The world in 2021: ten issues that will shape the international agenda

Text finalised on December 11th 2020. This Nota Internacional is the result of the collective reflection of the CIDOB research team in collaboration with EsadeGeo. Coordinated and edited by Eduard Soler i Lecha, it has benefited from contributions by members from both organisations (Hannah Abdullah, Anna Ayuso, Jordi Bacaria, Ana Ballesteros, Pol Bargués, Moussa Bourekba, Anna Busquets, Carmen Claudín, Carme Colomina, Emmanuel Comte, Carlota Cumella, Anna Estrada, Francesc Fàbregues, Oriol Farrés, Agustí Fernández de Losada, Blanca Garcés, Eva Garcia, Andrea G. Rodríguez, Séan Golden, Berta Güell, Marc Ibáñez, Esther Masclans, Óscar Mateos, Sergio Maydeu, Pol Morillas, Francesco Pasetti, Oriol Puig, Enrique Rueda, Olatz Ribera, Héctor Sánchez, Ángel Saz, Cristina Serrano, Eloi Serrano, Marie Vandendriessche and Martina Valls) as well as by several individual partners of CIDOB.

Uncertainty. A common term for describing the future, but 2021 will give it new meaning. The outbreak of the pandemic in 2019 has spread a feeling of vulnerability across the planet. It has changed our daily lives with a speed and intensity that has reminded us of the fragility of what we thought strong and the malleability of what we thought immutable. We are now much more aware of the immediacy and forcefulness with which unexpected changes can take hold. The pandemic has been a powerful reminder of the weaknesses of our warning systems and our lack of preparedness for handling future crises. If COVID-19 has been a kind of examination, collectively we need a resit.

2020 was a year of perplexity. The shock’s intensity and a lack of recent precedents of similar magnitude resulted in confusion, doubt and poor problem-solving capacity. However, 2021 will be a year of action, of individual and collective decisions whose impact will stretch far beyond the year itself. 2021 will be a fork in the road, a critical juncture, a time of risks, but also of opportunities that may or may not be seized. When we reflect in ten years’ time, tracing the origin of the dynamics shaping interpersonal relations and international relations, it is likely that we will look for their origins in the crisis of 2020 and the decisions taken in 2021.

2020 was a year of destruction, but 2021 could be synonymous with construction or reconstruction. Since the virus emerged in Wuhan, many lives and jobs have been lost and trust in certain institutions has dissipated. News stories about treatments and vaccines will raise hopes and could produce signs of recovery sometime in 2021. But will everyone benefit? What should be done with those left out of vaccination programmes, with individuals and territories suffering from crises other than health, and those at risk of falling behind given the accelerated change the pandemic has brought about? The pre-coronavirus world was already deeply unequal, and the decisions made in 2021 will either correct or widen those inequalities on multiple levels.

Many would include the Trump factor in the list of vectors of destruction even beyond 2020, believing his four-year tenure has eroded democracy inside and outside the United States, as well as trust in institutions. Encouraging news about vaccines and their economic repercussions and a different face in the White House will generate excitement but, once again, not for everyone. How will the authoritarian regimes that have counted on the favour of the leader of the US react? Will Trump supporters cause trouble for the new Democratic administration? What if the Biden–Harris duo fails to bring about the changes that both their base and many of their international partners expect of them? Can confidence in multilateralism be regained, and if so, how?.

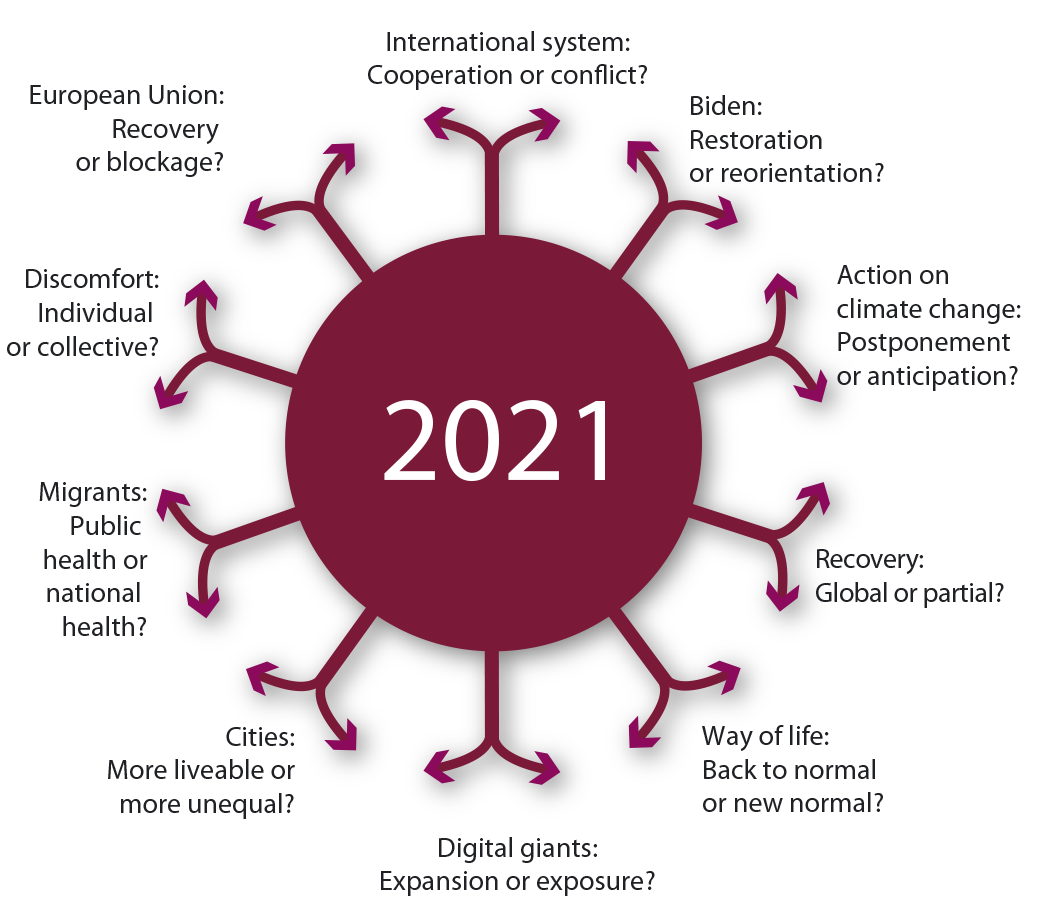

One question will repeatedly arise in 2021’s multi-level (re)construction exercise: Is a return to the normal possible or even desirable? This question will permeate all manner of debates: on international cooperation and conflict, the United States’ role in the world, the economic recovery, the environment, immigration, the urban agenda, managing unrest, as well as everyday issues like work, mobility and consumption, and the validity and adaptability of the European model to these changes.

2021: A Year of Choices

Author: CIDOB Elaboration

1. International system: Cooperation or conflict?

The dysfunctions in global governance have been laid bare by the pandemic: contested international bodies, the tensions triggered by a China looking to assert its place in the world, and a liberal order undermined by those who created it. The United Nations Security Council provided the clearest example. Faced with one of humanity's greatest challenges, it took until July 1st to agree Resolution 2532 on COVID-19, after three months of deliberation and blockage while 10 million cases accumulated in healthcare systems.

The health emergency has given rise to two contradictory responses. On the one hand, cooperative responses have been revived. Recalling that the pandemic is one of many challenges that can only be addressed globally, cooperation networks have been strengthened at regional level – in Africa, for example – as well as between cities around the world. On the other hand, there has been no shortage of protectionist and even nationalist reactions, and (re)emerging powers are showing renewed interest in expanding their areas of influence, adding healthcare to their diplomatic arsenal.

In 2021, vaccines will be incorporated into these dynamics. Getting the vaccine to lower-income countries and conflict areas is an economic, political and logistical challenge that can only be achieved with improved international cooperation such as COVAX. Governments, international organisations and private foundations will all need to be involved. Simultaneously, vaccine geopolitics will emerge. In 2021, China and Russia will use the supply of their vaccines in the same way they used the provision of basic medical supplies in 2020. Having acquired more doses than they need, the European Union and its member states will try to recover the ground lost in 2020 by donating some of their surplus.

One of the many side effects of COVID-19 has been and will be the worsening of humanitarian crises due to increasing poverty, declining availability of international aid and logistical difficulties delivering it. Yemen is an extreme case, but the trend is widespread. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) warns that, as of October 2020, it had received only 38% of the funds it needs. The FAO warned in its 2020 annual report of a rise of between 83 and 132 million malnourished people in the world. The Munich Security Conference preparatory report describes the situation as a “polypandemic”: along with the regression in terms of development, poverty and famine, it noted increased repression, institutional fragility and various forms of violence becoming entrenched. UN Women similarly warned of a “shadow pandemic”, as the victims of gender-based violence were found to be more vulnerable when sheltering at home. Another form of violence that has adapted to the pandemic is organised crime, which an International Crisis Group report describes as strengthening and extending its control over peoples and territories in Latin America. Humanitarian crises may also be exacerbated in 2021 by increasingly frequent and devastating natural disasters or by the thawing of conflicts that were frozen in the second half of 2020 in the Caucasus, the Horn of Africa and the Sahara.

Accumulating crises will continue to fuel debates over why some countries and societies are better prepared to tackle the pandemic and its effects: authority, cohesion, values? In 2021 we will see which factors and models lead to faster, fairer and more sustainable recoveries. Along with the debate on authoritarianism, perhaps reinforced by the Chinese Communist Party’s centenary, discussions will touch on whether populism has hit rock bottom following Donald Trump's less-resounding-than-predicted defeat.

The new administration in the United States will raise hopes of the revitalisation of a multilateralism of variable geometries. In some cases, global organisations and agendas will regain centre stage, with the WHO playing a key role. In others, the lack of comprehensive solutions and dysfunction in the mechanisms that should facilitate them – like the constant blockages in the Security Council and World Trade Organisation (WTO) – will facilitate progress at regional or interregional level and around shared thematic agendas.

2. Biden: Restoration or reorientation?

Politically speaking, 2021 will begin on January 20th with the Biden–Harris inauguration. It will be seen as a time of change, of high hopes for some segments of US society, but also of frustration for the over 74 million who voted for more of Donald Trump. This will not be a regular transition. That Joe Biden is very likely to be a one-term president and that Kamala Harris is likely to be an unusually prominent vice president will make this leadership change look exceptional. Outside and inside the United States, three debates will recur: Is it possible to depolarise the United States? Is Trumpism defeated or rearming? Does the new administration aspire merely to restore the United States as the main power in the system or to change its direction?

