China in the heart of Eurasia

Lying halfway between China and the markets of the Middle East and Europe, Central Asia is a key component of Beijing’s Eurasian interconnection drive. Its geographical location, and its natural resources, make the region an invaluable partner for China, which also views some countries of the region as vital to its security. However, China’s growing presence in Central Asia has brought with it a rise in Sinophobia among the local population.

On 18 May 2023, President Xi Jinping hosted the leaders of the republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan in the city of Xi’an. It was the first China-Central Asia summit between the heads of state of these six countries. In the three decades since gaining independence after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the five Central Asian states have become a centrepiece of China’s foreign policy. Faced with the risk of being treated as single bloc, each of these republics has its own policy towards China, and vice versa.

Central Asia has turned into one of China’s main providers of natural gas over the last two decades, while Beijing has invested billions of dollars in infrastructure projects to make the region a pivot of its geopolitical aspirations. In addition, there are growing political ties between the Central Asian capitals and Beijing, as could be seen in Xi’an. But China’s presence in Central Asia has brought with it a rise in Sinophobia in the region and there are concerns about some Central Asian countries’ disturbing levels of debt with Beijing.

Beyond the “Belt and Road”

Beijing had been eyeing Central Asia for some time before terms such as “Belt and Road Initiative” appeared in official speeches in 2013. It had also sunk billions of dollars into infrastructure projects in the region, a figure that hit $68bn in 2022. Access to hydrocarbons and overland connections to facilitate China’s entry into third markets have dominated Sino-Central Asian relations for years.

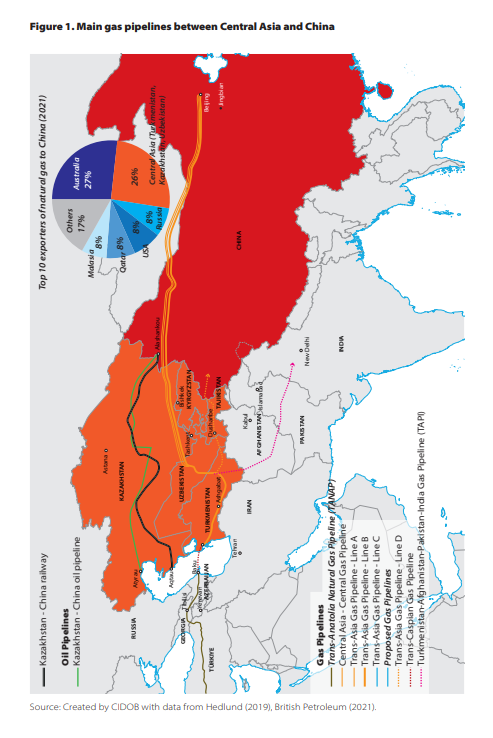

In the 2000s, with China seeking sources of energy to sustain its economic growth and Central Asia ready to diversify its exports, came the Central Asia-China gas pipeline. It is the primary gas infrastructure in the region and one of the most important in Asia. This pipeline system transports mainly Turkmen, as well as Uzbek and Kazakh, natural gas that together accounts for 26% of China’s gas imports. Since it entered operation in 2009 it has become China’s main conveyor of pipeline-imported natural gas, ahead of Russia. It is hardly surprising, then, that between 2007 and 2014 China bankrolled the construction of its three lines through the state-owned oil company China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and loans from the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Bank of China.

As well as natural gas, China imports oil through the Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline, with a capacity of up to 20m tonnes of crude a year, albeit a token amount considering China’s total oil imports.

For China, the region is largely a captive supplier with limited manoeuvrability in the negotiations around natural gas supply. The economy of its main provider, Turkmenistan, relies on exporting natural gas to the Asian giant. Moreover, it was not until 2021 that Beijing began to pay Ashgabat full price for the gas, after the debt for the construction of the Turkmen section of the pipeline and other gas projects had been settled through natural gas exports. China could boost its supply thanks to a fourth line of the Central Asia-China gas pipeline system, which would significantly increase the region’s export capacity. However, this decision to build Line D will depend on Beijing’s appetite for energy.

