Tunisia is Economically Adrift

As Tunisians head for parliamentary and presidential elections next autumn they face a stark reality. Most of them are poorer today than they were before the Jasmin Revolution toppled the Ben Ali regime in January 2011, setting off a wave of protests across the Arab world. The country’s assets remain essentially in the same hands although the Islamist party Nahda has been handed a slice of the cake. The media are nominally free but TV stations belong to powerful businessmen and manipulate more than they inform. Corruption has been well and truly democratised.

Young educated talent continues to flee the country, essentially to France, Germany and Italy. Most people have turned away from politics, disgusted by a spectacle which combines low comedy, corruption and an increasing misuse of statistics by the government, as the respected economist Hachemi Alaya alleges in his article La Tunisie prise au piège d’une addiction aiguë a la chiffrite published at the end of May in Ecoweek.

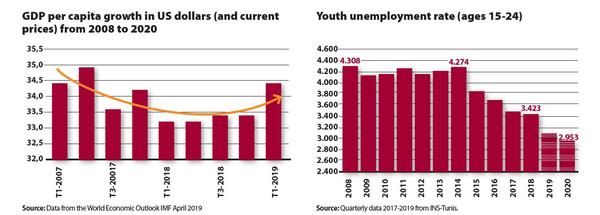

Democracy seldom flourishes when stomachs are empty. One of the most telling statistics today is that 20% of the population is poor. That is the inevitable consequence of the country’s wealth tumbling from $44.8bn in 2008 to just below $40bn last year and a forecast $35.2bn in 2020. GDP per head has declined by a fifth since 2011, stands at just over $4000 today and is forecast by the IMF to fall below $3000. Tunisia has stopped investing and happily spends money which it does not earn on consumption. Investment as a percentage of GDP peaked at over 30% in the 1980s, stood at a respectable 25.6 % on the eve of the fall of Ben Ali but slipped to 20% last year. Savings have more than halved to 8.9% from what they were a decade earlier. The fast growth in foreign indebtedness is all but the natural consequence of the prime minister since 2016, Youssef Chahed’s lack of stomach for reform, let alone economic strategy.

However, true direct foreign investment increased by 9.8% during the first three months of 2019 compared with the same period in 2018 which itself had witnessed a 25.2% increase with France, followed by Qatar being the key source of such flows. FDI flows are unlikely to boost GDP growth this year which the April IMF forecast put at 2.7%, revised downwards from the 2.9% of last October.

Unemployment remains a festering wound which weakens the economy and the body politic. The economic, social and educational divide between a relatively well-off coast and a poorer hinterland remains. Tunisia is, in economic, social, educational and health terms, two distinct countries. Young people who bear the brunt of unemployment refuse to vote as they find it impossible to believe in a democracy that by contrast many Western think tanks and politicians continue to offer as an example to the Arab world.

Many Tunisians know their politicians are corrupt, their media increasingly in thrall to private business interests and many debates in the national assembly pointless. The Tunisian authorities stopped 6,369 Tunisians from leaving in 2018, almost twice as many as in 2017, according the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights. About 1600 hundred died at sea in 2018, only a fraction fewer than the year before. They are disillusioned about the future of what they nickname Jumhurriyat al-shaykhayn, the Republic of the two Elders, or the gerontocracy of President Beji Caid Essebsi and the Islamist leader Rached Ghannouchi. Many Tunisians dismiss their democracy as “fake”.

The Tunisian economy is kept afloat on a constant infusion of international aid. It will need Tunisian Dinars 10bn this year according to government estimates. The cost of borrowing increased in 2018 compared with 2017 and is expected to continue to do so this year but the IMF judges the country’s level of indebtedness as manageable, not least because much of the debt contracted with the IMF, the European Union, the World Bank and the African Development Bank enjoys low interest rates and long maturities. The IMF’s satisfaction at seeing the state budget deficit consolidated – it is down from 6.1% of GDP in 2017 to 4.8% last year -cannot hide the huge increase in the cost of the public employee wage bill (112% between 2010 and 2017) and public debt (from 39% of GDP in 2010 to 71.7% in 2018). The inevitable result of this increase is that the burden of state debt repayments rises every year. It accounted for just over one fifth of government expenditure last year.

As a consequence public investment dropped from 7.2% of GDP in 2011 to 5.4% last year. State income from taxation, notably from increases in value added taxes on petrol have raised the cost of transport which together with much higher food prices affects poorer or middle income Tunisians disproportionately. Overall economic activity has slumped. Younger entrepreneurs find it very difficult to raise loans if they cannot offer property as collateral: 46% of micro enterprises borrow informally and those who have a bank account keep transactions to a minimum according to Hachemi Alaya in Ecoweek on 3 Juin 2019. Tunisian banks are happy to deal with well-established clients but show little interest in the small fry. We can compare these figures with Kenya where the percentage of people holding bank accounts increase from 32% in 2011 to 72% in 2015. The World Bank meanwhile runs seminars on the digitalisation of payments which is rather beside the point. There is no political will to increase taxes on the professional classes such as doctors and lawyers, let alone the thousands of cafes whose tax burden is much lighter than the one which weighs on salaried Tunisians. The banking sector is enjoying record returns on capital and profits. BIAT one of the country’s leading banks enjoys a return on assets of between 15-20%.

