Lone-Actor terrorism in Europe

Ovidiu Craciunas, PhD candidate, Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence (CSTPV), University of St Andrews and Diego Muro, Senior Lecturer in International Relations, Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence (CSTPV), University of St Andrews

Terrorist attacks carried out by lone individuals, with no direct affiliation to terrorist groups, referred to as lone-actor terrorism, represent a very distinct challenge for European societies. Generally lacking the complexity of plots carried out by terrorist groups, lone-actor terrorism can still cause numerous casualties and have significant impact.

How can we recognise lone-actor terrorism when we see it? What does this threat look like in the context of Europe? How can governments address this challenge and what can we expect in the future? This article provides a brief overview of the phenomenon in 21st century Europe.

Because terrorism is generally regarded as the “weapon of the weak”, used by groups in their struggles against stronger opponents, it should perhaps come as no surprise that lone individuals who feel powerless against the state or against their wider community also resort to this strategy in pursuit of their political goals. The case of the knife attack that occurred in the English town of Southport on July 29th, 2024, which made headlines not just in the United Kingdom (UK), but also in major news outlets across Europe, illustrates just how difficult merely recognising this phenomenon can be. On that day, a dance workshop attended by children between the ages of 6 and 11 became the target of a vicious attack carried out by the 17-year-old Axel Rudakubana, a British citizen, born in Cardiff, whose parents were originally from Rwanda. Three of the children attending the event died, while eight others and two adults, who had tried to intervene, suffered serious wounds. Within the context of the heated debate on immigration in the UK, many on the far right of the political spectrum quickly labelled this yet another example of terrorism carried out by someone who, according to them, had no place in the country to begin with. Large-scale protests and street violence across the country followed the incident, with attacks aimed at immigrant communities and police charging around 470 people for their roles in the riots during the summer of 2024.

While authorities did not initially regard the attack as a terrorist event, by late October 2024, prosecutors also brought terror charges against Rudakubana. Investigators discovered that he possessed a digital copy of an Al-Qaeda training manual, as well as a small quantity of ricin, a highly potent toxin, that could potentially be used as a weapon. The attacker had acted alone, he did not produce a manifesto, he did not make any statement to explain his motive, and his target did not hold any symbolic value that might reflect an ideology or reason for his actions. On January 23rd, 2025, Rudakubana was sentenced to a minimum of 52 years, the sentencing remarks noting that it is likely that he will never be released. But can this incident be regarded as a terrorist attack, or was it a different kind of extreme violence? The case highlights the strong impact such events can have, as well as the difficulties in merely recognising whether it was a lone-actor terrorism event or not.

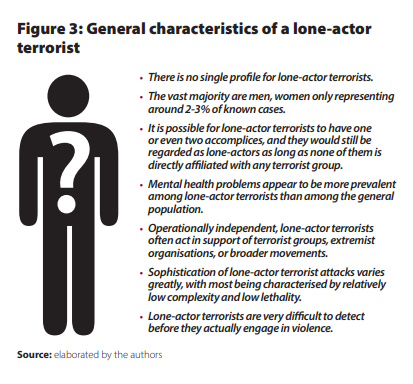

A better understanding of lone-actor terrorism is key to making sense of and ultimately preventing such events. While there is no universally agreed upon definition, according to some of the leading scholars researching this topic“a lone-actor terrorist is an individual who commits an act of terrorism on their own, neither part of nor formally directed by an organized group” (Holzer et al., 2022: 1).

A look at lone-actor terrorism incidents that occurred across Europe in the first two decades of the 21st century reveals how this threat has evolved and grown to become a challenge for governments and law enforcement agencies.

How big is the threat posed by lone-actor terrorists in Europe?