Multilateralism is one field where the restoration drive will be most evident. The appointment of John Kerry and the promises made on the campaign trail leave little doubt that the new administration will prioritise the climate agenda. When outlining his priorities during the transition, Biden has gone beyond reiterating his desire to rejoin the Paris Agreement. The US shall “lead by example” in tackling global warming, and reach climate neutrality no later than 2050. This is one of the areas where the restoration drive will have to overcome possible vetoes in the Senate. Other returns will take place, such as the reactivation of its commitment to the WHO and the United Nations Population Fund. By contrast, the new team has been less explicit about re-joining UNESCO and the United Nations Human Rights Council.

The State Department and its officials will also require refurbishment if US diplomatic capabilities are to be strengthened. A more structured foreign policy will be implemented that will help increase the predictability lost at a stroke by the outgoing president’s tweets. The Iran nuclear deal (JCPOA), in particular, will be the point of convergence for the new administration’s restored multilateralism and greater faith in diplomacy and negotiation. Biden and his team will have to choose between two strategies: rejoin the deal or try to renegotiate it. The margins for renegotiation are tight if a deal is to be struck before the June 2021 Iranian presidential election. Resurrecting the nuclear deal with Iran could be one of the first contributions to global security, but it will be an arduous process, fraught with mutual distrust, and will have to reckon with the strategies of multiple actors seeking to block it in Washington, Tehran and other Middle Eastern capitals.

As part of the “deTrumping” process, we will also see democracy and human rights return as a foreign policy priority. Trump did not hide his affection for authoritarian leaders. But, while the United States will continue to deal with these regimes, Biden will not praise Egypt’s al-Sisi as “my favourite dictator” and “beautiful letters” will not be with Kim Jong-un. Instead, the new administration will seek ways to reaffirm itself as a defender of freedoms. One proposal on the table for 2021 is a summit of democracies. It will be worth seeing who is invited. Human rights violations in both hostile countries and notional partners and allies will be reported more vehemently. Among the great unknowns of 2021 will be whether such pressure is able to reverse the harassment of critical voices in these countries, and to what extent it boosts protest movements in Russia, China or the Arab world.

Notwithstanding this desire for restoration, domestic and international factors will favour reorientation. At home, the president will strive to rebuild basic social consensuses, ease the most extreme polarisation and focus efforts on managing the social emergency caused by COVID-19. This will also involve constant exertions to keep the president’s majority together, given the weight and mobilisation capacity of the Democratic Party’s progressive wing, while reaching out to the moderate representatives of the Republican Party.

In international affairs, the main driver of reorientation will be China. An article in Foreign Affairs by Biden in March, when he was a Democratic candidate, gives some clues as to his possible views on this subject. He sketches out an economically and technologically more powerful China and a relationship between the two main global powers characterised by competition and rivalry. Biden will defend US interests against China as vigorously as Trump did, especially when it comes to trade and intellectual property issues – he has defined this as foreign policy in the service of the American middle class. What will distinguish Biden from his predecessor is that he will much more actively seek alliances to address this challenge in both the transatlantic and Indo-Pacific spheres.

So, should we expect more interventionist policy? Biden and his team have an internationalist profile, but must reckon with US society’s weariness about the past two decades’ costly military adventures and their disappointing results. But it is not just the US vision and preferences that count, so too do the manoeuvres of other actors in the system. As friends seek to discern what to expect from this administration, enemies will feel for the red lines. Attention must be paid to the manoeuvring not only of state actors but also of terrorist movements eager to humiliate a United States in retreat or in need of regaining visibility in the year of the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks.

3. Action on climate change: Postponement or anticipation?

In 2021 we will see how green the first steps of the economic recovery are, what impact the Biden administration’s arrival has, what willingness exists to reach agreements, and how they translate into commitments around November’s COP26 in Glasgow. Will they build on the announcements by powerful economies like China, Japan, South Korea and the European Union of steps to achieve climate or carbon neutrality?

The pandemic has produced a sense of unprecedented vulnerability all over the planet, albeit to varying degrees. Climate activists will take advantage to demand immediate and effective action against the effects of climate change. For years, experts have warned that the thawing of the polar icecaps would lead unknown bacteria and viruses to reappear for which there is no treatment or immunity. The WHO, along with other organisations, have identified a direct link between declining biodiversity and infectious diseases. The pandemic has also shown how exceptional circumstances can alter mobility patterns, with flying falling by up to 90% in some cases and consumption shifting towards local produce and shorter food supply chains. This will bolster the arguments of those who say that a successful transition to a more sustainable way of life can be achieved if we want it, and that the fight against the pandemic has been a dress rehearsal for tackling the climate crisis.

On the other hand, COVID-19's emergence has quarantined movements like #FridaysForFuture (FFF) and Extinction Rebellion (XR), which rose to prominence in 2019 and began to influence the political agenda, especially in industrialised countries. The pandemic has also produced short-term needs for action that may have side-lined the climate emergency and stimulus plans have been established that – with exceptions like the European Union's Next Generation – omit or even weaken environmental considerations. Despite efforts to raise awareness about recycling and reuse, the pandemic has increased disposable plastic use in both healthcare and other areas of consumption. The city of Wuhan produced 240 tonnes of medical waste compared to its usual 40; the United States foresaw that in two months of 2020 the same amount of waste would be generated as in the entire previous year. In 2021 new attempts will be made to regulate single-use plastics and already-adopted regulations will enter into force in the EU, Costa Rica – Latin America’s leading environmental country – and Thailand, among others.

Along with regulation and individual consumption patterns, new technologies will raise hopes in the climate field. Hydrogen may be one of the key themes in 2021. Some industrial conversion to hydrogen would help meet emissions neutrality target, it has great potential for fertilisers and offers huge advantages in terms of storage. These processes will be led by the major industrialised economies and will feature strong collaboration between the public and private sectors as part of their post-pandemic reindustrialisation plans. But we will also see countries in the Global South exploring the potential of hydrogen technology, either for domestic consumption or for export. Morocco, already a pioneer in renewables, will also sped up its hydrogen plans, taking advantage of momentum from the bilateral agreement with Germany. India, an energy-dependent country with rising demand, is enthusiastically embracing hydrogen technology, while Chile has unveiled plans to start producing green hydrogen in 2021.

4. Recovery: Global or partial?

Data on the immediate economic cost of COVID-19 will be published in the first months of 2021. It will be time to take stock of the damage. Although stock markets have recovered a significant share of the losses since March 2020, largely driven by successive good news stories about vaccines and treatments, a return to pre-pandemic activity will be much slower to arrive and will above all be uneven. It will also be a fragile recovery. Any negative health developments, such as vaccination processes failing or the virus mutating could shatter the hopes that began to build in late 2020.

GDP Annual Growth (1980-2020): More Economies in a Deeper Fall.

Source: International Monetary Fund (October 2020).

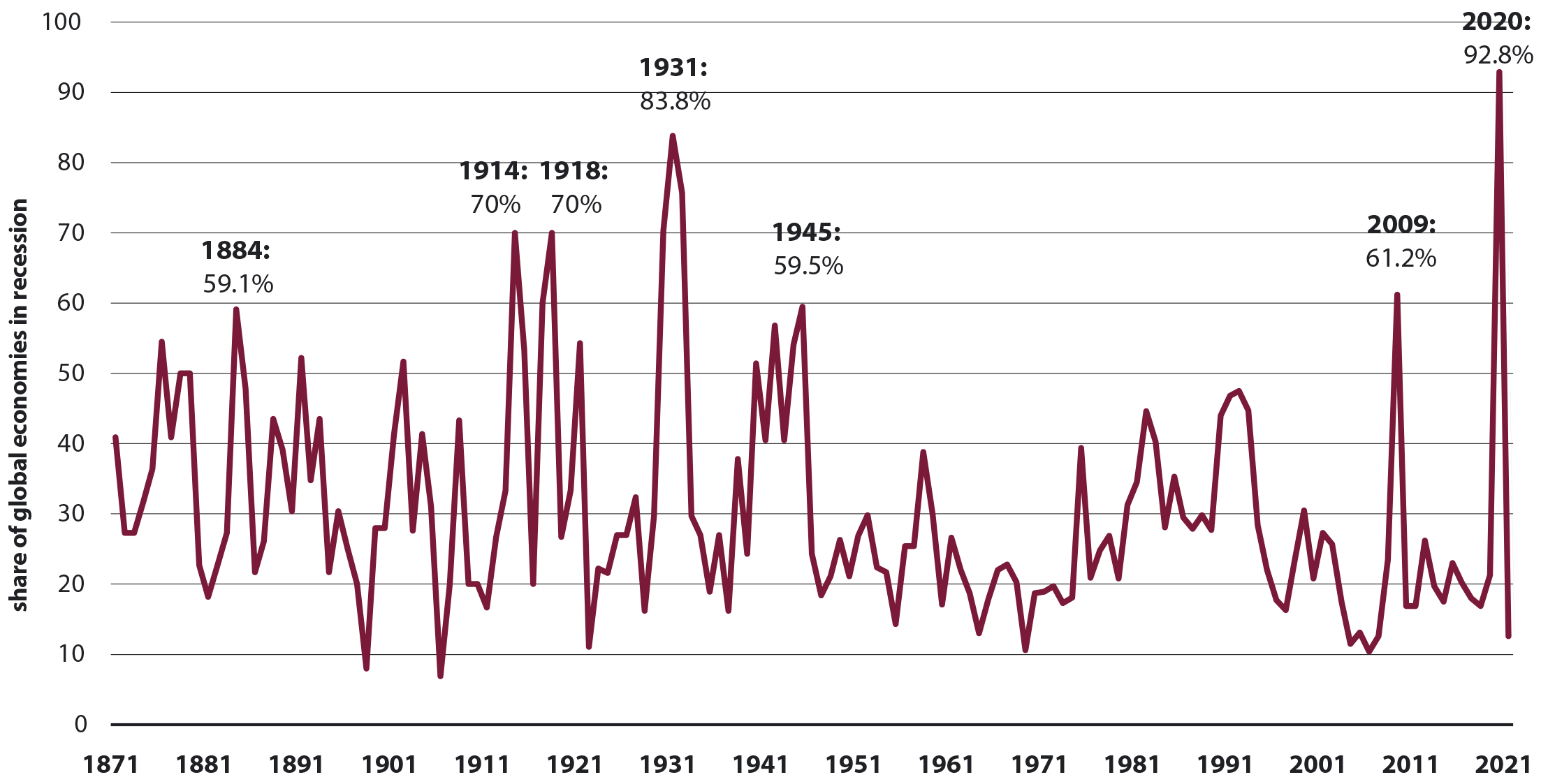

Economies in Recession (1871-2020): A Record High Number

Note: Projected data for 2020 and 2021. Economies in recession are defined as those that experience a contraction of their annual per capita GDP.

