question became securitised in the West, especially after 2001 (Hyndman, 2012: 246-247) and was considered to be related to state security and sovereignty (Zogata-Kusz, 2012).

However, the level and process of securitisation differed in the various European states to a great extent. Parkes presents a very thorough analysis of how geopolitics shape national considerations regarding migration policy through two factors. Firstly, the different types of borders inside the EU shape national regulatory traditions regarding border control policy. In this regard, we can distinguish between three categories:

• states with no external borders, which experience non-EU migration

through major air and seaports (Germany, Great Britain, France);

• states with massive external sea borders (Italy, Spain); and

• states with massive external land borders (Hungary, Poland).

These geopolitical circumstances affect the way in which governments perceive the phenomenon of mass migration. Members of the last two categories are more likely to consider the mass influx of people a security threat since they are ones that experience the crossing of external European borders. From their perspective, mass migration primarily means an external process which challenges the control over the state’s territory and they react by emphasising the physical safety of borders. “Poland is responsible for protecting the second longest section of the EU’s external land border”, which is why “any kind of mechanism to strengthen solidarity in the protection of the external land border (including burden sharing) is evidently in Poland’s interest. In this respect, Hungary’s interests are quite similar” (Gaciars, 2012: 30). On the other hand, countries without external Schengen borders are those which have the biggest air and seaports and have their own set of problems, which is why migration is securitised more in connection with terrorism and not the movement of people by itself.

Secondly, geopolitics also play its part through economic forms. As Hyndman put it, “the demand for skilled labour in most countries of the global North has created a competitive global market place for potential migrants with expertise and professional background (…). So migrants are welcomed in, or at least their labour is” (2012: 245). That is why there is a strong urge for such states, especially Germany, to distinguish between labour migration and irregular migration as securitisation only affects the second category, not the first (Parkes, 2015, 10).4 This differentiation is non-existent in the Visegrad countries, which do not serve as a destination for labour migration, which is why securitisation has reached a higher level.

These circumstances play a huge role in shaping security perceptions, nonetheless they are not enough in themselves to describe the Visegrad stance on migration, since Slovakia and the Czech Republic do not share the same attributes as Poland or Hungary. That is why we have to introduce another aspect as well.

Migration has always been a cause and a tool in the competition between the different geopolitical blocs inside the European Union. This rivalry traditionally occurred between the north and the south of the continent (based on the above-described differences in perception), nonetheless the enlargement in 2004 paved the way for central Europe to join the game.

Members of the Visegrad group – a bloc which has always been based on interests and pragmatism – had several incentives in the last years to pursue their interests on the European level collectively. Firstly, the economic crisis (and the debates regarding the future of integration and Brexit) have left the European Union highly divided (Schweiger, 2013), which can be seen as an opportunity for the V4 to enhance their leverage. Secondly, due to the new voting system introduced by the Lisbon Treaty, the institutional power of the Visegrad countries diminished as they remained unable to form a blocking minority. “The four are increasingly aware of the prospect of their being marginalised in the emergent EU setup” (Gostynska & Parkes, 2012: 5), which urged them to tighten their grip on the pursuit of common interests.

From this perspective, migration was basically a tool to increase the leverage of the Visegrad countries which caused political tensions. According to the neorealist argument, the distribution of power determines international relations, thus conflict is caused by changes in the balance between states. The V4 lacks the material resources to question the leadership of Germany, France or the United Kingdom, but in the framework of the migration crisis, their bargaining power is much higher than usual. Due to the routes of the movement of people, the four central European countries are among the strongest stakeholders in the management of the crisis. To put it shortly, their geopolitical allocation became a capability and changed the European balance of power in this policy area, which automatically creates conflict from the neorealist perspective.

All in all, geopolitics has a high explanatory value when it comes to the interpretation of Visegrad migration policy. First of all, disposing over huge external land borders on the edge of the Schengen zone, the four central European countries – primarily Poland and Hungary – consider migration solely as a security threat primarily in connection with border security. In contrast, the states in the core region of Europe have more differentiated views of migration: as destination countries they consider the movement of labour force an advantageous phenomenon. That is why the level of securitisation is much lower. Second, the crisis of 2015 became a field of the internal struggle of the different European geopolitical blocs. In this regard, the novelty in the current situation is not that migration became a matter of political rivalry but rather the fact that central Europe became a player besides the traditional “north” and “south”. From this narrative perspective, migration was only a tool and not the aim of the political debates inside Europe.

Domestic and party politics: the neoliberal narrative

Following the neoliberal school of thought, the actions of states cannot only be interpreted by states’ capabilities and power, as neorealists argue. Foreign policy can also be understood as a given set of state preferences in the form of “national interests” that grow out of domestic political movements. Neoliberals argue that, on the one hand, states represent a subset of domestic society whose interests are taken into account by state officials, who, on the other hand, define state preferences and act according to these preferences in world politics. Therefore, domestic politics do matter when formulating foreign policy choices, since political institutions shape those choices (de Mesquita & Smith, 2012).