Another of China’s ambitions for Central Asia is to make the region a hub in the transport of goods to markets in the West. Beijing has enjoyed less success in this regard. Projects such as the Khorgos dry port between China and Kazakhstan, the “new Dubai” as the South China Morning Post once dubbed it, have not matched expectations. Transporting goods across Eurasia is largely unprofitable without subsidies. The war in Ukraine and the interest in the West Asia Corridor of the Silk Road Economic Belt, a route that connects China with Iran and Turkey skirting Russia, could change things in the future. In fact, there are already routes across the region linking China with Ankara, but so far, they have not proven as popular as hoped.

Following hectic construction activity in the early 21st century, there are few key infrastructure projects for China remaining in the region. Before Xi Jinping announced the “Silk Road Economic Belt”, the overland route of the BRI, on a visit to Astana in 2013, some of the main undertakings, such as the Central Asia-China gas pipeline, the Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline or the modernisation of the Atyrau refinery in Kazakhstan, were already up and running. While positive investment in the region will continue, especially in the extractive, industrial and transit sectors, only two major projects have still to be developed: Line D of the Central Asia-gas pipeline and the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway. This will shape China’s relations with the region into the future. In any case, the age of mammoth Chinese infrastructure projects is over.

Despite the drop in investment, China continues to consolidate its trade position and has dislodged Russia as the main trading partner of the five countries. Central Asian markets have seen a considerable rise in Chinese consumer goods over the last few years, from textiles to electric cars, and this trend is expected to continue. It is not a major market compared to other regions of the world, but Central Asia’s little over 80m consumers are just across the border.

A Debt trap?

Chinese investment in the region over the last few years can be seen as a double-edged sword, particularly for Central Asia’s two smallest economies: Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Lacking the natural resources or demographic weight of their Central Asian neighbours, both countries rely heavily on loans from foreign lenders to undertake major infrastructure projects. China and its Export-Import Bank of China (Eximbank) are the chief international creditors of both Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, accounting for 52% of Tajiki foreign debt and 45% of Kyrgyz external borrowing. This is equivalent to over 20% of their respective GDPs. The economic situation, particularly in Tajikistan, hardly buoyant already and affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, could make it harder to service that debt.

Opinion is divided over whether this is a deliberate strategy on the part of Beijing, a component of a so-called “debt trap”. But this asymmetry and dependence gives China a significant edge in its bilateral relations with the two countries. This translates into amenability on matters such as granting mining concessions or, in the case of Tajikistan, tightening security ties, a particularly significant point in a regime with the transparency and corruption issues of Dushanbe. While Tajikistan’s cession of over 1,300 sq. km of its territory to China in 2011 was not related to debt payments but to a renegotiation of a border dispute, it still sets a disturbing precedent for the future. And it is all the more important given China’s irredentist narratives, echoed in the national press, claiming the Pamir region of Tajikistan as its own. Nevertheless, it is also possible that for the sake of maintaining good relations with the two countries Beijing will agree to refinance or even cancel part of the debt. Tajikistan can access Central Bank of China emergency liquidity lines equivalent to 5% of its economic output and yet, significantly, it has done so only once (in 2015) to keep the local currency afloat, for a limited amount of $500 million.

Tajikistan as a buffer

Tajikistan plays an important role in China’s security strategy precisely because of its frontier geographical position in the Pamir Mountains. Lying in the south-eastern corner of the region, Tajikistan shares a border with China of a little less than 500km. More importantly, it shares one with Afghanistan running for over 1,350km. China’s priority is not so much to expand its military presence in the region as a projection of its power but to shield itself from threats that could come from abroad, in this case from Afghanistan via Tajikistan.

This prompted Beijing to secure an outpost for some 100 members of the People's Armed Police (PAP) in the far southeast of Tajikistan, in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO). In addition, in 2021 the Tajiki government announced the construction of another outpost in western GBAO, near the border with Afghanistan. Officially, China is funding the $10m cost of building the facility even though it will supposedly house Tajiki special forces.

For the same reason, China has staged primarily bilateral counterterrorist manoeuvres with Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and, particularly, Tajikistan over the last few years. All this is driven by its goal of protecting itself from unconventional threats that could penetrate China via its Central Asian neighbours. To a lesser extent, Beijing has also become a weapons supplier to the region, providing some of its armed forces with equipment such as drones, vehicles and even antiaircraft missiles.