Source: World Bank (June 2020).

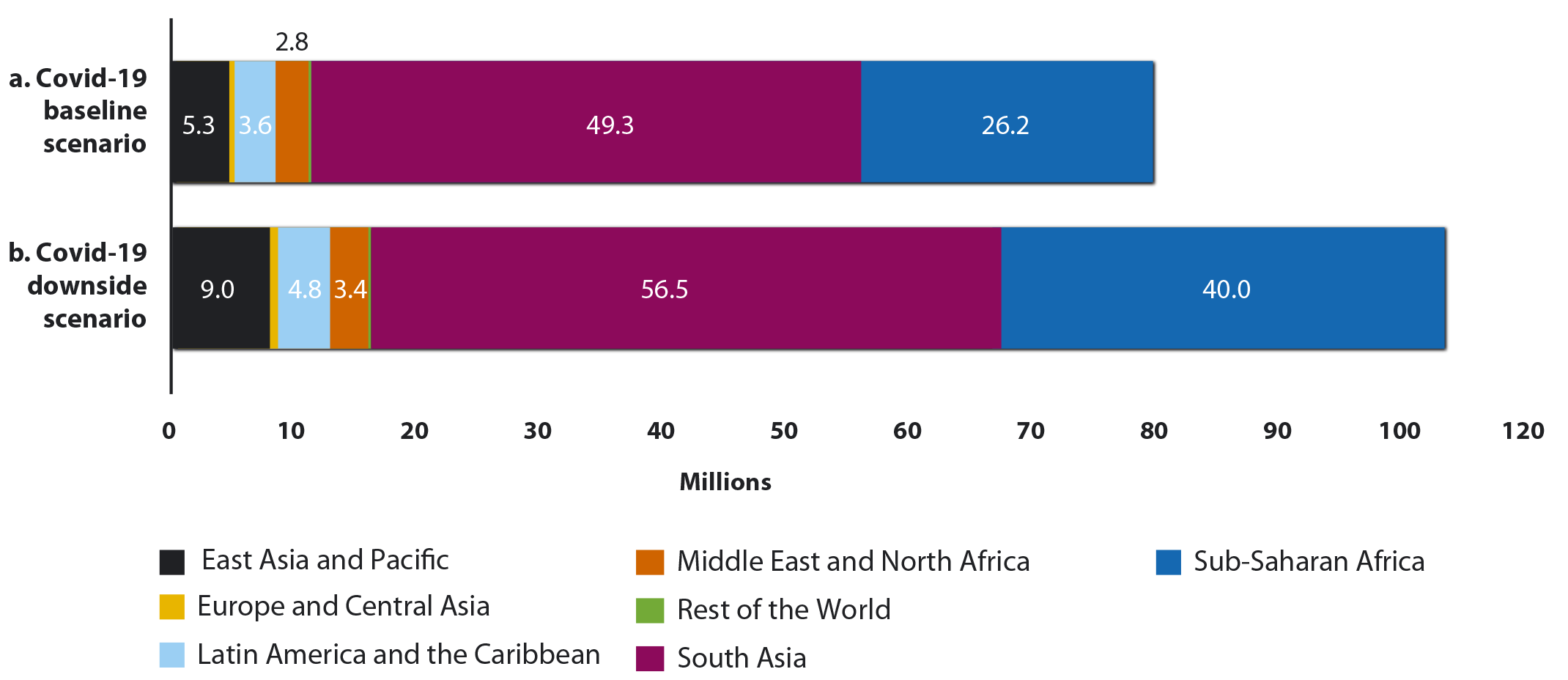

Beyond the economic growth figures, the big issue of 2021 will be the distribution of wealth and income. Inequalities at international level and within individual societies are nothing new. But the pandemic has starkly revealed the varying capacities within and between countries both to fight the virus and to withstand the measures needed to tackle it. All pre-existing inequalities have widened. Even the progress made on gender equality in recent years has been compromised because women have tended to bear a greater care burden, and many have seen their careers cut short. A particularly revealing fact is that while they account for only 39% of the workforce, 54% of the jobs lost in 2020 were held by women. Education gaps have also widened between children in families equipped for distance learning and those who are not, considerably raising the risk of higher rates of school dropout. Equally alarming is the World Bank forecast that 150 million people could be pushed into extreme poverty in 2021, in clear contradiction with the first Sustainable Development Goal.

Additional Poor at the US$1.90-a-Day Line in 2020 per Covid-19 (millions of persons)

Source: World Bank, Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020, Reversals of Fortune, (October 2020).

If the pandemic’s impact has been uneven, so will be the recovery. As 2021 begins, economists debate whether the recovery will be V, U or W-shaped. But the letter that best illustrates the new year's economic outlook is probably K, given the likely bifurcation of recoveries. Following the trauma of 2020, some sectors and individuals – most likely a minority in quantitative terms – will recover quickly and end 2021 with improved wealth and well-being. These sectors will benefit most from the greater liquidity generated by the implementation of new stimulus plans, as well as from rates of saving rates that are higher in absolute terms but unevenly distributed. Middle-income economies, like those in Latin America, and low-income economies, such as most African countries, may experience liquidity crises. In other words, the gaps will grow between those with access to credit and those without, and between the different levels of preparedness and adaptability to technological transformation.

For broad swathes of the economy and society the recovery will be very weak and even non-existent, especially among those who have lost their jobs, their businesses and in the worst cases their homes. This may give rise to the situation theorised by Albert Hirschmann in 1973 as the “tunnel effect”, as those frustrated at being detained in a lane of stalled traffic watch those in the neighbouring lane move forward and begin to emerge from the pandemic tunnel.

China will represent one of these different speeds, as its dissociation from the other major international economies continues. The country where the virus originated was one of the few that continued to grow in 2020, and in 2021 – when the 14th five-year plan enters into force (2021–2025) – it is expected to grow by over 8%. The case of China, as well as the emergency measures adopted in many other countries, have prompted the re-emergence of the state's role in the economy.

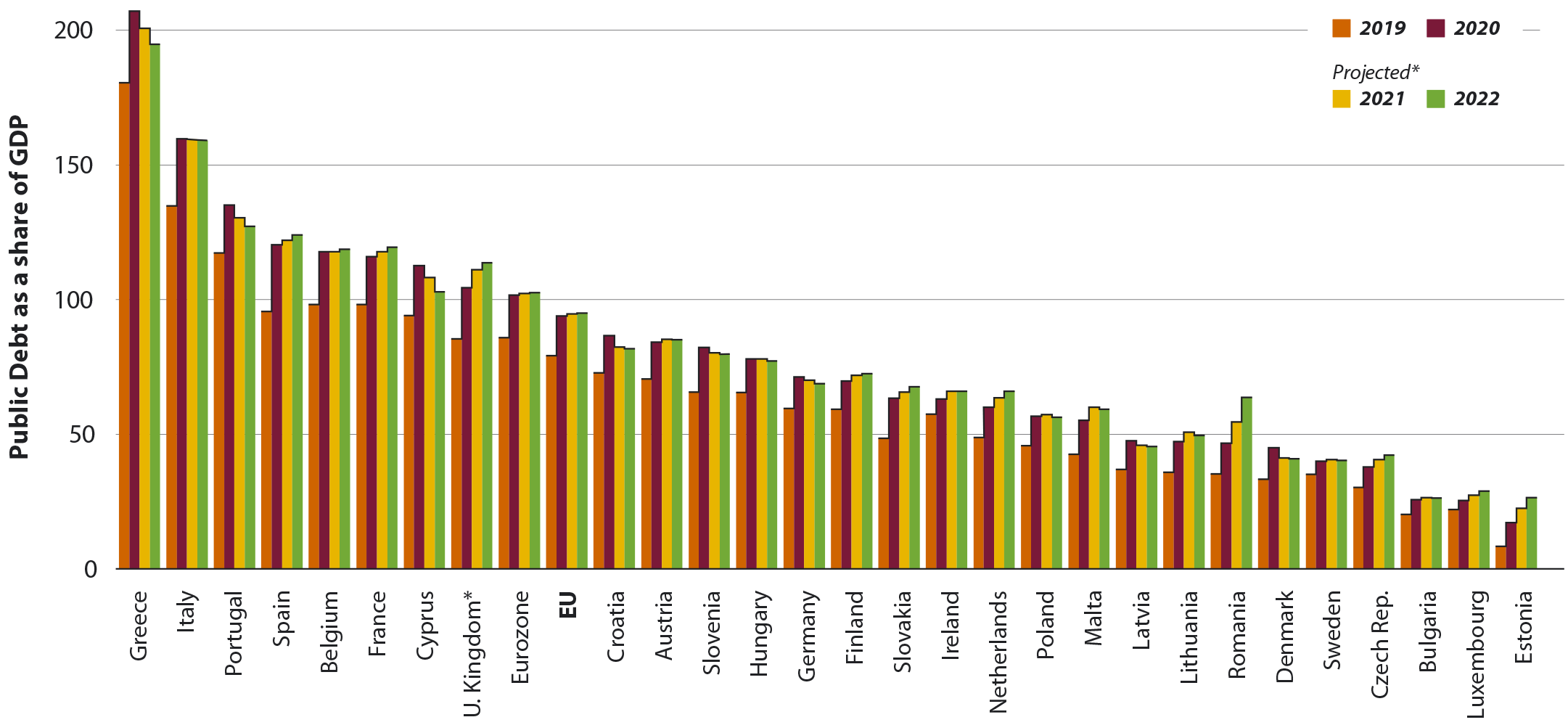

One of the consequences of the state returning to the centre has been higher public debt. In the euro area it has reached 95% of GDP, increasing by over ten points in the three main southern European economies of France, Italy and Spain. The new EU budget and reconstruction funds, which will begin to be implemented in 2021, will strengthen investment and public spending policies. The IMF and World Bank have also advocated an expansionary fiscal policy and increased financial support. The proponents of austerity find themselves cornered, but it remains to be seen if the victory will be more than temporary. The major financial institutions now seem confident that future growth, the result of fiscal expansion and better economic governance, will enable the debts to be repaid. In 2021, the debate will also intensify over the goals of the reindustrialisation plans that will be launched, the labour market’s adaptation to digitalisation processes, and the desirability of promoting production relocation – especially for strategic products – or of shortening global value chains.

