As North African energy links are redrawn, Italy becomes Europe’s southern gas hub

We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual and these interests it is our duty to follow

Lord Palmerston, House of Commons, 1st March 1848

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is accelerating a reshaping of the political and economic landscape of the central and western Mediterranean, above all regarding the energy sector and, specifically, gas supply.

In this context, Italy is reasserting its influence, especially in the central Mediterranean as it replaces its Russian-sourced gas with greater amounts of Algeria, Egyptian and now Israeli gas.

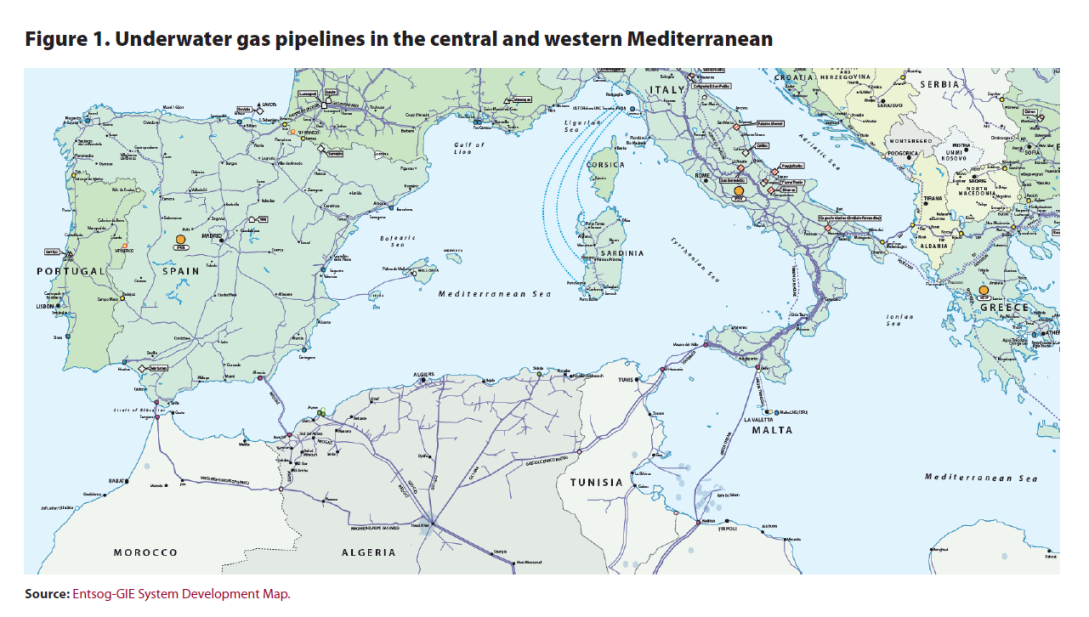

Italy and Algeria came to an agreement on May 11th 2022 whereby the volume of gas shipped via the TransMed (Enrico Mattei) pipeline would be increased from 21 bcm to 30 bcm by the end of 2023. This pipeline, which carries Algerian gas to Italy via Tunisia, thus acquires greater strategic importance.

Moreover, Italy is looking beyond gas. Stronger cooperation between Italy and Algeria should help stabilise Tunisia, not least because the first two countries see eye to eye on Libya. Tunisia faces an increasingly dire economic situation which Tunisian president Saied ignores at his political peril.

The war that began in Ukraine in February 2022 is reshaping international relations – in some sectors faster than others. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the field of energy, especially where gas and green energy are concerned. The European Union (EU) has underestimated the role natural gas would play in the energy transition since the turn of the century, irrespective of any given energy transition scenario. Hence the scramble to find more gas internationally once the EU decided to cut gas supplies from its major foreign supplier, Russia. The scramble was worsened by the fact that non-Russian producers of gas will not, for the next three years, have much extra supply capacity. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is even scarcer that piped gas.

Italy moves to diversify its gas suppliers

In the context of the looming gas crisis last autumn, Italy, which is very dependent on Russian gas imports, was quick off the mark and engaged with different gas producers from Qatar to Mozambique. It will continue to import gas in LNG form from Egypt and will shortly add Israel to its list of suppliers. In November 2021, it started negotiating its first contract to buy more gas from Algeria, ensuring that by the end of 2023 its North African neighbour will increase its throughput of gas via the TransMed pipeline from 21 billion cubic metres (bcm) per annum to 30 bcm. Earlier this year Italy’s state oil and gas company Ente Nazionale dei Idrocarburi (ENI) secured a broad range $1.5 bn contract with its Algerian counterpart Sonatrach to explore and develop new sources of gas, hydrogen, ammonia and electricity from renewable sources.

ENI has three strong cards to play in Algeria, which include: a) longstanding relations going back 60 years between Sonatrach and ENI; b) the first ever underwater gas pipeline from Algeria to Sicily through Tunisia and under the Mediterranean – an Italian engineering feat that is a tribute to the country’s sophisticated oil and gas industry, which spans every aspect of the hydrocarbon sector; and c) last but not least, the role ENI’s founder Enrico Mattei played in advising the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic in its difficult negotiations to gain independence from France at a time when France was attempting to prevent the recently discovered Saharan oil fields from belonging to the nascent country. Mattei died in an unexplained plane crash in 1963, a year after Algerian independence.