The Sinophobia issue

China may have invested huge amounts of funds in Central Asia, but a large part of the region’s society still eyes the Asian giant with suspicion. According to surveys conducted by the Central Asia Barometer between 2017 and 2021, the opinion of Kazakhs, Uzbeks and Kyrgyz people regarding China has deteriorated over time. There are several reasons for this.

While China has ploughed substantial sums of money into Central Asia, the citizens of the region do not get the feeling they have benefited from it. In some cases, it is down to the dubious quality of the infrastructure projects executed by China, like the Bishkek thermal power plant. Following modernisation by a Chinese company, it broke down in the winter of 2018. Another gripe is the way in which the China-funded work is executed. Chinese contractors are hired and workers brought in from China, meaning most of the profits never reach the locals. In addition, there is friction and conflict between the local populations and the foreign workers that sometimes ends in violence.

Another factor is the fear that China will snatch their natural resources or territory. The clearest example of this came in Kazakhstan in 2016, when the Central Asian country witnessed its biggest protests since independence, against a law allowing foreign nationals to lease land for 25 years. The demonstrations took on an anti-Chinese bent, and the Kazakh government was forced to backpedal. Similarly, there is a distrust of Chinese extractive companies. In nationalist circles in particular, they are considered a threat to sovereignty.

To a lesser extent, there is the Chinese regime’s repression of Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other Turkic minorities in the region of Xinjiang. Most of Central Asian society takes no stand on the issue and its governments comply with Beijing’s requests for non-interference on its internal affairs, including the Uyghur situation. In Kazakhstan, however, members of the Kazakh community who emigrated from China have indeed raised their voices, making things awkward for the authorities. All this serves to tarnish China’s image in the eyes of Central Asians. However, as far as government relations are concerned, however, the ties between the region and China are unaffected.

On a historical, cultural and social level, China does not carry much weight in Central Asia and despite a growing use of soft power, especially in education and universities, it still has a limited presence in those areas. Nevertheless, the recent summit in Xi’an made it clear that relations between the region and Beijing will continue to grow stronger on every level. The age of huge infrastructure projects may be at an end, but political, trade and security ties will continue to tighten in the future, as demonstrated by the joint declaration signed by the presidents of the six countries in Xi’an. Central Asia will remain a key partner because of its resources and geographical location. For the Central Asian republics, meanwhile, Beijing will continue to provide an alternative with which to balance a foreign policy largely bound to Russia. And, depending on the country, it will continue to be an important export destination and source of investment.

Bibliography

Aminjonov, Farkhod and Dovgalyuk, Olesya. “Central Asia–China Gas Pipeline (Line A, Line B, and Line C)”, The People’s Map of Global China (February 2023) (online) [Retrieved 9 May 2023] https://thepeoplesmap.net/project/central-asia-china-gas-pipeline-line-a-line-b-and-line-c/

Baker, Thomas and Woods, Elizabeth. “Public Opinion on China Waning in Central Asia”, The Diplomat (May 2022) (online) [Retrieved 10 May 2023] https://thediplomat.com/2022/05/public-opinion-on-china-waning-in-central-asia/

Olmos, Francisco. “Pleasing China, appeasing at home: Central Asia and the Xinjiang camps”, The Foreign Policy Centre (November 2019) (online) [Retrieved 12 May 2023] https://fpc.org.uk/pleasing-china-appeasing-at-home-central-asia-and-the-xinjiang-camps/

Olmos, Francisco. “Seguridad en Asia Central: China aumenta su peso en Tayikistán”, GEOPOL 21 (December 2021) (online) [Retrieved 10 May 2023] https://geopol21.com/seguridad-en-asia-central-china-aumenta-su-peso-en-tayikistan/

South China Morning Post. “Khorgos: the biggest dry port in the world” (online) [Retrieved 11 May 2023] https://multimedia.scmp.com/news/china/article/One-Belt-One-Road/khorgos.html

Umarov, Temur. “China Looms Large in Central Asia”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (March 2020) (online) [Retrieved 11 May 2023] https://carnegiemoscow.org/commentary/81402