Public Debt Grows Among the EU Members (share of GDP, 2019-2022)

Source: EUROSTAT (2020).

Note: (*) The United Kingdom will leave the EU in January 2021.

5. Way of life: Back to normal or new normal?

Of the changes brought by COVID-19, the fastest were in the ways we work, travel, consume, relate and even conduct international relations. Will these also be the deepest and longest-lasting changes? To what extent might a new normality condition the international agenda?

Diplomacy may be among the first areas to return to normality, given the vast limitations of “zoom diplomacy”, the security vulnerability of virtual meetings, and the memory of the dreary 75th anniversary of the United Nations. Various get-togethers were postponed in 2020, among them the G7 summit in the United States and the bi-continental summit between the countries of the European Union and the African Union. When health conditions permit, we will see international agendas quickly stuffed with summits, official trips and pending visits. Although, at a more technical level, mechanisms for remote information exchange and dialogue are likely to be normalised.

In other areas of everyday life, the changes may have been deeper and, although it may not seem so at first glance, they will impact the international agenda. One of the clearest is remote working. As with so many other issues, major divergences exist between countries, between economic sectors and between income levels. A study published by Gartner during the first lockdown showed that 88% of companies in the United States offered, favoured or required telecommuting. But, by the same token, a study from the University of Chicago showed that while 97% of legal work and 88% of that in the financial field could be done from home, face-to-face was the norm in other areas, with only 3% telecommuting in transport and 1% in the primary sector. It also found that, in general, jobs that could be performed remotely were better paid.

At the international level, the consolidation of remote working methods, even after the health crisis has passed, may encourage networking and the creation of teams based in different cities and even continents, promoting inclusion and diversity. It could also speed up the relocation of some administrative work to places with lower wage costs. Above all, it will drive the rise of cloud data storage up the list of key issues for 2021. Large companies will compete fiercely for shares of the data storage business, energising the debates over digital sovereignty and increasing vulnerability to cyberattacks and industrial espionage carried out on government orders or by non-state actors.

Face-to-face work and the progressive but uneven recovery of economic activity will see some of the lost mobility return. In the second half of 2021 we will have a sense of whether we are in the process of returning to the pre-pandemic norm in terms of business trips, major trade fairs and sporting events as they were understood pre-COVID-19, or whether we will tend to travel less and organise these activities differently. The holding (or not) of the Tokyo Olympics, the Dubai Expo 2020 and the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona will set the tone. But countries that have made airport infrastructure and flag carriers a form of soft power and international positioning like Turkey, Qatar, Singapore and Morocco will play a big part in this change.

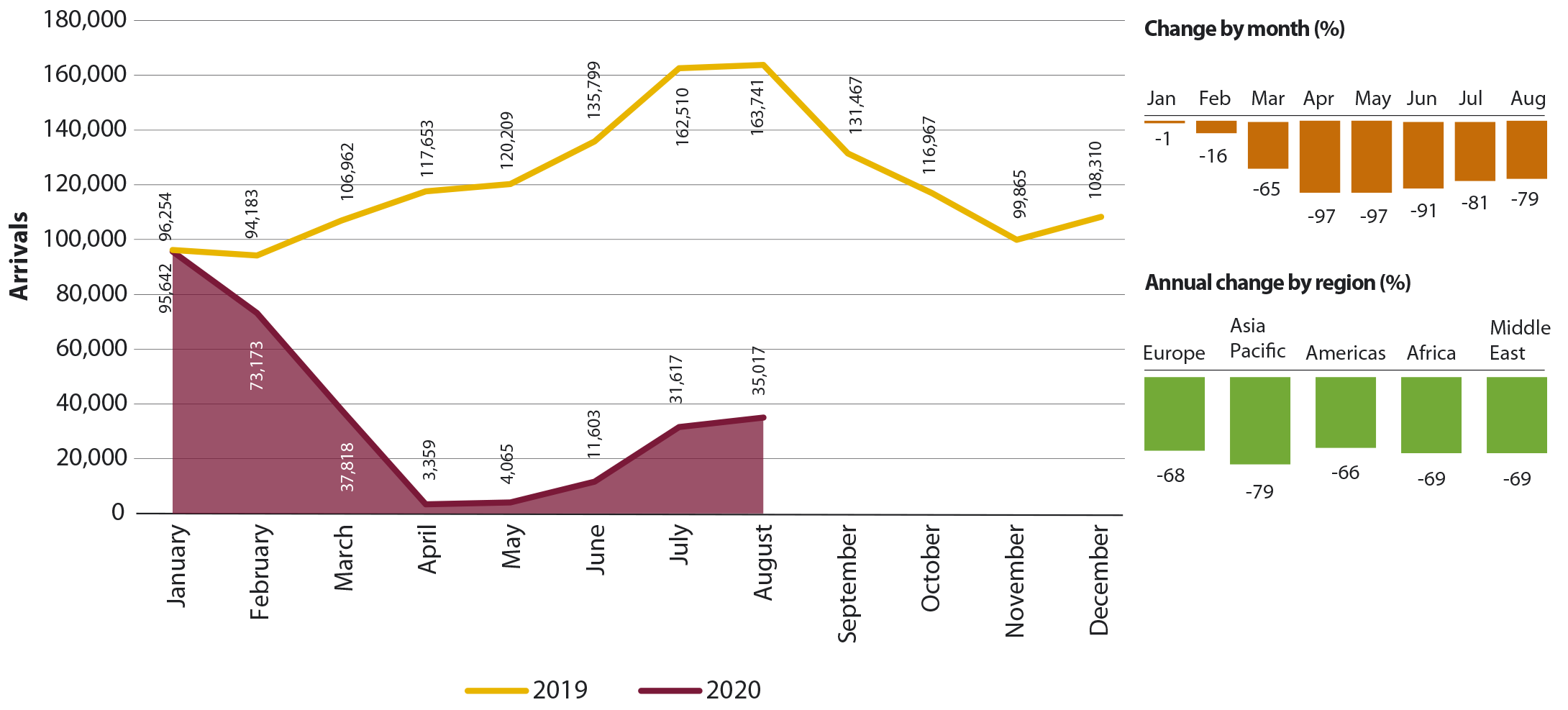

Tourism was another of the sectors most affected by the pandemic. According to the World Tourism Organization barometer, international tourist arrivals fell by 70% in January–August 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. That means 700 million fewer international tourist arrivals a loss of $730 billion in revenue – more than eight times the loss recorded in 2009 due to the impact of the global economic crisis. That the prospects for recovery in the first half of 2021 do not seem encouraging leaves some economies and territories that overly depend on tourism in a very delicate situation. Thailand is a paradigmatic case, where the unprecedented contraction of its economy fuelled a new wave of protests in late 2020. It is a precedent that will raise alarms in other tourist destinations in the Mediterranean and Caribbean. Alongside this immediate concern, many of these countries will have to address the debates on tourism sustainability and economic recovery and diversification strategies, while at the same time handling the social consequences of any change.

In the second half of 2021 we will have a sense of whether we are in the process of returning to the pre-pandemic norm in terms of business trips, major trade fairs and sporting events as they were understood pre-COVID-19, or whether we will tend to travel less and organise these activities differently.

The Collapse of Tourist Arrivals (arrivals, 2019-2020)

Source: World Tourism Organization (data until August 2020).

Consumption is another area where habit changes have accelerated. The blow has been especially hard in sectors like catering, culture and retail. In terms of the model, it has also called into question the attractiveness of the large commercial spaces that have come to shape half of the world's urban planning. Numerous articles and reports argue that traders should not bet on a return to pre-pandemic normality but commit to realigning their business model. What are the challenges at international level? The coronavirus crisis has given a major spur to the delivery industry and the phenomenon of delivery riders has placed the focus back on working conditions, with governments and policymakers all looking to each other for the best solution. As we shall see below, lockdown has also been a springboard for the digital giants, increasing the urgency for governments to control monopolistic tendencies, ensure consumer protection and prevent fiscal haemorrhaging. Achieving this would require some degree of international coordination.

6. Digital giants: Expansion or exposure?

Digitalisation is a mega-trend that is hard to reverse and in 2020 it suddenly accelerated. In 2021, giants like Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft will continue to dominate, but the fastest growth will be among their Chinese rivals and new companies that emerge almost from nothing. In 2019 Tik-Tok became popular and in the midst of the pandemic Zoom grew from 10 million daily meetings in December 2019 to 300 million in April 2020. It is impossible to know who will surprise us in 2021. Meanwhile, a number of alternative platforms emerged in 2020, such as bookshops pooling resources to compete with Amazon. While unlikely to pose a quantitative threat to the big tech giants, it will be interesting to observe whether any such initiative is able to become consolidated.

Digital expansion leads to greater exposure and, as a result, greater scrutiny by public opinion and governments. In 2021 the exposure of the digital giants will be reflected in three areas: taxation, competition and sovereignty.

The rapid growth and the nature of the activity has so far made it possible to exploit fiscal engineering to the maximum. But states need revenues more than ever to cover the social costs of the pandemic and recovery plans. Taxing digital services provides an opportunity. So the clash of interests that had begun to take shape before COVID-19 broke out has acquired a new urgency. In 2020, attempts to reach a transatlantic agreement in this area were derailed, despite an agreement being made in principle at the G7 in Biarritz the previous year. A one-year extension was agreed to continue negotiations on digital rates in the OECD framework, but if no progress is made EU countries will continue alone, which could create tensions with the new US administration.

One point where the Biden and European digital agendas could overlap is the need to limit oligopolistic behaviour. Although not one of his main campaign issues, Biden’s policy is expected to differ from that of the laissez-faire Obama administration, meaning this could be one of the few areas in which bipartisan cooperation flourishes.

Digital sovereignty was a term that was gaining popularity before the pandemic, and the trend towards the creation of two spheres of technological influence pivoting around the United States and China is likely to continue. How the European Union, India, Japan and South Korea respond to being left out of this race will also become clearer. The EU will deploy its regulatory arsenal. Its main novelty is the approval of the Digital Services Act (DSA), which seeks to protect the single market and preserve and improve consumer rights, as well as contemplating, among other measures, preventing digital giants from using the data collected unless they make it available to smaller platforms. In terms of sovereignty, 2021 should be a year in which European cloud data storage alternatives like Gaia-X are boosted, an initiative led by France and Germany. In many countries of the Global South the debate will be different: it will concern data colonialism and will take the form of a fight in which they are not actors but the battlefield.