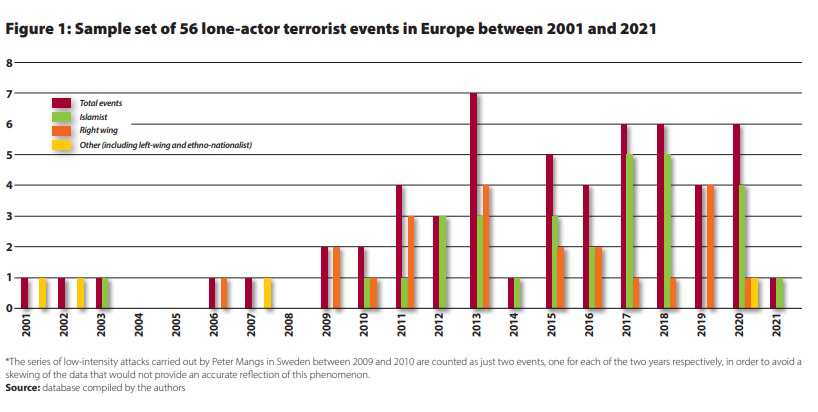

While there are no exact numbers for lone-actor terrorism events in Europe between 2001 and 2021 –the period of our research–, data collected from open sources does provide a reliable overview of what this phenomenon looks like and how it evolved over the years. Figure 1 was created based on a set of 56 terrorist attacks carried out by a total of 46 lone-actor terrorists. This is merely a selection of cases that received press coverage, and where it was possible to determine with reasonable certainty that the perpetrator was not part of an organization. It should not be regarded as showing all lone-actor terrorist events.

Figure 1 shows attacks that were carried out, as well as some failed or foiled plots, but cases were included only if there was no indication that the attacker received any help from or acted as part of any terrorist organisation. The data reveals how the number of lone-actor terrorist incidents began to slowly increase in 2009 and grow more sharply from 2011 onwards. Most lone-actor terrorists only carry out one single attack before they are arrested or neutralised by security forces. Exceptions such as Peter Mangs, responsible for 15 low-intensity attacks carried out in Sweden between 2009 and 2010, or Pavlo Lapshyn, responsible for one targeted murder and three bombings in the UK between April and July 2013, are rare.

This growth trend shown by the open-source data is also confirmed by the annual reports on terrorism published by Europol. These reports reflect how during the first decade of the 21st century organised groups were considered the main threats, with lone-actor terrorists only being mentioned briefly for the first time in 2008. By 2012 the report devoted a separate sub-section to this type of incident, pointing out that it was becoming more prominent among Islamists. The increased attention to lone-actor terrorism was also due to the events of the previous year, when the Norwegian Anders Breivik carried out a bombing in central Oslo, claiming eight lives, followed on the same day by a mass shooting on the island of Utøya, causing the deaths of another 69 victims, most of whom were adolescents. During this period lone-actor terrorist attacks were still relatively rare, with one prominent researcher noting that they were “black-swan type events” (Gill, 2015: 19). However, by 2015 the number of yearly incidents had increased, particularly the number of Islamist attacks, which were actively being encouraged by the Islamic State (abbreviated as IS, ISIS, ISIL or Daesh), a Salafist jihadist group that follows an ultraconservative branch of Sunni Islam. Europol reports show how the terrorist threat in Europe gradually shifted from attacks carried out by organised groups to attacks carried out by lone individuals, to the point that by 2018 all completed Islamist attacks in Europe were regarded as lone-actor terrorist events, and by 2020 the reports emphasised that the greatest threat came from lone actors and small cells.

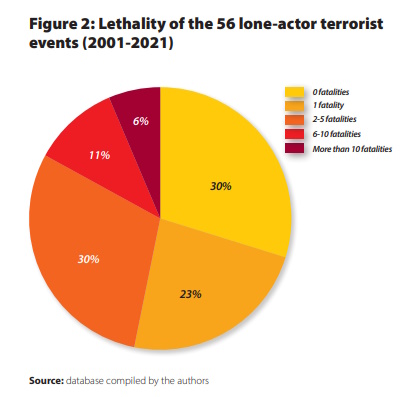

While it can be concluded that lone-actor terrorism increased significantly during the first two decades of the 21st century, the impact of such events does not present an existential threat to European states. In terms of sophistication, most attacks are carried out through very simple means, using knives, vehicles or firearms, and on some occasions explosives. Some attacks, such as the bombing at Brussels-Central railway station in 2017, when the home-made explosive device detonated but did not cause damage, can even be described as amateurish, while more complex and carefully planned attacks, such as the bombing in Oslo and subsequent mass shooting on the island of Utøya in 2011, are infrequent. Regardless of complexity, such attacks can still claim the lives of large numbers of victims, as in the case of the attack in Nice in 2016, when a truck was used as a weapon, being deliberately driven into crowds and ultimately killing 86 people.