Since the First World War the history of the oil and gas industry is littered with coups, assassinations and wars, and not just in the Middle East.1 The conflictual relations between France, the United Kingdom, the US and leading Middle Eastern countries from Iraq to Saudi Arabia and Algeria offer the key to understanding many aspects of international politics over the past century. That history has often been written in blood and murder as major Western oil companies sought to retain control of the region’s vast oil and gas resources, only to be met by fierce reactions from Middle East producers. Seasoned observers of history are not surprised that the West’s increasingly fraught relations with Russia in recent years have ended in a brutal confrontation on oil and gas. It is too early to say which of the two sides will be the most damaged economically. But higher energy and food prices and the inflation they entail point to fraught international relations in the years ahead.

Italy’s increasing role as a gas hub

Italy is fast becoming the Mediterranean’s new gas hub. Three pipelines, from Azerbaijan, Libya and Algeria, bring gas to its southern shores. Floating storage and regasification units will allow more gas to be brought in from Egypt and Israel. If Germany decides to import more gas from Mediterranean producers, part of it could travel through Italy which can stock the stuff easily in the disused Po Valley gas fields.

Italy is looking beyond gas. In his recent discussions with Algerian president Abdelmajid Tebboune, Prime Minister Mario Draghi made clear that he was very interested in the well-armed North African country helping to stabilise Mali and other countries to the south of Libya. The Algerian head of state noted that both men were keen to help Tunisia at this point, although any financial support is likely to remain beneath the radar.

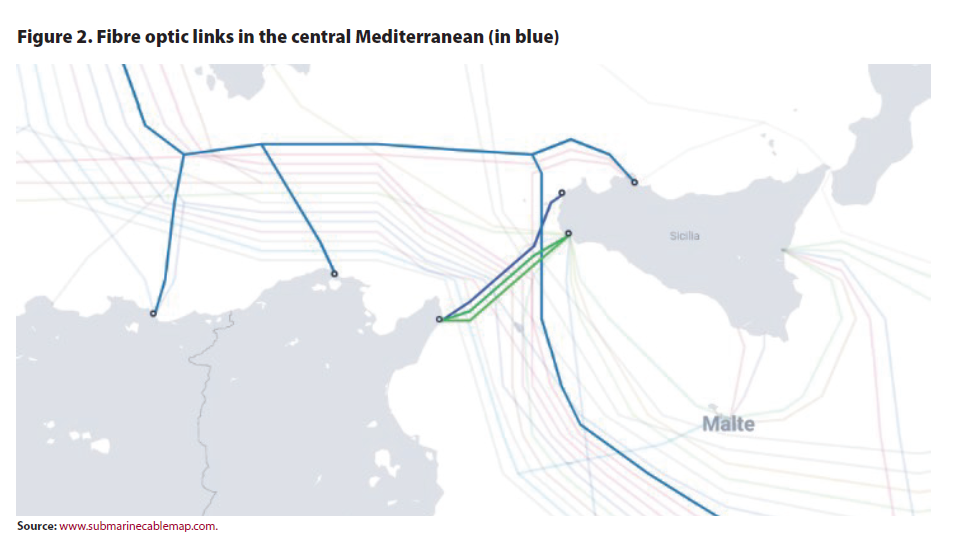

As Italy increases its Algerian gas imports to 30 bcm in 2023, the TransMed gas pipeline gains importance. Meanwhile, four fibre optic lines from Kelibia and Bizerta connect the Tunisian mainland to Italy and the SEA-ME-W4 cable that connects Asia to the EU. These could in the future carry solar-produced electricity from North Africa to Europe, running alongside the TransMed gas line from El Haouaria in Tunisia to Mazara del Vallo in Sicily. However, talk of a hydrogen pipeline between Algeria and Italy is premature.2

Source: www.submarinecablemap.com.

It is worth noting that Rome, Ankara and Algiers see eye to eye on Libya, whose UN-backed government they support against the eastern self-proclaimed Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar in Benghazi. He enjoys the support of Egypt, the Emirates and, to a lesser degree, France and Russia. France’s policy has left Italy very unhappy and torpedoed all attempts to forge a united EU policy on Libya. The recent appointment of Sabri Boukadoum as UN envoy to Libya strengthens Algeria’s hand. Just two years ago, Ramtane Lamamra, an Algerian diplomat who has since become his country’s foreign minister, was vetoed for the job by the US despite the very high respect for him internationally from Moscow to Washington, not to mention in African and European capitals.

Rebuilding Libya will eventually bring a great deal of work to Italian but also Tunisian companies which had invested a lot in Libya before 2011. Remittances from Tunisian workers in Libya helped stabilise southern Tunisia for decades. The stability of North Africa’s smallest country is essential for Italy as it helps allow the EU to control illegal immigration flows from Africa.