In developing countries in Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, one of the novelties that awaits us in 2021 may have a longer future: the digital yuan will come into operation. It will fluctuate less than cryptocurrencies and will be backed by a central bank. Taking advantage of increased digital transactions in times of pandemic, the adoption of this digital currency has two objectives. Within China, it aims to reduce the dominance of Alibaba and Tencent in digital payments. Beyond its borders, it seeks to expand its area of economic influence. This currency will be attractive to consumers in countries with precarious financial systems, depreciating currencies and difficulties making online purchases. In both cases, its popularity will give China much more information about preferences and consumption patterns inside and outside its borders. The rest of the world will pay close attention to the experience of the digital yuan and its success could accelerate plans for the introduction of other digital currencies, intensifying the debate on the opportunities and risks of a digital euro.

7. Cities: More liveable or more unequal?

In 2020, cities were at the forefront of the fight against the pandemic. Population density was a key factor in the spread of the disease. Just over half of the world’s people live in urban areas, but according to United Nations 90% of registered cases have been in urban environments. Cities are also the locations of the research being carried out to fight the pandemic and the main healthcare infrastructure. In 2021, cities will remain on the frontline, with extra focus on managing the economic and social effects of the pandemic. The clash between two opposing forces will intensify: on the one hand, recentralisation to handle an emergency situation, and on the other, greater demands for autonomy and resources for decentralised cities and territories to move towards economic and social recovery.

The outbreak of the pandemic has strained the current urban model. Local authorities and social movements now demand more liveable, healthier cities with more sustainable individual and collective mobility. To move toward this change of urban paradigm, cities look to each other for inspiration and hope to emulate good practices that have worked hundreds or thousands of miles away. Cities for Global Health, an online platform launched by governments, institutions and civil society that brings together 657 initiatives from 34 countries and 105 cities, is a good example of this dynamic. In 2021, cooperation and exchange networks will become more important, while individual competition between cities will be accelerated to see which comes up with the most innovative solutions and highest levels of citizen acceptance. In its least healthy version, this competition will result in disputes between global cities to access more funding or better position themselves in the post-pandemic recovery.

In many countries, the pandemic has strengthened social innovation (as it did after the 2008 crisis), with solidarity initiatives and community and neighbourhood efforts multiplying. Numerous mutual support networks have emerged, both at national level (such as İhtiyaç Haritasıin Turkey, Mutual Aid in the United Kingdom, Territoires Engagés in France and Territorios en Acción inArgentina) and at local level (Mutual Aid NYC in New York, the Rede Solidária de Lisboa in Lisbon, andin the São Paulo favela of Paraisópolis and in La Paz). In 2021, we will see to what extent local governments exploit the potential of these practices to strengthen the institutional response to the social and health crisis. This will depend on city governments’ ability to foster lasting policy co-production relationships with communities and social groups. The pandemic has also further underlined that cities are centres of knowledge creation and 2021 will be a year of consolidation for the global scientific networks that connect research teams (who are associated with the cities hosting their institutions).

However, along with the opportunities, new risks have emerged that could take particularly virulent forms in 2021. Social unrest will grow in cities as the pandemic deepens inequalities. In the centres and in the suburbs most affected by the crisis, the urban space will be the setting for recurring expressions of unrest, which will in many cases lead to riots and clashes with police forces and even between groups with conflicting interests. Demands relating to access to housing, economic opportunities and health workers’ working conditions are likely to characterise protests in 2021. If and when the pandemic is under control, any economic recovery, far from alleviating these tensions, may raise them, as any route out of the crisis is likely to be as unequal a process as the crisis itself, or even more so. The visibility of this inequality in an urban environment will generate still more frustration and even violence.

Some will see this situation as an opportunity to reverse the depopulation of rural areas. However, in quantitative terms the prevailing trend will be different. First, peri-urban spaces are becoming more attractive, making metropolitan governance more important. Second, overcrowding housing in low-income neighbourhoods will increase and, in the most extreme cases, also homelessness levels can rise. Third, the large cities of the Global South will continue to attract people and grow, especially in informal settlements.

To all this we must add that the digital divide has widened. The post-pandemic context will further reinforce inequality between connected territories and those that, metaphorically, remain in the dark. For example, in the United States, only 65% of citizens living in rural areas have access to high-speed internet compared to 97% in urban areas. In 2021, broadband and 5G coverage will be as important as electrification processes and the building of basic transport infrastructure at other times.

8. Migrants: Public health or national health?

Each immigrant or asylum seeker may be a virus carrier. So goes the new xenophobic argument used by those who demand watertight borders, stricter controls and express repatriations. With internal border closures normalised to control the pandemic, it will be easier to demand the building of walls and the application of exceptional measures to keep borders sealed and to repel arrivals.

One of the paradoxes of 2021 is that the societies that will seek security through border closures are those that will also try to attract foreign medical and healthcare staff. This is the case, for example, of the United Kingdom, which has automatically extended all visas for migrant doctors and nurses that expired before October 1st 2020 by one year. That the founders of BioNTech, the company that has worked with Pfizer on a COVID‑19 vaccine, are Turkish immigrants to Germany will be used as a counter-argument by those advocating for a more flexible migration policy.

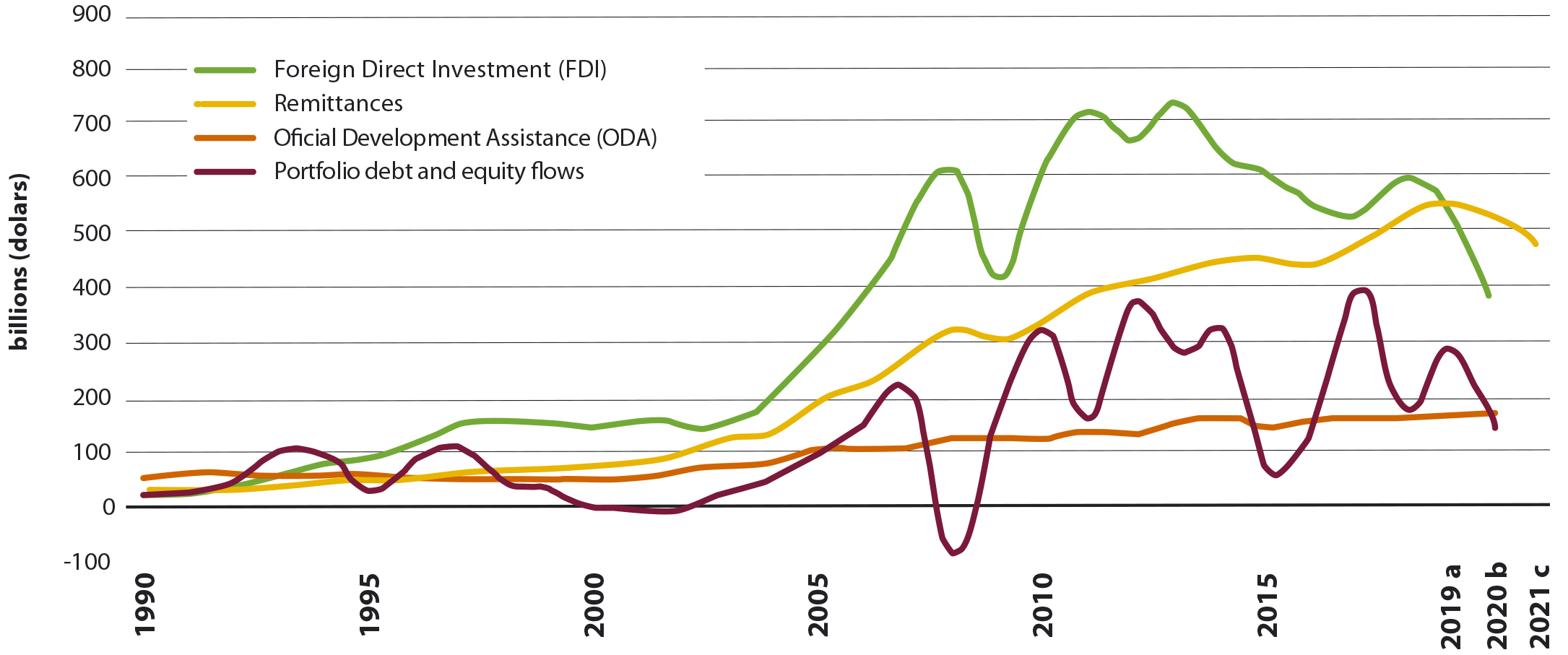

The desire to close borders will face increased migration pressure from countries that have suffered employment loss in sectors like tourism, the overexploitation of natural resources or an accumulation of structural problems like Algeria, Nigeria, Venezuela and the Central American republics. To these difficulties must be added falling remittances expected for 2021 which, according to World Bank, could be 14% lower than 2019. To understand the significance of this, in 2019 the volume of remittances exceeded that of foreign direct investment. Should the recovery drag on, it is likely that in 2021 we will see new expulsions of foreign workers from Gulf countries and tensions rising in South Africa about migrants from neighbouring countries.

Remittance Flows Towards Middle and Low Income Countries (1990-2021)

Note: (a) Estimation; (b) Projection. Source: World Bank/KNOMAD and IMF.

With regard to international migration, 2021 will not differ much from the previous years: mismanagement, short-termism, dehumanisation, sporadic crises, securitisation, erosion of rights and an attempt to move the real border further and further from the official one. On the other hand, addressing how resident foreigners fit within society will present a genuine dilemma, whether their status is irregular or not. It is a debate that will not only be conducted in moral terms, but also in terms of interest and rationality.

The pandemic and its consequences are producing ambivalent effects. On the one hand, part of the population is more vulnerable to the politics of hate; on the other, large migrant populations working in certain sectors have become more visible, such as cleaning staff, caregivers, home delivery workers, smallholders, employees in the food sector and seasonal agricultural workers. These workers are beginning to be recognised as essential parts of the economic and social machinery. Will this translate into more inclusive policies? Will the recognition last, as with the incorporation of women in the labour market and the recognition of universal suffrage after the two world wars, or will it prove fleeting? And, if it happens at all, will it be limited to the medical field or will it be understood that the degradation of working, housing and educational conditions among part of society also constitutes a public health problem?