A $2.9bn IMF package which was agreed in 2016 is, meanwhile, very much on course. Although the World Bank has reached its technical limit of lending to Tunisia, it will no doubt find ways to lend more because strong western support for what it argues is the unique democracy of its kind in the Middle East. The EU has committed Euros 800m to the country since 2011. Tunisia has increased its sources of outside financing to include Saudi Arabia which recently lent $500m on favourable terms.

Yet the painful fact of the matter remains that state debt has tripled between 2011 and 2018. Recent interest rate rises are hurting investment. The aspiring democracy inherited a country whose public finances were healthy, which boasted the tidy sum of TD3.5bn from the recent (in 2011) privatisation of Tunisia Telecom, one in which state salaries accounted for a third of their present day level. The production of phosphates has collapsed from 7.5m tons in 2010 to 3.3m tons last year while the number of “workers” in the phosphate and fertiliser sectors has been multiplied by five to 30,000. The recent decline in the price of phosphates and phosphate based fertilisers, which a recent World Bank report suggests is set to last, should encourage the government to act, but in the present state of political stasis, that is unlikely. Phosphates, fertilisers and crude oil accounted for 30% of exports in 2010 but only 9.1% in 2018.

What do Tunisians want from their government?

The question which remains unanswered is what happens if the loans and aid which support current activity and a spiralling debt are not accompanied by fundamental economic and financial reforms. More fundamentally, in the words of a respected former minister of Finance Fadhel Abdelkefi, “what do the Tunisians want and expect from their state”? If political leaders, the powerful trade union UGTT and businessmen with an inside track continue to treat the state as a milk cow, Tunisia will end up poorer. Mr Abdelkefi’s words carry weight because as minister of Foreign Investment and Finance for a year to August 2017, he attempted to enact bold reforms before attacks on his integrity regarding an old customs lawsuit, which were eventually dismissed by the courts but led him to resign. The prime minister did nothing to support his minister which convinced many that Mr Chahed was not serious in his publicly stated intention of reform. A member of the World Bank team in Tunis was more blunt stating that “the coup launched against Mr Abdelkefi was a coup d’état… the first step in the deep state regaining control… Tunisia is akin to a frog in boiling water”. The prime minister has done nothing over the past twenty two months to suggest he is seriously interested in reforming the economy.

The promises made by leading politicians, in the run up to next autumn’s polls that, come 2020, a real start will be made on serious economic reforms fall on deaf ears. Such siren calls are dismissed as tmenik, false promises, in the local vernacular. What political value will elections in which a majority of Tunisians under the age of 30 do not cast a ballot, as happened in last May’s local elections, have? Would such an election offer any chance of a bold remit for reform? If no party commands a majority will Tunisians not be treated to the unseemly horse-trading which passes for democracy? The stage will not be set for men of conviction and integrity to push for bold reforms.

Meanwhile, political offers are all the rage. The salaries of employees of the state have been increased, as have the minimum wage and pensions, which of course flies in the face of IMF orthodoxy. What the government gives the IMF with one hand it withdraws with another. It is a game of liar’s poker. Foreign investment has often taken the form of Gulf countries buying up financial assets in Tunisia though France remains the first source of foreign investment. Turmoil in Algeria and Libya has also pushed foreign currency fleeing both countries into the large informal sector which sustains activity but does not show up in official statistics. Remittances from Tunisians abroad, which earn the country more than tourist receipts, dropped by 9% during the first quarter of 2019 compared with the same period last year.

New policies in farming & transport would boost the economy

Mr Abdelkefi points to three sectors desperately in need of new ideas. When considering the future of the phosphate and fertiliser sector, why not taking into account the prospect of stock options for the workers? Unless and until the workforce and the managers can be brought together to face what the future of their country might be, there is no hope of a solution. The second idea relates to state farms, terres domaniales. These cover 500,000 hectares and occupy some of the richest land of the country. Thousands of hectares remain fallow. As more and more people invest in prime quality olive oil, the export of which is one of the recent success stories of Tunisia and good quality fruit and vegetable preserves, this land deserves to be privatised.

The Moulins Mahjoub offers a perfect example of a private domain and company which exports 100 tons of cold pressed olive oil to 25 countries worldwide. A further 100 tons are used to preserve artichokes, peppers and garlic, all of which are sold abroad. The farming sector employs 15% of all Tunisians and accounts for 10% of the value of exports but remains the Cinderella of economic development. The state’s attention is lavished on coastal tourism and industrial development plants. Private investment and privatising the terres domaniales is the answer to more employment in the countryside in the poorer north and north eastern regions. Tunisia is ideal for the production of almonds and pistachios. These are not subject to import quotas in the EU which imports 70% of the almonds it consumes.