Most attacks, however, cause few if any fatalities, but the ripple effects of such events should not be underestimated, as governments could be faced with backlashes, as in the case presented at the beginning of this paper. Islamist attacks can fuel Islamophobic sentiments among the wider population, which in turn has the potential to contribute to far-right violence and even acts of far-right terrorism, as illustrated by the cases of the previously mentioned Anders Breivik, or others such as Thomas Mair, responsible for murdering the British MP Jo Cox in 2016, or Stephan Ernst, responsible for murdering the German politician Walter Lübcke, in 2019.

How can we recognise an act of lone-actor terrorism?

Whether an incident is considered a lone-actor terrorist attack, depends on two aspects, which are not always straightforward. Firstly, the motivation behind the attack needs to be political, religious or ideological, or at least it must have some component that qualifies as such, while also aiming to influence a wider target audience, such as a government or a specific part of society, in order for it to be considered a terrorist event. The motivations of lone-actor terrorists can often be quite complex, with personal grievances factoring in, and they can be much less clear than the motivations of terrorists who belong to organised groups. The case of the mass shooting at Jokela High School in Finland in 2007 demonstrates how complex the motivation behind an act of lone-actor terrorism can be. The incident was essentially a school shooting, with personal grievances being a key factor in the motivation of the 18-year-old Pekka-Eric Auvinen, as he had been bullied consistently by fellow students. However, the materials he had left behind also revealed a political motive, or at least a political component to his motive, including the hope that his actions would inspire others and spark a “revolution against the system”. This would qualify his attack not only as a school shooting but also as a terrorist event. Contrary to this example, the case of the attack carried out by 22-year-old Jake Davison in Plymouth, UK, in 2021 demonstrates how certain events might appear to be terrorist attacks, only for more in-depth investigations to reveal an absence of any political motive. In this case, while the perpetrator was a follower of misogynistic incel ideas prevalent online, the attack was the result of a particularly violent domestic incident that spilled into the street, leading to a mass shooting and the subsequent suicide of the perpetrator.

Secondly, the perpetrators must not be affiliated with any existing terrorist group, and they must not be the recipients of direct aid for the planning, preparation or the execution of the attack. In this sense, some attacks can initially appear to have been carried out by lone-actor terrorists, only for subsequent investigations to uncover that the attacker received support from or was even a member of a terrorist group, such as in the case of the attack on a Christmas market in Berlin, Germany, in 2016, when the perpetrator, the 24-year-old Anis Amri, was later found to have had direct connection to an Islamist cell as well as a known recruiter for the Islamic State. In rare cases, an attack can be carried out by more than one person and still qualify as a lone-actor terrorist event, such as in the case of the murder of an off-duty British soldier in London in 2013. The two Islamist attackers, Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale, were not part of any terrorist group, and they had not received any outside help.

Furthermore, it should also be noted that lone-actor terrorism incidents can very easily fly under the radar of authorities and researchers when their impact is too small to be picked up by the press, when the legal systems of the countries where the events occurred do not treat them as terrorism, or when there is simply insufficient evidence to determine a political motive or whether the attacker acted independently from existing terrorist organisations. This is perhaps illustrated by one case that occurred in Bucharest, Romania, in 2022, when a car loaded with incendiary materials deliberately crashed into the gate of the Russian embassy, after which the driver set himself on fire. While it was clear that he had acted alone, his posts on social media appeared to suggest at least some political motive. But prosecutors quickly ruled out terrorism, focusing instead on personal problems the perpetrator was facing, and labelled the event a suicide.

Lone wolf vs lone-actor terrorist

A quick glance at historical cases of politically motivated violence in Europe reveals that there were instances of lone-actor terrorism as early as the late 19th century, and likely even before this, although such events were historically not very common. Examples of such early lone-actor terrorists include Vera Zazulich, who in 1878 attempted to assassinate the governor of St. Petersburg; Luigi Lucheni, who in 1898 murdered the empress of Austria; and Gaetano Bresci, who in 1900 assassinated the king of Italy. These cases would certainly not have been recognised as lone-actor terrorism until much later, because the term itself is much more recent than the phenomenon.