On the other hand, the pandemic intensifies the discussion in European countries, America, the Middle East and the rest of Asia about the risks to public health of having sections of society that are neglected or living outside official channels. Irregular immigrants are one of the most easily disregarded or deliberately excluded groups. The context of a health emergency led the state – and with it the citizens – to rediscover something apparently obvious: that it should reach all households, should register everyone residing in its territory, that it is not easy to separate “their” problems from “ours” and that “their” health is everyone’s health. The mass vaccination processes foreseen in 2021 will make this even more evident. But the possibility exists that certain groups will argue that nationals should have preference, inviting contrasts between partial and exclusive national healthcare models and those that are universal, inclusive and public.

With regard to international migration, 2021 will not differ much from the previous years: mismanagement, short-termism, dehumanisation, sporadic crises, securitisation, erosion of rights and an attempt to move the real border further and further from the official one.

9.Discomfort: Individual or collective?

Ten years have passed since the Arab and African springs, the indignados in Spain and the Occupy movement in several Western countries. 2021 will be a time to look back and consider the results of these emancipatory protests and what is left of the hope they managed to generate. It will also be a time when the major unrest that spilled onto streets in 2019 from Hong Kong to Latin America via Baghdad, Algiers and Beirut is “unconfined”. In a context of pandemic and mobility restrictions, some may believe that the cycle of protests has ended. But as 2021 progresses we are likely to see that it was merely on pause and any attempts to make permanent the restrictive measures applied during the pandemic will only increase the agitation.

In general terms, the pandemic has aggravated and spread the discord that caused people to take to the streets in 2011 and 2019. Scientific voices warn that more than a pandemic, COVID-19 is a syndemic, insofar as social factors are indispensable to understanding its uneven impact. Its effects have also given new arguments to the climate movement and the feminist struggle, two causes of major demonstrations before the onset of the virus that have remained dormant for much of 2020. In its own way, 2021 will also be emotionally intense. The excitement of being able to defeat the virus and regain some lost normality will be overlaid with the discomfort among large swathes of the population, those left behind at the end of the crisis, and in the most extreme cases, the rage of those for whom the health, economic and social wound of the pandemic remains open.

As the use of public space is regained the protests will return and set about trying to recover lost ground. They may even start before then. Indeed, various movements sprung up in the second half of 2020 – the powerful #BlackLivesMatter movement in the United States, feminist protests in Poland, pro-democracy movements in Belarus, expressions of political unrest in Peru and Guatemala, and #EndSARS in Nigeria. If we have learnt anything from studying previous protest cycles it is the importance of emulation. The awareness that everyone has suffered the same blow and the accelerated consumption of information on social media may make processes of emulation more likely in 2021. But we also know that, while a common core of discomfort exists, geographical and temporal contexts affect its expression. The major African countries, from Algeria to South Africa and Nigeria to Ethiopia begin 2021 facing great uncertainty. Countries that have suffered from the collapse of tourism such as Thailand, Senegal and those in the Mediterranean have also seen the pandemic revive prior unrest. In Russia, the opposition’s capacity to mobilise is one of the great unknowns of 2021; the authorities’ capacity for repression may be counted upon.

Despair and frustration, in part due to the lack of results from previous protest cycles, as well as increased repression by security forces, mean that there is a clear risk of this new cycle of protests becoming more violent. Another issue worth watching in 2021 is whether the solidarity networks coordinated in 2020 at local level become mobilisation structures. It will also be interesting to see whether the numerous electoral processes planned in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa act as multipliers of tension or can instead be mechanisms for channelling the unrest.

One of the characteristics of the protest dynamics of 2021 is that they may be expressed as demands for groups within society rather than demands on society as a whole. This group dynamic may pitch minorities against the majority, majorities against the minority, or express territorial, generational or even trade union grievances. Vaccination campaigns, which must for logistical reasons be conducted in a segmented way, may prove a source of additional grievance.

The discomfort will also have an individual dimension, as months of confinement, diminished social interaction and its replacement by virtual contacts, and an often silent mental health crisis take their toll. This individual unease may deepen previous dynamics such as violent radicalisation or the crisis of intermediaries, which in many countries manifests itself as distrust in institutions, the political class, the media, experts and civil society associations. It is also a breeding ground for conspiracy theories and other forms of misinformation that have been growing in the heat of the pandemic .

10. European Union: Recovery or blockage?

The European Union has a project for itself and for the international system. The question is whether internal and external conditions in 2021 will favour its promotion. For 15 years the European integration project has faced a string of unprecedented crises and challenges like the United Kingdom's departure. This pattern of continual crisis means debates on whether lessons have been learned from previous crises will continue throughout 2021. It will also be judged on whether it responds ambitiously, generously and promptly not just to the pandemic but to the recovery strategies.

Pandemic management and recovery plans will not be the only factors conditioning the European agenda and its ability to influence the global agenda. First of all, there is the electoral calendar. In 2021 and 2022 a political impasse may arise in two phases. Germany will go to the polls in October 2021 and Chancellor Merkel will leave office after more than 15 years in power. Meanwhile, the pre-election atmosphere will begin to take hold in France, given its double appointment with the polls in spring 2022. The second factor is relationships with neighbours. In 2020, tensions with Russia have persisted and have increased with the United Kingdom and Turkey for different reasons and to different degrees. The turbulence in its eastern and Mediterranean neighbourhoods must be added to this. The European Union may find itself blocked by the obstructive attitude of some of its members, by a lack of self-confidence or by the accumulation of crises both within it and the immediate environment. Or, the contrary may be true, with 2021 being a year of recovery, momentum and transformation.

This dilemma will have two fronts. The first is preserving the essence of European integration. Among many other things, the EU is a union of democracies and the rule of law, but it faces a challenge if it is to head off and reverse illiberal tendencies on the inside. It is also a space of freedom of movement. Here the obstacle is fear, embodied in 2021 by issues as diverse as terrorism, the pandemic and poorly managed migration flows.

The second front concerns transformation. The European Union has always aspired to transform itself and the countries around it and even to set standards that can be applied to the other component parts of the international system. The pandemic has given impetus and even meaning to the Green Deal and the digitalisation agenda. These will be also be priorities on the EU's external agenda in 2021 at, for example, the bi-regional meetings scheduled with Africa and Latin America.

At the intersection between the agendas of preservation and transformation we find two other challenges: the economic recovery and the desire for greater strategic autonomy. In terms of recovery, talk will shift from resources towards priorities and implementation mechanisms, and many of the elements outlined in previous sections will be central: in which sectors should we invest? Is a return to the past possible? How can growing inequalities and accumulating unease be reversed? How can territorial cohesion be assured? What role should cities and regions play in the management of reconstruction plans?

The pandemic has also given a boost to the idea of strategic autonomy, one of the pillars of the 2016 Global Strategy. In 2021 we will see if the discussions to promote reshoring strategies to shorten and bring supply chains closer, especially of vital products, translate into concrete initiatives and whether these are designed with consideration given to the reindustrialisation of the EU or whether they also incorporate neighbours in eastern Europe and the Mediterranean basin. We will also see if it is feasible to simultaneously treat China as a partner, competitor and rival, or whether Europeans are forced to choose between one of these modalities. Naturally, not everything will depend on EU preferences, but also on what Beijing and Washington do.

The prospects for 2021 for the international system and the European construction clearly converge on one point: the pandemic has exposed weaknesses and contradictions, but it has also been a powerful reminder of high levels of interdependence and the need for cooperation and solidarity. 2021 provides an opportunity that may or may not be seized. Perplexity is no longer an option, and in a year with multiple forks in the road, the intensity of processes of change oblige us to choose a direction.

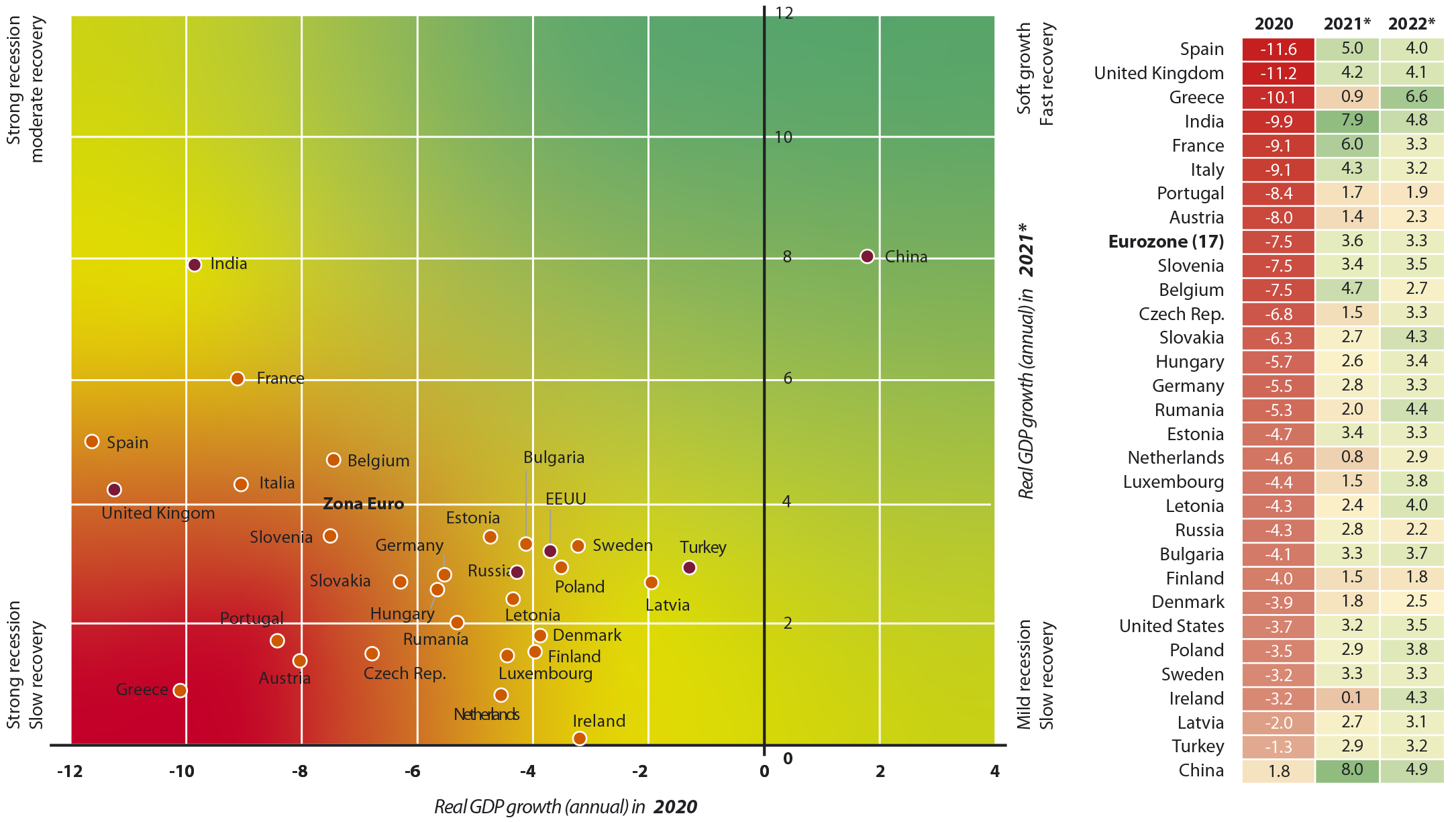

Fall and Expected Economic Recovery (Real GDP Growth, 2020-2021*)

Note: (*) Projection. Source: CIDOB elaboration fom OECD data.