Complexities of intra-North African relations

Algeria has, since 2011, played a major role in stabilising Tunisia, whose president, Kais Saied, is reverting to a presidential constitution after years of a hybrid presidential–parliamentary system which made the country virtually ungovernable and much poorer. Saied’s suspension of parliament and the government on July 25th 2021 and the role Egypt played in advising him then has brought the army into domestic politics for the first time since 1956. It risks weakening the role it has held as neutral guarantor of the perennity of the state. Algeria is sensitive to US military influence but more concerned about the pressure Morocco and the United Arab Emirates are putting on Tunisia to recognise Israel. Algeria has helped Tunisia fight terrorism but its support has also been financial. Earlier this spring, it discreetly extended an estimated $1.5 bn loan to its western neighbour and reopened the frontier between the two countries, which had been closed by COVID-19 in 2020. Algerian tourists make a major contribution to Tunisia’s important tourist sector.

European capitals, not least Berlin, are openly supportive of Kais Saied and appreciate that branding him “authoritarian” while remaining silent about the fierce repression in Egypt smacks of hypocrisy. Tunisians have suffered a sharp fall in living standards since 2011, bewildered at the sight of a newly minted political class fiddling while Carthage burned. Popular support for Saied one year after he suspended the government and national assembly will be tested when the draft of the new constitution is submitted to referendum on 25th July. That said, Tunisia faces an increasingly dire economic situation which Saied ignores at his political peril.

Meanwhile, Morocco plays its own cards

As its star rises in the Mediterranean, Italy also benefits indirectly from the tense state of Spain’s relations with Morocco until last year and today with Algeria. Combined with Algeria’s traditional rivalry with Morocco, this has resulted in the closure of the pipeline which until last autumn carried Algerian gas to the Iberian Peninsula via Morocco, even as Medgaz has remained open, which carries Algerian gas directly to Spain. This closure was effective well before Spain’s change of position on the eventual status of the disputed territory of the Western Sahara. Algeria expressed its displeasure at the Spanish move but continues to value Spain as its second-largest gas client.

Spain, which has roughly twice the regasification capacity its domestic market requires, will only be able to contribute more to the EU’s overall gas security when France’s nuclear lobby lifts its longstanding veto on increasing the 7 bcm capacity of the gas line that carries gas northward across the Pyrenees. The Iberian corridor will then come into its own. Meanwhile, flows in the Maghreb–Europe pipeline restarted on June 28th 2022, with reverse flows of gas using the pipeline that closed on November 1st 2021 when Algeria cut off supplies to Morocco. The largest German energy company RWE has won the contract that allows Morocco to access Europe’s largest LNG market.

Meanwhile Morocco is developing other energy links beyond the EU with the United Kingdom. Energy tech pioneer Octopus Energy Group, in partnership with Xlinks, last May contracted to build the world’s largest subsea power cable to deliver renewable energy from Morocco to Devon in the southwest of the United Kingdom. This project fits with Morocco’s longstanding ambition to become a world leader in solar energy.

So, energy links are being redrawn

In the midst of these changes, it should not be forgotten that North Africa has done little to reduce its carbon imprint. Most of Morocco’s electricity comes from coal, and 100% and 90% of Algeria and Tunisia’s from gas, respectively. Climate change will hit the Maghreb hard, however its energy links with the EU are redrawn.

Although the stars are aligned to give Italy unprecedented influence in the central Mediterranean, other national actors in North Africa (Morocco) and outside the region (China and Turkey) are increasing their economic footprint and, in the case of the latter, their military presence in the Maghreb. France can only fight to retain what it considers its historic sphere of influence. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is accelerating a reshaping of the political and economic landscape of the central and western Mediterranean. The framework of economic cooperation put in place by the Barcelona Process in 1995 has given way to a quite different Mediterranean order – in the key field of energy at least. New and important energy transactions continue despite what a senior adviser to kings Hassan II and Mohamed VI once called “le bétisier sans fin des relations algero-marocaines”.3 What is occurring is less an economic decoupling between the EU and the Maghreb than a recoupling which is inserting Morocco (in energy but also financial terms due to the growing importance of Casablanca Finance City) into more global networks.

Notes:

1- Think of Hitler’s failed dash for the Caucasus oil fields in 1942–1943.

2- Pipelines carrying CO2 exist as a result of years of injection into gas and oil fields, but there is no experience of H2 pipelines, where specific issues of distance, material and compressor stations have yet to be solved. There is no market for hydrogen today, only greatly differing assumptions about pricing and cost. Any capital to finance such projects would thus have to come from the state, as no private sector bank or investor could justify putting up the necessary money.3- The never-ending stupid tit for tat of Algerian-–Moroccan relations.

3- The never-ending stupid tit for tat of Algerian-Moroccan relations

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24241/NotesInt.2022/276/en