The term lone-wolf terrorist entered circulation much earlier than the term lone-actor terrorist, but both are used interchangeably, with American scholars generally preferring the first and European scholars the latter. In this context, the term lone wolf emerged from the writings of American white supremacists and far-right activists during the early 1990s. By the mid-1990s, Tom Metzger, a former Ku Klux Klan member and founder of the White Aryan Resistance (WAR), published two essays on his website, entitled Begin with the Lone Wolves, and Laws for the Lone Wolf, bringing considerable attention to the term (Spaaij, 2012: 25; Gill, 2015: 5). By the time it caught the attention of scholars, it had already entered use among journalists and various commentators. This origin led some terrorism researchers, such as Borum, Fein, & Vossekuil (2012: 390) and Gill (2015: 11), to reject the term lone wolf terrorism. As research on this topic picked up during the 2010s, the term lone-actor terrorism gradually became more widely accepted among scholars, but without managing to completely supplant the older term.

Are lone-actor terrorists different from terrorists affiliated with groups?

In general demographic terms, lone-actor terrorists are older and have a greater chance of being unemployed or not being involved in relationship or marriage compared to terrorists affiliated with organisations. One important aspect where these two types of terrorists show differences is that of mental health. Rates of mental health problems appear to be significantly higher among lone-actor terrorists when compared to terrorists affiliated with groups, as well as when they are compared to the general population. There is also some indication that this aspect might also be a factor in their decision to resort to terrorism alone, as they are unable to meet the often military-style requirements that some groups have in place for would-be members.

Finally, it should also be pointed out that there are cases where the line between these two groups is very blurred. For example, Khairi Saadallah, responsible for a mass stabbing in the UK in 2020, had been a member of a Syrian terrorist group named Ansar al-Sharia during his adolescence, while another lone-actor terrorist, Stephan Ernst, responsible for the murder of a German politician in 2019, had been a member of various local neo-Nazi groups during his youth and had been in contact with members of Combat 18, a neo-Nazi terrorist organisation. However, by the time they carried out their attacks they had long abandoned these groups and there was no indication they maintained contact with them. Both had spent time in prisons prior to the attacks in 2020 and 2019, and had gone through deradicalisation programmes (Ernst even married and became a father after his release), managing to convince authorities they had been successfully rehabilitated.

Why act alone?

Government surveillance and counterterrorism measures evolved significantly during the first decade of the 21st century, especially following the infamous September 11th, 2001, attacks carried out by Al-Qaeda in the United States. Complex and meticulously thought-out attacks in Europe, such as the train bombings in Madrid in 2004 and the bombings on public transport in London in 2005, also contributed to measures that made it much harder for Islamist groups to carry out similar large-scale attacks. As a result, Al-Qaeda’s strategy shifted from large-scale attacks carried out directly by members of the organisation or its various cells to encouragement of individuals to carry out smaller-scale attacks on its behalf, a strategy that was later also adopted by the Islamic State. A similar process had played out earlier in the United States, where white supremacist groups found it increasingly difficult to operate under the pressure of government surveillance, leading to the emergence of the notion of “leaderless resistance”, according to which small independent cells were more effective at waging guerilla-style warfare. By the early 1990s, this notion had evolved into the idea that a single individual, with sufficient motivation, training and resources, could also carry out acts of terrorism.

However, this is only part of the reason why some individuals engage in lone-actor terrorism. A closer look at the histories of such individuals reveals how there are also cases when they try to join existing groups or even attempt to create their own. Anders Breivik had unsuccessfully tried to fit into a number of far-right groups and online circles where he believed that others would share his views, but consistently failed. As a result, he decided to create his own organisation, “The Knights Templar”, in which he was the only member.

As such, the decision to resort to lone-actor terrorism instead of joining a terrorist group can be either a voluntary one, resulting from a desire to reduce the chances of being discovered, or an involuntary one, resulting from the inability to join any existing group.

What have we learned?

The case of Axel Rudakubana was not designated as a terrorist attack; prosecutors labelled it a “mass killing”, with the sentencing note pointing out that the perpetrator’s culpability “is equivalent in its seriousness to terrorist murders”. At the time of writing, there was no publicly available information suggesting any political motive behind the 17-year-old’s vicious actions, making this incident more similar to school shootings than lone-actor terrorist attacks. Its potential to contribute to new instances of violence, as illustrated by the large-scale protests that followed the attack, should not be overlooked. The incident illustrates just how difficult it can be to distinguish lone-actor terrorism from other forms of extreme violence carried out by lone individuals. Unless future investigations or Rudakubana’s own future statements reveal any new details to suggest the contrary, his case can be regarded as an example of what is not lone-actor terrorism.