CIDOB Calendar 2021: 100 dates to mark on the international calendar

January 1st - Renewal at the United Nations Security Council. India, Ireland, Kenya, Mexico and Norway will join the UN Security Council as non-permanent members, replacing Belgium, the Dominican Republic, Germany, Indonesia and South Africa.

January 1st - Brexit. The United Kingdom embarks on its solo journey outside the EU after the end of the transition period. The Boris Johnson government faces this phase with a divided UK and unpromising economic prospects due to Brexit and the economic crisis caused by the pandemic. This context will shape the local elections and those to the London Assembly and Welsh and Scottish parliaments on May 6th.

January 5th - Senate elections in Georgia (USA). With no candidate taking 50% in the elections on November 3rd 2020, the citizens of the southern state have another date with the polls early in the year. Either the Republican majority in the upper house will be consolidated or a tie will result, which would give greater importance to Kamala Harris who, as the country’s vice president and Senate president, would have the casting vote.

January 10th - Presidential elections and constitutional reform in Kyrgyzstan. The country has been mired in a major political crisis since the parliamentary elections in October sparked considerable protests that forced their annulment and the resignation of President Jeenbekov. The adoption of a new constitution will also be discussed. National and international human rights organisations question the political balances it would establish between the different state powers.

January 14th - Ten years since Tunisia’s democratic transition began. In 2011, the self-immolation of fruit seller Mohamed Bouazizi prompted protests in Tunisia that led Ben Ali to flee into exile. This is one of a number of dates marking the tenth anniversary of the Arab Spring, a wave of protests with epicentres in Tunisia and Egypt which spread with uneven results across all Arab countries in early 2011.

January 14th - Presidential elections in Uganda. Yoweri Museveni, President of Uganda for almost 35 years, is standing for re-election at a time of high tension in the country. It seems unlikely that the opposition will be able to spring a surprise, but figures like the MP Bobi Wine, who is managing to mobilise younger voters, and Patrick Oboi Amuriat, leader of the main opposition party, the FDC, could cause Museveni trouble.

January 20th - Joe Biden takes over the presidency. The United States enters a new phase with the presidency of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. His announcement of a return to multilateralism and diplomacy has generated some optimism in the part of the international community calling for greater US involvement in issues such as climate change and international trade. The future of Trumpism and its legacy on the national and international stage remains to be seen.

January 22nd - Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). This multilateral treaty signed in 2017 enters into force after over 50 states signed up. Signatories undertake not to participate in nuclear weapons activity, or to develop, test, produce, acquire, possess, store or use them or threaten their use.

February - African Union Summit. The Democratic Republic of the Congo assumes the presidency of the main African body with numerous fronts open on the continent: the economic and health consequences of the pandemic; abuses of governance and democratic backwardness; the socio-economic and governance crisis in Zimbabwe; violent extremism in northern Mozambique; the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam; the crises in Guinea and Mali; and the peace processes in South Sudan and Sudan, among others.

February–March - Palestinian elections. The Palestinian National Authority (PNA) is considering this period for the holding of elections that have been postponed several times since 2014. Symbolically, this is an important year for the PNA, as January 20th will be the 25th anniversary of the election of Yasser Arafat as its first president, a position he held until his death in 2004.

February 5th - The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty expires. Moscow has already announced its willingness to extend New START, the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, which regulates the control of strategic nuclear weapons in Russia and the United States and was signed in 2010 by Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev.

February 7th - Presidential elections in Ecuador. Elections that will take place amid widespread apathy and social discontent following the Lenin Moreno presidency, whose legacy is defined by the deep economic and health crisis plaguing the country. There are three leading presidential candidates: the Correa-approved Andrés Arauz; Guillermo Lasso, a right-wing candidate with the support of the Social Christian Party; and Yaku Pérez, representative of the Pachakutik Plurinational Unity Movement, the political faction of the indigenous movement.

February 8th - Presidential elections in Somalia. An agreement to hold these elections was reached between Somali President Abdullahi Mohamed and key regional leaders. It will be a crucial step in initiating the stabilisation of the country, which has been plagued by a severe political, social and economic crisis for decades, with growing insecurity throughout the territory mainly due to the terrorist activities of Al Shabaab and ISIS.

February 15th - Ten years of the war in Libya. The tenth anniversary of the beginning of the civil war that brought down Muammar Gaddafi’s regime and led to his death on October 20th 2011, in which international involvement was decisive following the adoption of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973. Ten years on, the possibilities of resolving the conflict and the responsibility of regional and global powers will be discussed.

February 18th - Mars 2020 landing. Mars 2020, the most important space mission in recent years is expected to land in the Jezero crater on Mars. The mission aims to spend two years looking for clues of past microbial life.

February 19th–21st - Munich Security Conference #MSC21. Held annually, this is the largest independent forum on international security policies. Bringing together high-level figures from over 70 countries, for 2021 it proposes the concept of a “polypandemic” to discuss the challenges facing the international community.

February 28th - Legislative and municipal elections in El Salvador. The country enters an election year with significant change expected in congress. President Nayib Bukele and his Nuevas Ideas party seem likely to triumph over traditional forces like Arena and FMLN, as well as more recently created ones like GANA. Following a year marked by a clash between executive power and the legislature and judiciary, Bukele hopes to make his high approval ratings and the popularity of his mandate count, the main feature of which has been a notable reduction in rates of violence and crime throughout the country.

March–April - NATO Summit. With Joe Biden assuming the US presidency, the transatlantic ties between the partners, battered by snubs and by Trump, will be restored. The nuclear deal with Iran and the various security challenges affecting NATO will be on the agenda.

March - Presidential elections in Congo. Denis Sassou Nguesso has led the Republic of the Congo for over 35 years, a country with some of Africa’s highest rates of poverty and inequality. There have been protests against Nguesso’s government in recent years which the regime has harshly repressed, prosecuting and imprisoning the main opposition leaders without compunction.

March - Parliamentary elections in Laos. The National Congress of the ruling Lao People's Revolutionary Party early in the year will establish the foundations of its programme and leadership for the parliamentary elections a few months later. Political changes in favour of greater democratic openness are not expected in a country that is highly dependent on China.

March 8th - International Women's Day. Now a key date in many countries’ political and social calendar. Large-scale demonstrations, which have gained momentum in recent years, especially in Latin America and Europe, share a common goal: the fight for women’s rights and gender equality all over the world. The 2021 protests are likely to highlight the increased inequality and gender violence resulting from the pandemic.

March 10th–12th - World Cities Culture Forum. Milan will host this edition of the WCCF, which brings together 38 of the world’s most global cities, and will focus on the pandemic’s impact on cities and their communities, as well as what culture can tells us about the challenges ahead and the lessons for facing them.

March 11th – the WHO and COVID-19. On March 11th 2020, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus announced that the COVID-19 coronavirus epidemic had become a global pandemic. Was this recognition too late? Was there a lack of transparency? The announcement that the Biden administration will again contribute funds to the WHO gives the organisation breathing space, but assessments need to be made on ways to improve health coordination at global level.

March 15th - Ten years since the war in Syria began. The tenth anniversary of the start of a war that has produced the largest international humanitarian crisis in decades, leaving more than half a million dead, 5.6 million refugees and about 6.5 million internally displaced persons. This year Bashar al-Assad celebrates 20 years in power and elections are planned that will be a mere formality designed to buttress the regime, but also a reminder of the failure to draft a new constitution before the presidential election.

March 17th - Parliamentary elections in the Netherlands. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, who leads a four-party coalition, will run for a fourth term, seeking to revalidate and enlarge his majority. The doubt surrounds the level of support the country’s two populist and far-right parties will receive: the Forum for Democracy, whose leader Thierry Baudet recently lost the leadership, and the Party for Freedom, led by Geert Wilders. Rutte gained prominence at European level in 2020 for leading the “frugal four” countries that were reluctant about the EU's pandemic stimulus plans.

March 18th - Fifth anniversary of the Turkey–EU migration agreement. Five years after its implementation, the agreement has clearly reduced the volume of migration along the Turkey–Greece route. This is a good time to discuss the effects of border outsourcing policies on a global scale – with particular focus on the Mediterranean – and on the transactional nature of relations with Turkey.

April 11th - General elections in Peru. The deep political and institutional crisis in which the country is immersed has led it to have four presidents in the past three years; while its last six leaders have all been embroiled in corruption scandals. Peru is also one of the Latin American countries most affected by the pandemic.

April 11th - Elections to Chile's Constituent Assembly. Chile’s political and social crisis erupted when protests broke out in late 2019 and early 2020. The Piñera government was forced to propose a new constitution that includes social rights, new roles for the state and the recognition of indigenous rights to banish the one written during the Pinochet dictatorship. The creation of a Constituent Assembly to draw up the new magna carta offers new hope for social and economic improvement in the country.

April 11th and October 24th - Presidential and parliamentary elections in Chad. President Idriss Déby, in power since 1990, hopes to renew his mandate as a severe crises grips the country. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the refugee crisis on its southern border, Boko Haram's growing activity, the insurgency in the north of the country, and the falling global oil prices that are accelerating the economic crisis are some of the challenges affecting his presidency that he will have to face in 2021.

April 16th–19th – 8th Communist Party of Cuba Congress. It is expected that at the 8th Congress Raúl Castro will hand over the leadership of the PCC to the country’s current president, Miguel Díaz-Canel.

April 21st and 22nd - Ibero-American Summit in Andorra. Andorra will host the main Ibero-American forum, which brings together the heads of state and government of 22 countries. The motto this time is "Innovation for sustainable development - Goal 2030" and the aim is to advance on a joint programme that promotes innovation policies in relation to both the climate change and health crises.