When analysing the current migration crisis and the different interpretations of V4 policy choices, the neoliberal narrative invites us to take a closer look at the literature of party competition and the role of niche parties in the domestic political system of a state in order to understand the possible reasons behind the reactions of the Visegrad countries’ governments.

According to the party competition theory of Abou-Chadi (2014) regarding niche party effects on mainstream parties, there is a connection between the emergence of niche parties and the politicisation of immigration by mainstream parties. Green parties, ethnic regionalists and radical rights parties are also commonly referred to as niche parties. However, there are three generally accepted attributes that characterise such political groups: (1) they usually raise issues that are not part of the traditional class cleavage; (2) they address only a very limited number of issues and sometimes even look like that they are single-issue parties; (3) the issues advocated by niche parties intersect with traditional lines of cleavage and cause a shift in partisan alignment (Wagner, 2011).

Party competition theories suggest that parties do not only have different policy positions, they also prioritise different issues in order to become the owner of a particular issue (issue ownership). A party owns an issue if voters consider the given party the most competent and effective problem-solving actor on the issue. Usually, immigration is not necessarily

and exclusively connected by voters to only one party. (Abou-Chadi, 2014) However, before the refugee crisis, immigration was usually addressed by radical right parties who could thrive in the political environment of the European Union by advocating issues like immigration, national sovereignty, international terrorism and globalisation after the financial crisis (Kallis, 2015).

In the wake of the current crisis, immigration became a top priority issue. As radical right parties increased their support among voters, party competition increased as well. This means that if radical right parties gain support from the voters, pressure starts to mount on conservative and moderate right-wing parties forcing them to move their position stance on immigration to the right in order to avert further success of the radical right parties. In such a way, mainstream parties tend to politicise immigration, elevate it into their own political agenda and adopt more restrictive immigration policies to counter the possible electoral loss they might suffer.This strategy is called the accommodative or adversarial strategy, which is based on the spatial logic of party competition and is used to trigger partisan realignment (Abou-Chadi, 2014).

By examining the results of the latest outcome of the elections in the V4 countries and comparing them to the previous elections in the given countries, it is striking that radical right-wing parties became stronger by acquiring higher percentages of support in the general elections. In the Czech Republic the radical right-wing party Dawn - National Coalition (Úsvit Národní Koalice), which came into existence in 2013, gained 6.9% of the votes in the 2013 elections (electionresources.org, 2014). Jobbik, the Movement for a Better Hungary managed to increase their electoral support from 16.67% to 23% from the elections of 2010 to the 2014 elections in Hungary (OSCE, 2014). Similarly, in Slovakia, People’s Party - Our Slovakia gained 8.4% of the votes in 2016, compared to 1.58% in 2012 (OSCE, 2016a). In Poland, a delicate situation emerged as the strongest voice of anti-immigration policies, the Law and Justice Party, won the elections in 2015 and overtook the previous ruling party, the Civic Platform. Although PiS is a mainstream party, niche parties like Kukiz 15 address issues other than immigration. For example, ownership of the media and nationalism, which has also been addressed by PiS since Kukiz 15 gained 8.81% at the last elections (OSCE 2016b). These tendencies suggest that niche parties have indeed increased party competition and have set the focus on issue ownership. Contrary to the neorealist narrative, the neoliberal school interprets V4 migration policy in the framework of domestic political competition, not of geopolitical struggles. Governing parties in central Europe tried to prevent radical right-wing parties from owning the issue of migration and therefore built up their own strategy against the mass movement of people.

Social norms and xenophobia: the constructivist narrative

In order to interpret V4 migration policy, constructivism is a useful tool to trace back the causes of the difference between V4 migration policy and that of the rest of the West. One possible interpretation emerged which explains policy variation with social norms that are generally present in post-communist central Europe. According to this narrative, the lack of historical experience with migration and the socialist past made the societies of the Visegrad region more hostile to foreigners, which is also reflected at foreign policy level.

However, data does not support the conception of central Europe as a xenophobic bloc. Quantitatively, norms related to migration and foreigners are constantly changing in European societies, and there are huge differences in this regard inside the V4 too. According to Nyíri, “surveys refute the simplistic but popular notion that Eastern Europe is a homogeneously xenophobic region (….). Indeed, differences in levels of xenophobia between individual Eastern European countries are as great as between individual Eastern and Western European countries” (2003: 30). This notion was supported by other analyses as well (Card et al, 2005). Moreover, this research also points out that social values related to xenophobia and intolerance have changed rapidly in these societies since 1990 (probably due to the communist past), which would suggest that they are not quite fixed.