Nonetheless, as this article has shown, there has been no shortage of examples of violent incidents in recent decades that certainly meet the criteria required to be regarded as lone-actor terrorism. This phenomenon evolved significantly in Europe between 2001 and 2021, becoming more prevalent from 2010 onwards. It was a favoured strategy among both Islamist and far-right terrorists, with very few examples of left wing, ethno-nationalist or single-issue lone-actor terrorism. It took many forms, from targeted stabbings, such as the one carried out by Ali Harbi Ali in the UK in 2021, resulting in the death of British politician David Amess, to mass stabbings, such as the attack by Abderrahman Bounane, in Finland in 2017, resulting in two deaths, to mass shootings, such as the one carried out by David Sonboly in Germany in 2016, resulting in nine deaths and the death of the attacker, to incidents where vehicles were used as weapons, as in the case of Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel, whose actions in France in 2016 led to 86 deaths. The vast majority of attacks were carried out by men, with one of the very few exceptions being the case of Roshonara Choudhry, responsible for the attack on British politician Stephen Timms in the UK in 2010. Lone-actor terrorist events varied significantly in terms of their complexity as well as their lethality, ranging from relatively simple knife attacks such as in the previously mentioned case of Choudhry, to the more complex bombing in Oslo and shooting on the island of Utøya, carried out by Anders Breivik in Norway in 2011.

The tragic nature of lone-actor terrorist events, particularly for those who have lost loved ones or who have suffered life-changing injuries, is beyond any doubt. For broader societies and European countries, however, the threat is not an existential one but should still be addressed as effectively as possible. When combating this phenomenon, European decision-makers should take into consideration the following:

• As a phenomenon, in the context of Europe, lone-actor terrorism is likely here to stay.

• Lone-actor terrorists are more difficult to identify and trace than those affiliated with groups and therefore pose different challenges to law enforcement.

• The encouragement of lone-actor terrorism can become a viable strategy for terrorist groups that lack the capability to directly carry out attacks inside Europe.

• There is no one-size-fits-all solution, and it is important that governments do not overreact by limiting the personal freedoms of citizens or by imposing intrusive surveillance measures.

• When lone-actor terrorist attacks do occur, governments should also be on the lookout for ripple effects that might follow, including the radicalising effect they might have on certain segments of the population.

• Counterterrorism agencies should be more proactive instead of being merely reactive, while also keeping an eye on new technologies that might be used by extremists.

There is also a concerning trend - at least in the context of the UK, where an increasingly large number of minors have been referred to the country’s deradicalisation programmes - that could suggest that extremists might be starting to engage in violence at younger ages. The accessibility of extremist materials online is a contributing factor, as the dissemination of such materials is very difficult to limit, especially considering the growing number of different social media platforms.

Finally, with regard to technology, just as the invention of dynamite in 1867 allowed a level of destruction previously impossible for any single individual to achieve on their own (a moment in history which actually coincided with the rise of a wave of anarchist terrorism), the emergence of new technologies today might also hold currently unimagined destructive potential for future terrorists. The appearance of artificial intelligence could provide new opportunities for extremists, while 3D printing has already raised alarm bells because it offers the possibility to create weapons, including firearms.

Considering these challenges, law enforcement agencies across Europe will certainly have to remain on the lookout for lone-actor terrorists in the future and will be faced with increasingly ingenious ways to carry out attacks.

References

Borum, R., Fein, R., and Vossekuil, B. “A dimensional approach to analyzing lone offender terrorism”, Aggression and Violent Behaviour, vol. 17, no. 5 (2012), p. 389-396.

EUROPOL. “EU Terrorism Situation & Trend Report (TE-SAT)”. Annual reports 2002-2024 (online) https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-events/main-reports/tesat-report [accessed 20.01.2025.]

Gill, P. Lone Actor-Terrorists – A Behavioural Analysis. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Holzer, J. C., Dew, A. J., Recupero, P. R. Gill, P. Lone-Actor Terrorism – An Integrated Framework. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022.

Spaaij, R. Understanding Lone Wolf Terrorism. New York: Springer, 2012.

All the publications express the opinions of their individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CIDOB or its donors

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24241/NotesInt.2025/314/en