May - Arctic Council. Russia takes over the presidency of the Arctic Council, the main intergovernmental forum for polar cooperation. Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States are the other members. The Arctic Circle is currently a priority strategic area of Russian national interest for reasons both of security and access to natural resources.

May 2nd - Tenth anniversary of Bin Laden's death. Ten years have passed since a US military operation killed Al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan. A fitting moment to take stock of the current state of Al-Qaeda in terms of leadership, presence and strategy, and how jihadist terrorism has been atomised.

May 15th - Tenth anniversary of the indignados (15-M). A protest movement that spread throughout Spain and expressed dissatisfaction with the political system and austerity measures. The movement partially emulated the forms of protest spreading through Arab countries shortly before. In 2021 one of the parties that emerged from this crisis, Podemos, is a minor partner in the first coalition government since the restoration of democracy in Spain.

May 18th–21st - Davos World Economic Forum. Annual event that gathers political leaders, senior executives from the world's largest companies, the heads of international organisations and NGOs, and prominent cultural and social figures. This edition, which will not be held in January as normal, has the slogan "The Great Reset" and will analyse the economic and social recovery of the planet after the COVID-19 pandemic.

May 19th–20th - World Humanitarian Forum. Organised in London, the forum will bring together prominent leaders and international development and global aid agencies, as well as political and business representatives. This edition will focus on new funding models, refugees, climate change and the humanitarian impact post-COVID-19.

May 23rd - Parliamentary elections in Vietnam. At the start of the year, the Communist Party of Vietnam will hold its 13th National Congress, where the new secretary general will be elected, and the country's political priorities will be set. Elections will then be held in late May to fill the so-called “four pillars” of the Vietnamese state for the 2021–2026 period: party secretary general, president, prime minister and chair of the National Assembly. The political agenda in 2021 will look to China. Vietnam's relationship with its northern neighbour is complex and especially strained in the South China Sea.

May 23rd - Parliamentary elections in Cyprus. The Cypriot parliament has 80 seats, but in practice only 56 MPs are elected. The remaining 24 are allocated to the Turkish Cypriot community and have remained vacant since 1964. The two leading parties in Cyprus, DISY – of current President Nikos Anastasiades – and AKEL will compete for a majority in the chamber. The victory of the nationalist candidate in the Northern Cyprus presidential elections and Turkey's policy on Cyprus will condition the electoral agenda, together with the pandemic’s blow to the island's tourism industry.

May 25th - First anniversary of the assassination of George Floyd. His death due to police brutality in Minneapolis provoked civil protests against structural racism that were the largest seen in the United States in decades. President Trump's response further radicalised the protests, which extended across the country for weeks. The trial of the policeman who killed George Floyd begins on March 8th.

May 26th–27th - European Social Economy Summit. Co-organised by the European Commission and the city of Mannheim, this conference aims to strengthen Europe’s social economy and make use of its contribution to economic development, social inclusion and the ecological and digital transitions. Discussions will focus on three dimensions: the digitalisation of the social economy, (social) innovation and collaboration between countries and between sectors.

May 31st–June 4th - EU Green Week. The largest annual event on European environmental policy. Representatives of governments, industry, non-governmental organisations, academia and the media come together for a unique exchange of ideas and good practices. This year it will be dedicated to the “zero pollution ambition”.

June 2nd–4th - General Assembly against Corruption (UNGASS). The United Nations General Assembly in New York will host the first special session to shape the global anti-corruption agenda for the next decade, focussing on the challenges and methods of preventing and combating corruption and strengthening international cooperation.

June 5th - Constitutional referendum in The Gambia. The Gambia’s process of democratic transition is conditional on the holding of a referendum on the approval of a new constitution that would represent a break with the two-decade dictatorship of former President Yahya Jammeh. The new constitution would have introduced significant changes to term limits, female participation quotas, changes to electoral law and greater restrictions on the executive branch, but the proposal was rejected by the current National Assembly. Delays in approving the new constitution would set back the transition and the political and social reforms begun in 2017.

June 6th - Parliamentary elections in Mexico. Two years into the Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) presidency, his party, MORENA, is looking to secure a majority in the Chamber of Deputies and continue the policies that drove AMLO's candidacy. The opposition, especially the traditional parties, PRI, PRD and PAN, will seek to prevent that majority. 2019 has not been a good year for López Obrador, who has watched his security policies fail, leading to historically high insecurity and violence, and shown an inability to cope with the COVID-19 crisis. These elections will also select other federal and local officials.

June 6th - Parliamentary elections in Iraq. The elections scheduled for 2022 were brought forward by six months as a way to reduce social tensions in the country following the massive and continuous anti-government demonstrations of the past two years. The new government will face multiple challenges: the consequences of disastrous pandemic management; pressure from various armed groups (militias); growing insecurity caused by ISIS; an economic crisis due to low oil revenues and exports; and the withdrawal of US troops on the orders of Donald Trump.

June 11th–July 11th - European Championships and Copa America. The world’s top two regional football competitions will be held in parallel for the first time and will also be conditioned by the impact of COVID-19.

June 15th–16th - UN Global Compact Leaders Summit. Brings together over 2,000 leaders from the field of corporate sustainability. It aims to discuss and analyse the role of companies in promoting the SDGs and multilateralism.

June 18th - Presidential election in Iran. The conservatives’ victory in the February 2020 legislative elections has slowed the reformist movements of recent years and boosted expectations that they will also be able to win the country's presidency. Iran's isolation in the regional and international spheres, heightened by the breakdown of the nuclear deal and the hostility of the Trump presidency, has strengthened the country’s conservatives. Joe Biden's victory in the United States opens up the possibility of recovering the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran, one of the last hopes for the reformists.

June 25th - 30th anniversary of the start of the Balkan War. Slovenia's declaration of independence on June 25th 1991 marked the beginning of the disintegration of the former Yugoslavia and the start of a series of armed conflicts that ended in Macedonia in 2001. A good time to analyse the socio-political situation in the Balkans and its framework of relations with the EU.

June 26th – Five years since the FARC announced its ceasefire. Five years have passed since the FARC's historic ceasefire agreement brought an end to 52 years of conflict in Colombia, and led to the signing of the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC on November 24th, 2016.

June 28th - Tenth anniversary of the global eradication of rinderpest. The first successful eradication of an animal disease from the world, achieved thanks to decades of concerted international hard work. Rinderpest had existed for over 3,000 years and cyclically affected societies in Africa, Europe and Asia.

June 28th–July 1st. Mobile World Congress. The world’s largest mobile event brings the main international technology and communication companies to Barcelona. It was one of the first major congresses to be cancelled in February 2020. The offerings in 5G, Big Data and analytics are particularly anticipated at this year’s event. Like any other technological advances presented, they are likely to respond to the changes to individual and business habits that have resulted from the pandemic.

First six months - Global education summit. The governments of the United Kingdom and Kenya are organising a major international education summit to raise funds for the Global Partnership for Education. Its goal is to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on children around the world, millions of whom have been out of school, causing the greatest educational crisis in decades.

First Semester – 47th G7 Summit. The United Kingdom will host the latest G7 summit, which will discuss and seek to reach agreements on some of the world's most pressing issues. Particular emphasis will be given to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic around the world. The United States was due to host the summit in 2020 but postponed it, first because of the pandemic, and then because of the elections. President Trump had raised the possibility of inviting Vladimir Putin.

July 1st - Centenary of the creation of the Chinese Communist Party. A commemoration that takes on global significance due to China’s importance as one of the two great global powers and the persistent discussion over which political and social models respond best to emergencies such as pandemics.

July 6th–15th - UN High-Level Dialogue Forum on Sustainable Development. The central United Nations platform for monitoring and reviewing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals will on this occasion focus on a sustainable and resilient recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

July 6th–7th - The Vienna Energy Forum. Leaders from governments, civil society, international organisations and the private sector gather with the aim of driving the development of inclusive and sustainable solutions around the world. The subject of this year’s event is the Fourth Industrial Revolution, in which avant-garde production techniques are blended with intelligent systems and help catalyse the energy transition.

July 9th – Ten years of an independent South Sudan. The tenth anniversary of South Sudan's independence from its northern neighbour, Sudan, is celebrated. This decade has been characterised by instability, internal tensions and violence, but took a hopeful turn after the peace agreement was reached in 2018 and a government of national unity was formed in 2020.

July 11th - Centenary of the end of the Irish War of Independence. The end of the Irish War of Independence 100 years ago led to the de facto partition of the island between Ireland and Northern Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. This anniversary coincides with Brexit and the controversy about how to manage it within the island, given that introducing physical barriers at the border would go against the terms adopted in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

July 23rd–August 8th - Tokyo Olympics. Japan hosts the 32nd edition of the world's leading sporting event in conditions affected by COVID-19 and its impact on international mobility. The measures Japan adopts may serve as an example for other major international events.

August - Pacific Islands Leaders Forum. The main pan-regional discussion forum in Oceania brings together the interests of 18 states and territories on issues such as climate change, the sustainable use of maritime resources, and regional cooperation. One of the group’s goals is to attract the United States and European and Asian partners to the organisation’s shared interests, especially the fight against climate change.

August 12th - Presidential and parliamentary elections in Zambia. The first African country to default in the midst of a pandemic, aggravating its already-severe economic and social crisis. These are the circumstances in which Hakainde Hichilema’s opposition seeks to win the elections and then redirect Zambia’s economic policy. Internal tensions have already broken out, fuelling international concern over the fairness of the elections.

August 31st - First anniversary of the Sudanese peace agreement. After 17 years of civil war, the Sudanese government and five rebel movements grouped in the Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF) signed a historic peace agreement in 2020 that ended a conflict that had claimed the lives of at least 300,000 people and internally displaced millions. This will be an opportunity to analyse the progress of the peace agreement and the changes that have taken place in the country, especially in the regions most affected by the conflict, Darfur and the Blue Nile.

September - UN Food Systems Summit. The United Nations Secretary-General has promoted this international summit where new lines of work and public policy will be presented to improve global food systems by making them healthier, more sustainable and fairer, and thereby promote public debate about them throughout the world.

September - Parliamentary elections in Russia. Surprisingly good results for the opposition in the last regional and local elections raise the pressure on Vladimir Putin, who will try to prevent them entering the Duma as well. The atmosphere of social discontent about the economic crisis and the impact of the pandemic could mean some candidates successfully secure nomination and achieve enough support.