No one is more aware of the country’s potential than Leïth Ben Becher who created the free Syndicat des Agriculteurs de Tunisie (Synagri) after 2011. He is also a member of Qadiroon, a civil society association which brings together private citizens and political parties. The question is why does the government still support an official farmers union? The answer, put to former president Ben Ali a decade ago by the chief scientific adviser of Tunisia’s largest food processing company Poulina, Adel Sahel is just “get rid of the ministry of Agriculture”. The Banque Nationale de l’Agriculture’s loan portfolio only boasts 20% of its lending to farmers who overall only receive 5% of loans to the private sector.

One of former president Bourguiba’s greatest political mistakes was to nationalise the farming sector. Up to the eve of his sacking in 1969 by the president, the all-powerful economic czar, Ahmed Ben Salah, had his methods on central planning strongly endorsed by the World Bank which was convinced that Tunisia’s economy was about to take off. Forty years later it was equally gushing in its praise for the Tunisian economic model right up to the fall of Ben Ali.

Privatising state lands in no way precludes setting aside some of them for smaller farmers whom the state could help to increase their small holdings. Farming and food processing are essential to create jobs, preserve the environment and increase exports. One need only look at the statistics of the growing contribution farming and fishing are making to GDP and exports to appreciate why developing a real farming strategy would pay dividends – all the more as growth here would help reduce disparities in regional income and help reduce land erosion.

Bold policies in air and maritime transport could also give a huge boost to the economy. The Tunisian government is waiting for the European Union to agree to its request for open skies which would allow low cost airlines to operate freely, but it has excluded the airport of Tunis Carthage, by a long stretch the busiest in the country, due to opposition from the UGTT. Tunis Air is bleeding money and offers a service which can only be described as a permanent insult to its customers. The payroll has increased since 2011, but most “new employees” do not even bother to report for work, just drawing a comfortable pay-check at the end of the month. To add insult to injury, a brand new airport was completed ten years ago at Enfida, due south of Tunis, which hardly sees a plane land. Had a fast train connection been built and Tunis Carthage closed, this would have revolutionised air transport in the north of the country.

The capital’s airport occupies 1000 hectares of prime land in the heart of Tunis. Were this land to be redeveloped in a way that restructured the heart of a capital desperately short of green spaces and where traffic congestion is permanent, the benefits in terms of urban environment would be huge. The whole sorry saga of Enfida and Tunis Air underlines that, contrary to what many of its leaders tell foreign lenders, Tunisia is not short of cash. It is short of political leaders with bold ideas and the will to push them through. Where maritime transport is concerned, a project was drawn up a decade ago to build a new deep water port on the seashore close to the airport. But experts argue than one fifth of that money could finance the modernisation of all existing ports.

A third sector which needs to be overhauled is tourism. The sobering fact is that 8.3m tourists in Tunisia earned the country Tunisian Dinars (TD) 1bn in 2018 whereas 12m tourists earned neighbouring Morocco TD12 bn. Improving Tunisia’s image, improving the quality of tourists who visit the country is urgent. But sun and sea on the cheap remains the mainstay of the tourist sector. The growing number of maisons d’hôtes suggests that individual Tunisians are ahead of the game. They are aware of the lure of Tunisia’s rich legacy of Roman and Carthaginian archaeological sites, mosques and old fortresses, desert oasis, of the attraction of gastronomical tours taking in olive oil and local produce. Building a new image of the country which would blend in the high tech sector, notably IT and health tourism, both of which enjoy the advantage of a good average standard of education is essential.

At the very least, could the government get the 150 or so hotels currently closed, sold, refurbished and reopened? The weight of bad debt or unrecoverable loans of certain Tunisian banks such as STB, notably in the tourist sector, is very large but undisclosed. The World Bank proposed a plan to restructure them and sell off the loans, at a discount which hotel owners, many of whom had borrowed money in what were speculative operations rather than hotel development, refused. But lack of political courage hampers all attempts to modernise the sector.

So long as Tunisian leaders remain convinced that they can get away with going cap in hand to international lenders and, in exchange for yet more false promises, get money, there is little chance of serious economic reform. True, Tunisia suffers economically from Libya’s turmoil but the argument that the country is the only Arab democracy increasingly irritates foreign lenders. The sums lent to Tunisia are, by international standards small, so lenders can forget the country most of the time. Tunisia’s foreign partners are doing the country no favours by never calling its political leaders’ bluff. Sooner or later, the economy will exact its revenge on the political class but there is one silver lining. The political class would be all the more unforgivable if it fails to get its act together because, unlike most of its neighbours, it does not have a powerful and predatory military breathing down its neck.

Key words: Tunisia, elections, economy

E-ISSN: 2013-4428

D.L.: B-8439-2012