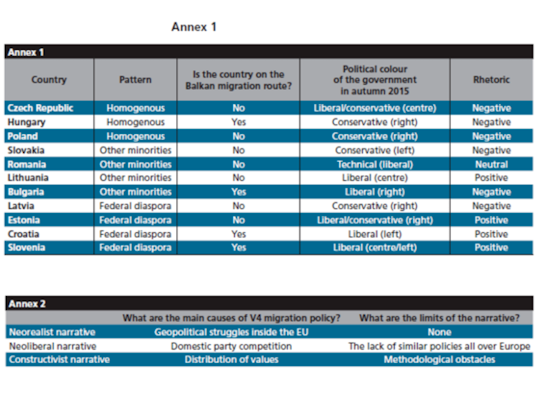

Consequently, the social constructivist narrative should not be based on generalised xenophobia in the Visegrad countries, but more on the easily changeable nature of such values in the region, which can urge politicians to implement more “national” policies. Rovny investigated the distribution of norms about migration in the post-communist region and found that migration policy in the central and eastern European region depends on states’ historical experiences with participation in communist, federalist structures (federal heritage) and co-existence with other national minorities (ethnic affiliations). According to this narrative (see Annex 1), there are three patterns that influence migration policy outcomes: 1) countries with a transition to democracy by seceding from a communist federation which contain a federal diaspora; 2) countries in which a prominent ethnic minority is present other than the ethnicity of the federal centre; 3) countries with ethnic homogeneity. The Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland belong to the third group. The theory suggests that in these ethnically homogeneous countries party competition is not influenced by ethnic minority topics.5 The second pattern describes Slovakia, where the left-wing has a tendency to oppose migration. The established patterns alone do not clarify why some countries are more restrictive than others (Rovny, 2014).

Two other important factors affect policy outcomes: the current governments’ political ideology, and the geography of the country, which determines whether a migration route crosses it or not. From this point of view, a government of left or right-wing conservatives tend to produce negative rhetoric towards migration in the current migration crisis regardless of whether their country is on the Balkan migration route or not. However, in the case of Bulgaria – which is on the Balkan migration route – the liberal government also has a negative stance (Rovny, 2016).6 By examining the dataset provided by Rovny, we can conclude that there is negative rhetoric regardless of the government’s colour and whether the migration route crosses the country or not. Secondly, where other minorities are present than the ex-Soviet federal ethnicity, it seems like that the variables of conservativism or being on the route may both 5. Rovy does not specify the connection between Roma minorities and party competition in these countries even though this is an important political topic, especially in Hungary and Slovakia. 6. The political colour of the Bulgarian government which is composed of GERB, the Reformist Bloc and the Alternative for Bulgarian Revival in a form of partnership agreement is labelled a liberal government by Rovny who uses the Chapel Hill Expert Survey to determine the policy and ideological stances of national political parties. influence governments to be negative because of the example of Bulgaria. In countries where a federal diaspora exists, conservativism seems to cause negative positions.

Rovny’s model is somewhat more adequate for interpreting the present processes and invites us to assume that conservativism coupled with ethnic homogeneity might be behind a more restrictive governmental policy towards migration in Visegrad countries.

Comparing the narratives

After setting up the three narratives, one is able to compare them on the basis of their explanatory value. As was stated in the first pages, our goal is to determine the reasons why the V4 developed this migration policy and why other states in the EU did not do so. While neorealists attribute the phenomenon to geopolitical exposure and intra-EU struggles, neoliberals focus on domestic party competition, and constructivists on norm distribution.

Although each narrative provides useful insights on the question, the authors believe that it is the neorealist framework which has the most explanatory value. One can explain the Visegrad migration policy without making any reference to domestic politics and social values without any questions left unanswered. Introducing domestic politics, the neoliberal narrative seems adequate. Nonetheless, it is not able to explain why central European countries were the ones to make the anti-migration alliance.

The migration crisis created an international environment in which all parties, especially governmental parties in CEE region, should have reacted to the issue regardless of niche party positions, since the Western Balkan route proved to be a popular migration line to the EU. It is also clear that niche parties started to gain more popularity in other countries inside the EU. Despite the increase of party competition, government reactions did not always shift to anti-immigration sentiments. Alternative für Deutschland in Germany also gained a lot of support from voters during the last regional elections in 2016, but despite the fact that the German open-door policy changed since the beginning of the crisis, the government’s rhetoric did not shift to a negative spectrum as it did in case of the V4 countries (The Guardian, 2016).

Lastly, the constructivist narrative has the severe limitation that without proper research, one can hardly establish a causal relationship between social norms and policy outcomes. Methodologically, we can only analyse the conjunction of these parameters but we cannot prove that they served as a cause of V4 migration policy. The true value of the constructivist narrative is to shed light on the social environment of this policy – central European societies did not necessarily support their government’s approach a priori, but without strong, deep-rooted values in connection with migration they accepted the political narrative.

Therefore, from a strictly theoretical perspective, the geopolitical investigation serves as the best explanatory framework to interpret the Visegrad countries’ migration policy.